The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources says roughly 800 public water systems tested are meeting the state’s drinking water standards for PFAS, according to preliminary sampling results.

Even so, environmental advocates caution that 4 percent of those water supplies had levels of the so-called forever chemicals that go beyond the Environmental Protection Agency’s proposed drinking water standards.

Wisconsin’s drinking water standard of 70 parts per trillion went into effect last August for two of the most widely studied PFAS chemicals: PFOA and PFOS. Since then, the EPA proposed standards of 4 parts per trillion for the two substances earlier this year. That’s about 17 times more stringent than the state’s current threshold.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

About 800 public water supplies have collected more than 1,500 samples testing for PFAS, according to Kyle Burton, the agency’s field operations director with the drinking water and groundwater program. Burton said no systems exceeded state standards, and nearly 63 percent of samples detected no trace of the chemicals.

“It’s a positive to see that there is a significant majority of the systems that we’re getting sampling results from that are not negatively impacted,” Burton said. “But we still have a lot of data to collect.”

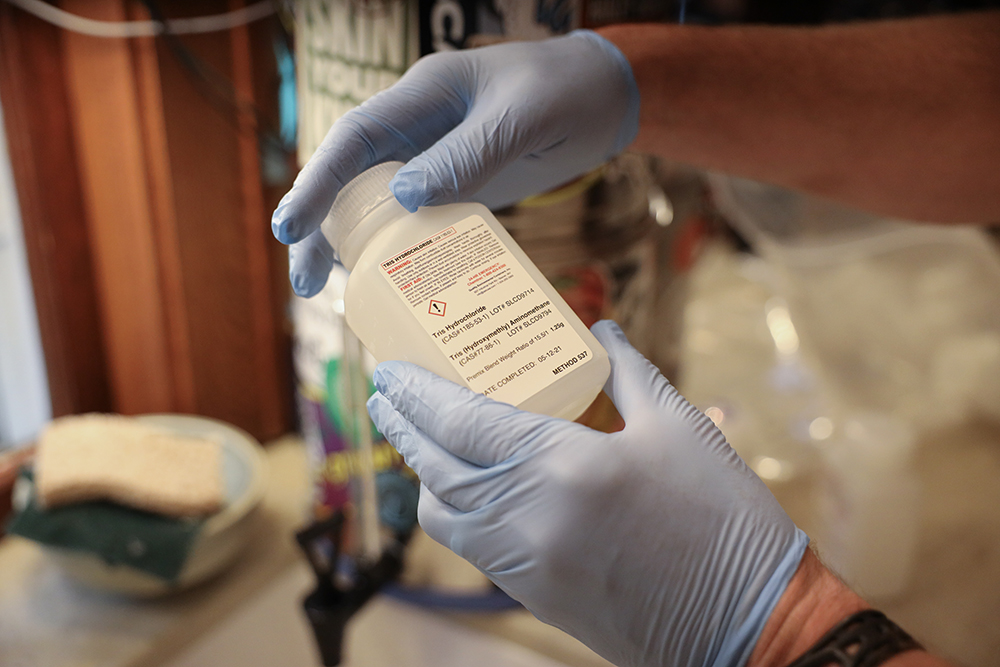

PFAS, short for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are a class of thousands of synthetic chemicals used in products like cookware, food wrappers and firefighting foam. Research shows high exposure to PFAS has been linked to kidney and testicular cancers, fertility issues, thyroid disease and reduced response to vaccines over time.

Burton said about 1.4 percent of samples went beyond proposed groundwater standards of 20 parts per trillion that have been recommended by the state Department of Health Services. The Natural Resources Board failed to pass limits for the chemicals in groundwater last year. Since then, the DNR has restarted the process for crafting those regulations, which would set standards for about a third of state residents who rely on private wells.

Around 2,000 public water systems that serve communities, schools and businesses are now required to regularly test for PFOA and PFOS. The DNR has taken a phased approach for systems that are required to conduct monitoring, which began with water supplies serving 50,000 people or more. All systems will collect their first samples by late this year, and the state’s more than 600 municipal water supplies have already tested for the chemicals.

Environmental advocates say the state’s PFAS standards and sampling requirements have been vital for assessing the scope of contamination, according to Sara Walling, water and agriculture program director for Clean Wisconsin. While early results show all systems tested are meeting state standards, Walling said it paints “too rosy of a picture” given that the EPA is proposing stricter limits for PFAS in drinking water.

An analysis by the group that was verified by Wisconsin Public Radio shows at least 32 public water supplies had levels of the chemicals that went beyond standards proposed by federal regulators. Walling said that’s roughly 4 percent of the nearly 800 systems tested to date.

“It’s great to see that, overall, the contamination problem so far from our data isn’t as widespread as we may have anticipated,” Walling said. “But to those that are impacted, that doesn’t provide a lot of satisfaction.”

Walling said those systems may need to install additional treatment to bring levels in line with the EPA’s proposed standards if they’re approved.

The DNR is still gathering data for review in relation to the EPA’s suggested limits for the chemicals. Burton said they plan to communicate with water systems that may exceed those standards once federal regulators issue a final rule. The EPA aims to issue a final proposal by the end of this year or early next.

Lawrie Kobza, legal counsel for the Municipal Environmental Group-Water Division, said in an email that testing will help state water supplies be prepared once those standards are finalized.

“Based on testing so far, it appears that most municipal water systems will be able to meet the proposed federal PFAS standards,” Kobza said.

The Wisconsin Rural Water Association represents the state’s small rural water utilities. Chris Groh, the group’s executive director, said they hope the EPA will enact reasonable standards for treating the chemicals.

“I think they can reach compliance. It’s just going to be at a cost, and is that cost going to ruin the town?” Groh said. “Is it going to bankrupt the town or cause rates to increase so high that people move?”

Water and industry groups have highlighted concerns over the cost of complying with more stringent standards. The American Water Works Association estimates treatment of PFAS in drinking water could cost up to $38 billion nationwide. In small communities, Groh has said the cost to replace a contaminated well may run up to $2 million.

Walling said it’s important to identify the source of the chemicals and take steps to prevent them from entering drinking water to help keep costs down for water supplies. She said that includes removing PFAS chemicals that aren’t essential for certain products or manufacturing.

The DNR’s Burton said sampling has uncovered new PFAS detections in some communities statewide, and those results are available on the agency’s website. He said no new municipalities have requested bottled water from the agency, and affected communities have been taking steps to reduce exposure to the chemicals. Those steps have included blending contaminated water with unaffected wells, taking affected wells offline or installing temporary treatment systems.

The 2023-25 state budget includes $125 million to address PFAS contamination statewide. Republican lawmakers have authored a bill on how that money would be spent to help communities address the chemicals. The proposal is still making its way through the legislative process, although environmental groups and residents are voicing concerns about industry-supported provisions that would weaken the DNR’s authority to address the chemicals.

Even so, Walling said she’s optimistic.

“Lawmakers are recognizing this as a really significant problem,” she said. “And they’re willing to do what they can to try to provide some relief, if not, remedy the situation.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.