This story was produced as part of a collaboration with the Center for Public Integrity and USA TODAY.

The 2017-18 school year was difficult at Lakeland Union High School. Disciplinary problems came in waves for the Oneida County school — in February 2018, two students were arrested for making terror threats — just days after the mass shooting at Florida’s Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School.

“That was a rough year,” said Chad Gauerke, the school principal. Lakeland referred over 6 percent of its students to police, including the two teenagers, whose separate threats shut down the school for a day.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

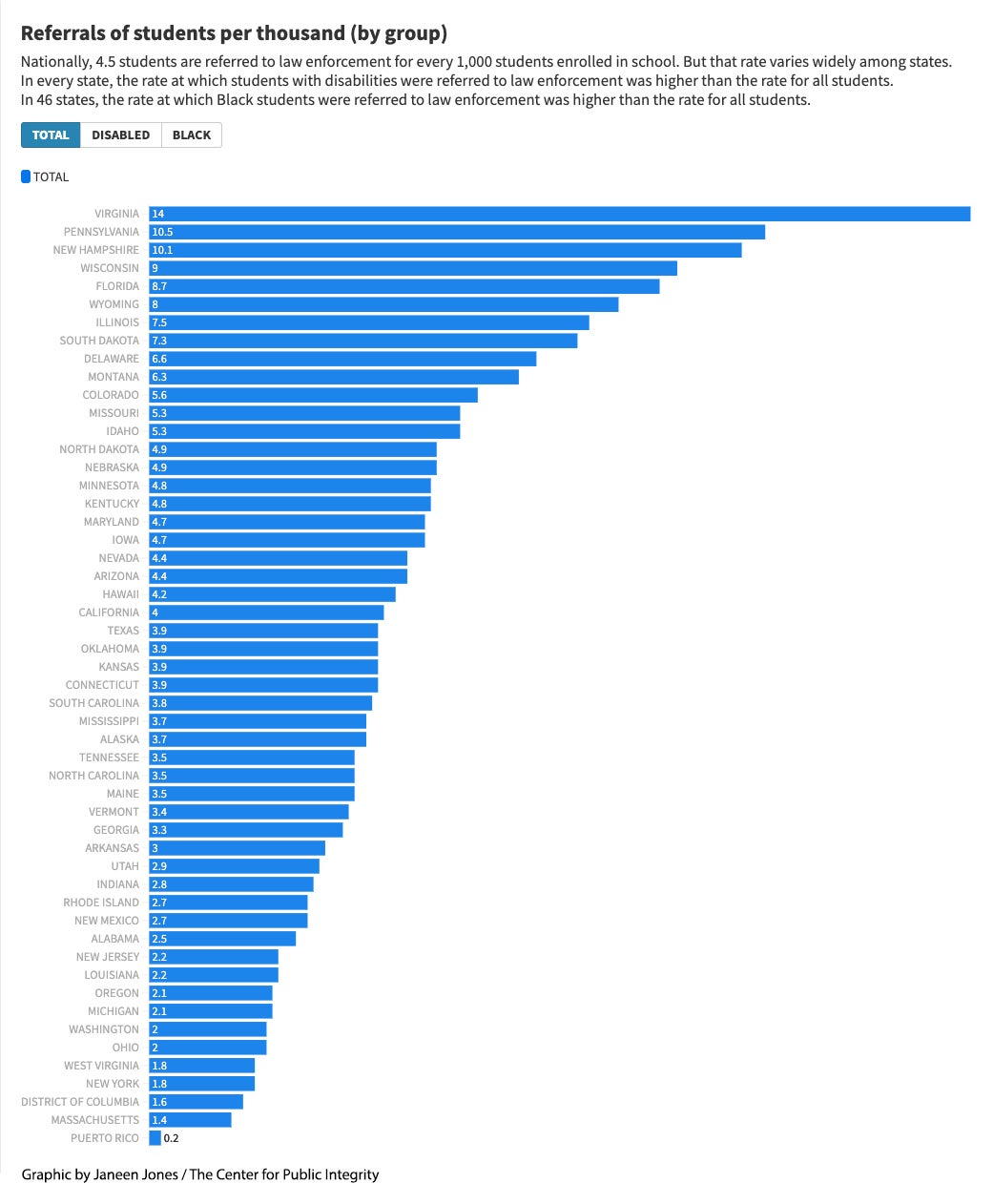

Lakeland wasn’t the only Wisconsin district that saw a high level of police involvement that school year. Public schools in Wisconsin referred students to police twice as often as schools nationwide in 2017-18 — nine students were referred to police for every 1,000 students enrolled compared to the national rate of 4.5, a Center for Public Integrity analysis of U.S. Department of Education data found.

Just three states — New Hampshire, Pennsylvania and Virginia — reported higher rates of referral than Wisconsin.

The analysis of data from all 50 states plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico found that school policing disproportionately affects students with disabilities, Black children and, in some states, Native American and Latino children. Nationwide, Black students and students with disabilities were referred to law enforcement at nearly twice their share of the overall student population.

In Wisconsin, students with disabilities and students of color also bore the brunt of school policing. In 2017-18, Wisconsin was more likely than any other state to refer Native students to law enforcement, reporting a rate over three times higher than the rate of referral for their white peers.

Diana Cournoyer, the executive director of the National Indian Education Association, called the numbers “appalling” and “disturbing.” But, she said, “I’m not surprised. Every Native person knows this, whether you’re in Wisconsin or not.”

That school year, Lakeland was at the top of the list in Wisconsin for referring Native students, and near the top of the list for referring students overall. In addition to the threats, Lakeland students were referred to police in 2017-18 for possessing drugs, alcohol and tobacco, Gauerke said.

Levi Massey, Lakeland’s assistant principal, said the district recognizes the disparity and is working to reverse it with “a school culture that creates a greater acceptance for all our students.”

