Wisconsin Republicans released a plan that would change the way most public schools in the state teach children to read.

State Rep. Joel Kitchens, R-Sturgeon Bay, and State Sen. Duey Stroebel, R-Cedarburg, held a press conference Thursday in Madison discussing the bill that will move schools away from teaching what is known as “balanced literacy” to a “science of reading” approach.

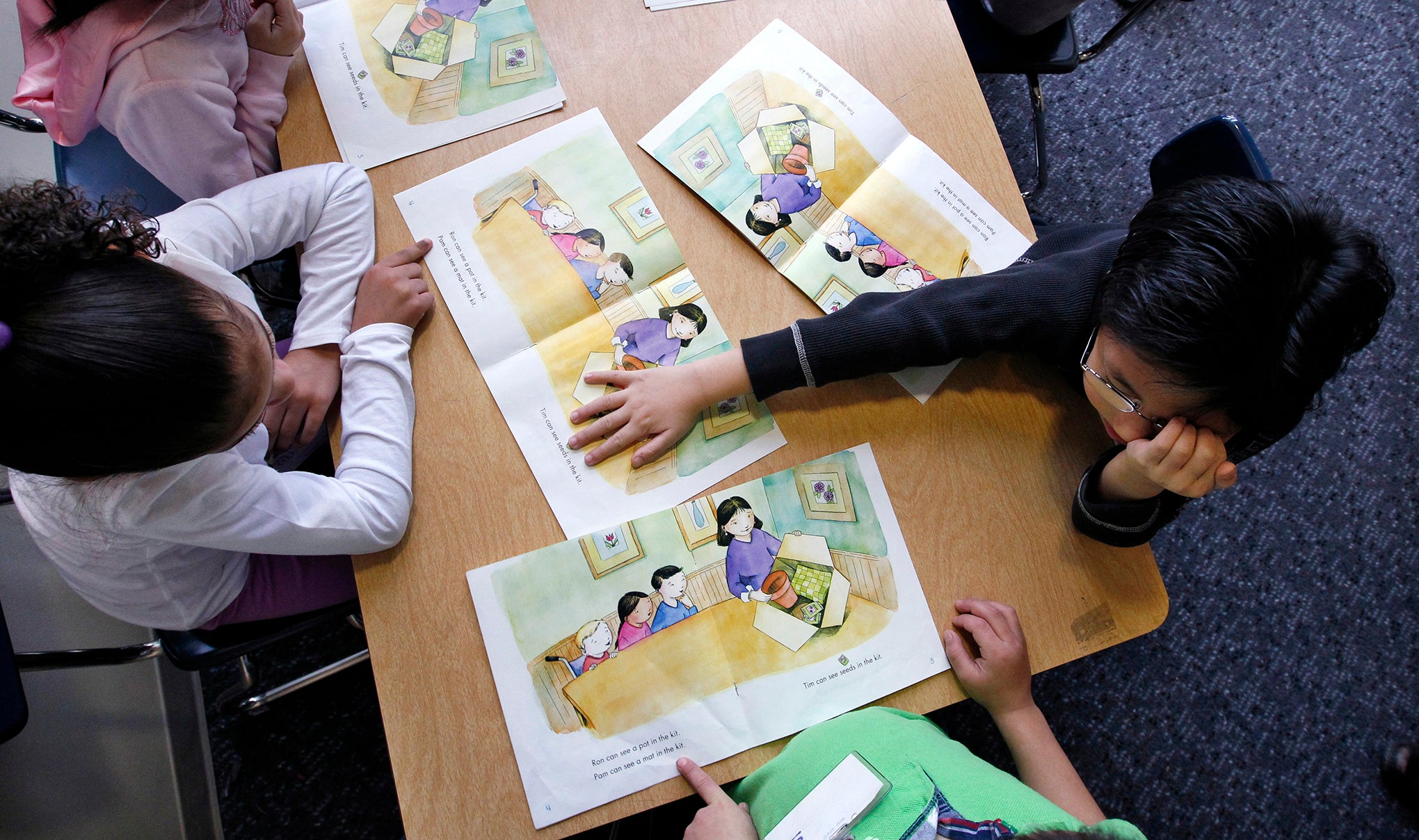

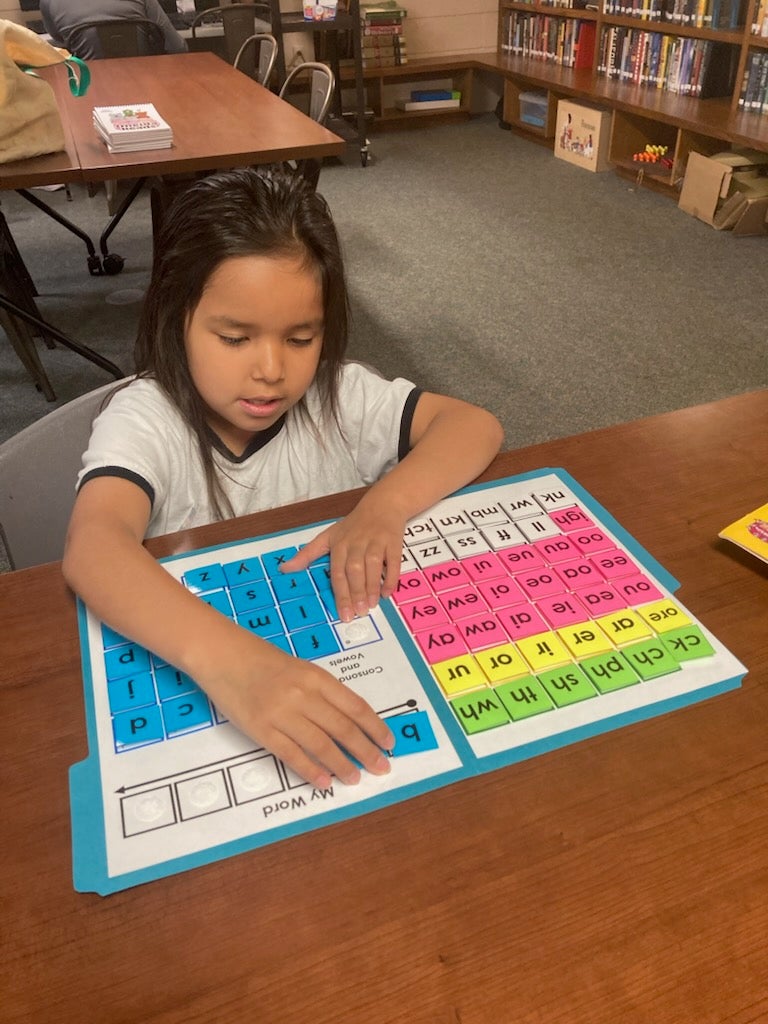

Instead of being taught reading through pictures, word cues and memorization, children would be taught using a phonics-based method that focuses on learning to sound out letters and phrases.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

According to DPI, only about 20 percent of school districts are using a phonics-based approach to literacy education. Other reading curriculums that don’t include phonics have been shown to be less effective for students.

The bill will include $50 million in the state budget — up from $15 million — that would be used to retrain teachers, hire reading coaches and purchase curriculum materials. That money would be in addition to a $1 billion investment in K-12 education funding announced Thursday as part of a shared revenue agreement.

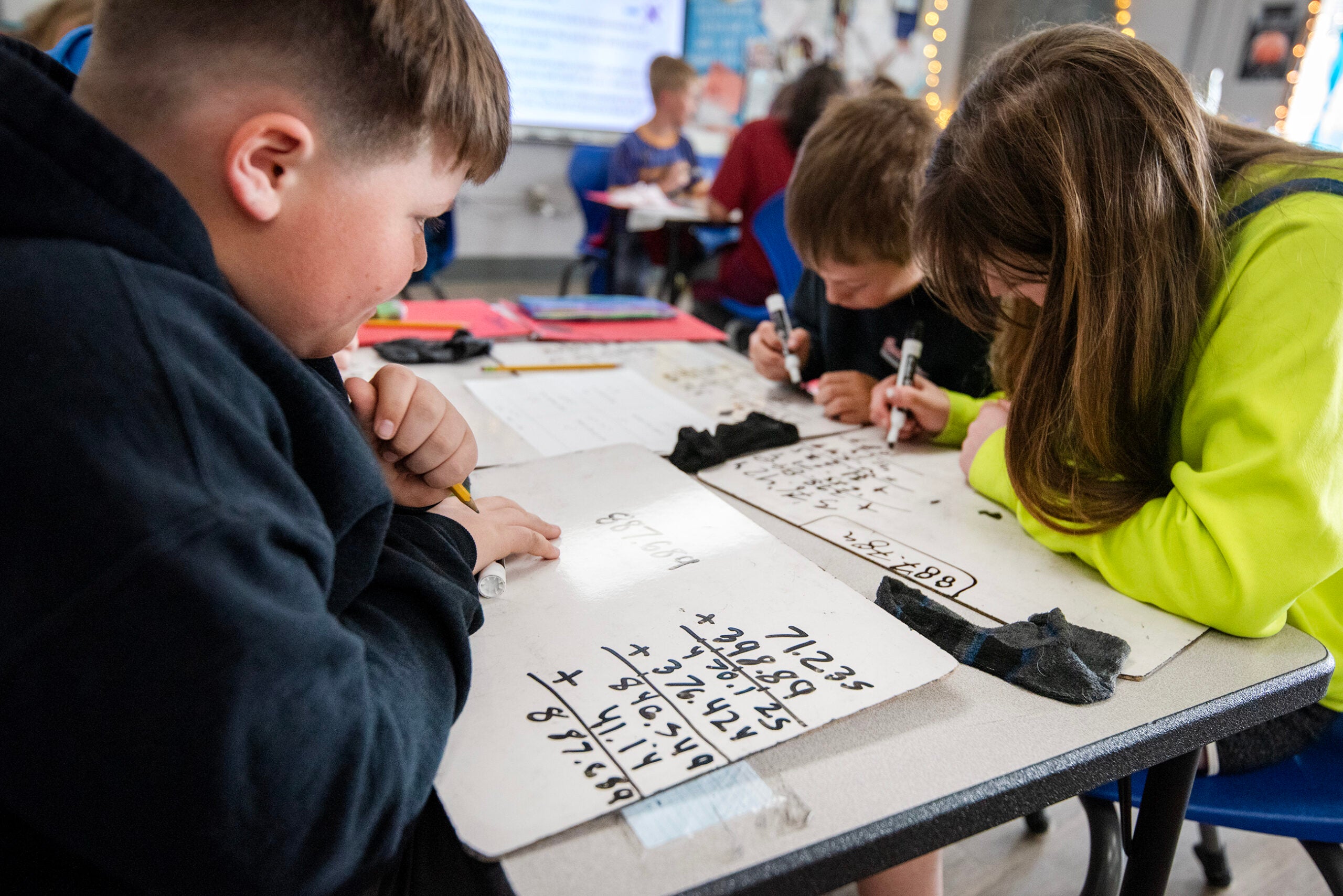

“Wisconsin currently faces a literacy crisis,” Stroebel said, “In 2022, nearly 70 percent of Wisconsin fourth graders were not reading at grade level. This is the lowest recorded score since 1998. Further, students are four times more likely to not graduate if they aren’t reading at grade level by third grade. This bill will get Wisconsin back on track to close achievement gaps in reading and language arts by shifting to a science of reading approach.”

Republicans have modeled their plan off Mississippi, which is often cited by advocates of the science of reading curriculum. From 2013 to 2019, Mississippi fourth graders increased their reading scores on a national exam by 10 points after the state transformed its approach to reading instruction.

“Mississippi is sort of the poster child in having gone from dead last in the country to essentially being tied with us,” Kitchens said.

The bill will also include requirements for screening beginning in kindergarten to identify students who need extra help.

“These are not standardized tests, these are quick screenings that take maybe 15 minutes. And then in first, second and third grade, it will be three times a year,” Kitchens said. “What we do with that is we identify kids who are struggling, and we’ll do diagnostic testing, and they’ll be put on a plan to catch them back up.”

DPI says third-grade retention policy is a ‘non-starter’

State Superintendent Jill Underly released a statement saying she does not support the plan as it stands, despite working with key legislators on it for more than four months, because of the retention policy requirement.

“That is a non-starter for us because, as drafted, it is harmful to our learners, families and communities,” Underly said. “My staff will be able to respond with further information as soon as we have had time to thoroughly read the current bill, which differs considerably from versions we had previously seen.”

Under the bill, by Jan. 1, 2025, the Department of Public Instruction must establish a model policy for promoting third-graders to the fourth grade. The policy must include that students who score in the lowest proficiency category on the third grade reading assessment be retained in the third grade. There is also a requirement that school boards provide “intensive instructional services, progress monitoring, and supports to a pupil who is retained under the policy.”

Additionally, beginning on Sept. 1, 2028, school boards, independent charter schools and private schools participating in a parental choice program are prohibited from promoting a third grade student unless the child complies with their respective promotion policy.

“There will be a lot of interventions. We don’t want to hold kids back,” Kitchens said. “If we’re catching them early … and they’ll have a lot of opportunities to take the (standardized) test. That’s the last resort.”

More than 30 states have already adopted laws or are moving toward requiring school districts to use a science of reading approach. But partisan gridlock in Wisconsin has kept the state from moving forward on a comprehensive reading plan for several years, despite third grade reading test scores remaining stagnant or falling.

Only 33.8 percent of third-graders were proficient in reading on the most recent Wisconsin Forward Exam. Wisconsin’s achievement gap between Black and white fourth grade students in reading has often been the worst in the nation.

Previous reading-related bills brought forward by the GOP have been vetoed by Democratic Gov. Tony Evers. They included a 2021 bill that would have increased the number of times students were tested and asked schools to come up with intervention plans for students who scored poorly.

Evers also vetoed a similar 2022 bill. With both vetoes, the governor raised concerns about retention and long-term sustainable funding.

Editor’s note: this story has been updated to include that funding for the program would be in addition to a $1 billion investment in K-12 education funding announced Thursday as part of a shared revenue agreement.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.