Lakeland, he explained, is collaborating with a top University of Wisconsin-Madison researcher on “culturally responsive interventions” to reduce the school’s disciplinary issues, especially among Native students.

A key element is strengthening the relationship between Lakeland and the Lac du Flambeau reservation, where up to a third of Lakeland students live.

Massey said there has long been a rift between the tribe and the school district, a remnant of the days when Native children were removed from their homes and sent to government-funded boarding schools. At schools across Wisconsin, including one housing Lac du Flambeau members, children were stripped of their language and culture to be assimilated into the white-dominated culture. An immersion school in northern Wisconsin seeks to restore the Ojibwe language and culture lost over the generations.

Today, Massey said, “Our goal is to create a presence for our school district in the tribal community, so they can see that we’re all working together to do our best for the students.”

The project, which is in its third year, aims to address disparities across the board. “Lowering referrals,” Massey said, “would be a secondary effect.”

‘Racism And Racial Disparities Continue’

In the 2017-18 school year, the most recent year data are available, the school districts reporting the highest rates of referral were Webster, White Lake, Unity and Lakeland. Lakeland, Webster and Unity also reported high rates of referring Native students, as did the Seymour Community District.

Black students, whose rate of referral in Wisconsin is only slightly below that of Native students, were referred most often in the Sparta Area School District, followed by Sheboygan Falls and Portage Community. (Schools referring fewer than five students in any category were excluded from the analysis.)

As for students with disabilities, White Lake reported the highest rate of referral, followed by the Webster, Rhinelander and the Dodgeville school districts.

Milwaukee’s rate of 7.2 per 1,000 students referred to police was below Wisconsin’s overall referral rate of 9 but higher than the national rate of 4.5. Likewise, Madison’s reported 6.2 students referred per 1,000 was also higher than the national rate.

The Stoughton School District ranked in the top 10 when it came to referring Black students and those with disabilities to the police. Stoughton school spokesperson Molly Shea wrote in an email that the district “has come a long way as a community” through “thoughtful work in the past several years to promote all types of equity, including racial justice.”

But, Shea added, “these instances deeply trouble us. Racism and racial disparities continue to be a problem in our schools and in our community.”

‘Criminalizing’ Bad Behavior

The repercussions ripple through communities in urban, suburban and rural areas alike. In 31 states as well as D.C., Black students were referred to law enforcement at more than twice the rate of white students, the Center for Public Integrity analysis found.

These sharp disparities come despite years of mounting pressure on schools to stop policing kids.

“They’re criminalizing some ordinary behavior of students and they’re certainly disproportionately referring students of color to the juvenile justice system rather than disciplining them at school,” said Maura McInerney, legal director at the Education Law Center, a Pennsylvania legal advocacy group.

In 2017, a national study at the University of California-Irvine found that on-campus arrest rates for children younger than 15 increased in areas where the federal government made grant money available in 1999 for school resource officers — a response to the mass shooting at Columbine High School. The funding was available whether a district struggled with crime or not, which helped researchers tease out the impact.

Nationwide, roughly a quarter of law enforcement referrals lead to arrests, federal data show. But students who aren’t arrested may still be issued citations that require them to appear before judges or other juvenile court system officials. The federal data do not specify what the referral was for, nor the result.

The data also showed students with disabilities are among those more likely to be referred to the police.

“These are kids that school districts have traditionally not done a good job of helping,” said Diane Smith Howard, managing attorney for criminal and juvenile justice for the National Disability Rights Network. “They don’t do a good job, the kids act out and then instead of fixing the problem, they call the police.”

Data, Approach Can Be Inconsistent

However, some Wisconsin educators cautioned that the data can be misleading. Reporting standards and annual rates can vary widely by district and by year.

The definition of a law enforcement referral is “really wide open,” said Nathan Hanson, district administrator of the White Lake School District in Langlade County. “It’s kind of up to school districts to figure it out.”

Brandon Robinson, district administrator of the Unity School District in Polk County, agreed. He said that the data from Unity was “inflated” due to the district’s broad interpretation of “law enforcement referral.” In Unity, the term also covers outreach to county social services. The “referral,” Robinson wrote in an email, could simply represent “a conversation with a juvenile justice case worker,” or referral for a student in crisis.

Hanson, who has worked in four different school districts and was responsible for reporting data in one, also noted that different counties can take different approaches to the same disciplinary problems. In some, truancy is reported to social services. In others, the police department is notified.

“When I talked to people around here, it wasn’t uncommon (in 2017-18) to give a police referral for swearing at a teacher — things that are disorderly conduct,” Hanson said. “But now we’d look at handling that in house.”

One academic year also provides a small sample size. Hanson said in small districts like White Lake, rates can fluctuate significantly from year to year. In 2020-21, for example, White Lake reported zero referrals, he said.

Decades Of Policing Students

The roots of school policing reach back to 1948, when Los Angeles formed a security unit that grew into a full-fledged school-based law enforcement agency. In the 1950s Flint, Michigan posted officers borrowed from city ranks in schools to serve as “liaisons” in an anti-crime strategy. School shootings, including the 1999 Columbine massacre, led to an expansion of this policing. “Zero tolerance” for weapons morphed into crackdowns on kids’ behavior.

Between 2006 and 2018, the share of schools reporting the presence of one or more security officers on-site at least once a week grew from 42 percent to 61 percent. The higher the enrollment and proportion of children eligible for free or reduced-price school lunches, the more likely schools are to have security, according to a 2020 report from the U.S. departments of Education and Justice.

Federal funds remain available to schools that want to hire police. And because of the specter of school shootings, many parents, staff and children like to know an armed officer is on site.

The UC-Irvine study found that principals in schools with more officers reported lower rates of criminal incidents. But with that decline came an increased likelihood that children accused of disruptive behavior would come into contact with someone in the criminal justice system rather than a principal or dean of students.

Kristen Devitt, director of the Office of School Safety at the Wisconsin Department of Justice, said schools need to think about why they want police in their schools and the goals their presence will accomplish. She said school resource officers, or SROs, should be a resource and support students in their educational journeys on issues such as truancy or dating violence.

“If the goal is to simply enforce the law and to arrest the kids, then a patrol officer could do that, if that was their main goal,” Devitt said. “Occasionally, there may be circumstances where behavior dictates law enforcement response. However, the overriding goal should be that they are building positive relationships with students and that they’re supporting the students, and they’re actually acting as a resource to the school community.”

Devitt said the decision to have police in schools needs to be made by the entire school community, including faculty, administrators — and especially students.

“A student should have a part in that, which I think creates a greater path to understanding and sets the tone that the students in this building are important and they’re important enough to be at the table and be a part of this conversation,” she said.

But Ion Meyn, an assistant professor at the UW Law School, sees no place for police in schools. Meyn, who studies racial disparities in the criminal justice system, said schools are often policed as “white spaces” where misbehavior by children of color is treated more harshly.

“They (police) should not be there,” Meyn said. “I don’t think that makes schools more safe. It doesn’t make students of color feel more safe. … I also think that if you have someone there, they’re just more apt to use them, and I think you should try much harder not to.”

Ajamou Butler has worked in schools in Milwaukee and La Crosse for 10 years as part of Heal the Hood MKE and a private consulting firm. Violence can be a problem, Butler said, but police are not necessarily the best equipped to handle it.

“There absolutely needs to be a team of responders who deal with violent outbursts amongst youth,” he said. “But that team of responders needs to be trained in conflict resolution as well as trauma-informed care work.”

Added Butler: “I think that there needs to be a significantly more impactful approach to dealing with youth who have adverse childhood experiences and mental health struggles. Police cannot help in those areas.”

Madison Cuts Police Ties

Increasing outcry and concerns that children of color are targeted have prompted some districts to remove police from schools. The trend quickened after a Minneapolis police officer murdered George Floyd, a Black man, in 2020. The Minneapolis, Oakland, Portland, Oregon and Seattle school systems ended their agreements with local law enforcement agencies. Two of the nation’s largest districts, Chicago and Los Angeles, slashed their budgets, the former by half and the latter by almost a third.

Savion Castro, Madison School District School board vice president, was among the members voting in 2020 to end that district’s contract with the Madison Police Department. Castro, who is Black and has a disability, saw the school resource officer program first-hand as a student at Madison’s LaFollette High School from 2009 to 2013.

“I didn’t receive any serious behavioral calls that would usually involve the SRO, but I certainly had friends that did,” Castro recalled. “It pretty much manifested from common misunderstandings amongst students and escalated to larger conflicts, and a staff member would usually call the SRO to help de-escalate that conflict, or they would call the SRO to escort a student out of the classroom. You just kind of had to witness that your peer was being removed out of the classroom for allegedly being disruptive or something like that.”

In Madison, a June 2019 video showed three officers from the Madison Police Department arresting a Black student who attended West High School. The then 17-year-old boy had mental health issues and had not taken his medication for several days, according to records of the incident. After the young man allegedly threatened to harm a school official, he left West and walked home. The teenager was arrested by officers there after reportedly threatening to harm another person doing construction work at the home, records show.

As the young man’s head was being held down, an officer put a bag, or “spit hood,” over his head and punched the side or back of his head at least three times. In a statement, then-Madison Police Chief Mike Koval said the young man had resisted arrest and spit on the officers, and “one officer delivered several strikes during the encounter in an attempt to gain control of the subject.” Madison365 did not identify the teen or his family to protect their privacy.

The incident was investigated by Madison police. As of Sept. 22, the department had reported no disciplinary actions related to it.

Castro said he wanted police out of Madison schools because of the negative impact their presence can have on Black and brown students and students with disabilities.

“I think what an officer ultimately does — it’s the threat of lethal violence, or of the criminal justice system,” Castro said. “I think it’s just another point of entry in our school systems, where students can be kind of whisked off into this school-to-prison pipeline.”

He added, “I think that there are more healthy, more effective means of helping students navigate conflict amongst each other.”

The Center for Public Integrity is a nonprofit investigative news organization in Washington, D.C. The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.