Wisconsin doctors are seeing a steady increase in the number of children diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes — a disease that primarily affects adults — which may be linked to COVID-19.

Data released last week by UW Health Kids shows a nearly 200 percent increase in the number of cases of Type 2 diabetes over the past four years.

While this is a trend medical experts have noticed for years, Dr. Elizabeth Mann, a pediatric endocrinologist and director of the Type 2 Diabetes Program at UW Health Kids, said it’s taken a worrisome turn recently.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“Since the beginning of the pandemic, we’ve just seen a sharp increase beyond what we had expected,” Mann said.

In 2018, 5.8 percent of pediatric patients with new onset diabetes at Madison’s American Family Children’s Hospital had Type 2. In 2021, that number grew to 16.4 percent. And so far in 2022, 1 in 6 pediatric patients at the children’s hospital with new onset diabetes has Type 2.

Mann said increased frequency is not the only concern.

“In kids, this Type 2 diabetes just acts a little bit more aggressively,” Mann said. “So it’s not only that we’re seeing Type 2 diabetes at younger ages, but it also seems to be a more severe form where kids are needing more medications and have more significant complications from it.”

Distinctions between Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes

In general, diabetes is a disease that affects how the body processes energy, but the two variations are completely different diseases.

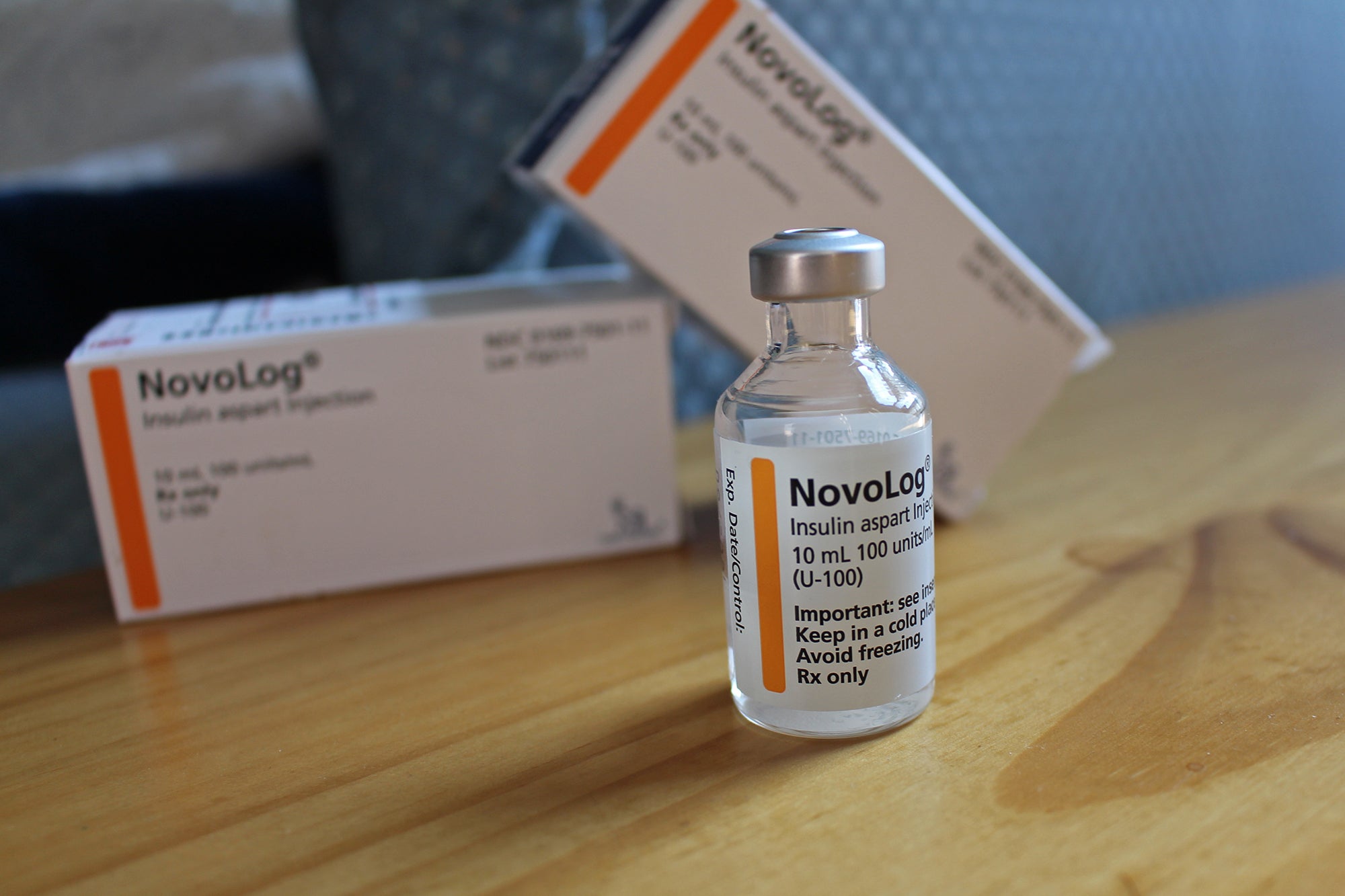

Type 1 diabetes, still the most common among children, is an autoimmune disorder in which the pancreas is not able to produce insulin properly. In Type 2 diabetes, the most prevalent form overall, the pancreas still produces insulin but the body has developed a resistance to it.

For a long time, Mann said, research suggested that only Type 1 could affect children — that’s why it was once called juvenile-onset diabetes. Type 2, which generally progresses slowly over decades, was considered adult-onset diabetes.

Mann said there is a common misconception that Type 2 diabetes is purely a result of diet and activity levels, which can lead to feelings of guilt or blame. She said genetics and epigenetics play a big role in making people more susceptible to the disease.

“It’s not that diet or exercise causes Type 2 diabetes to happen,” Mann said. “But for somebody who has a risk of developing Type 2 diabetes, changes in nutrition (and) decreased physical activity can all precipitate the onset. In other words, it can make it present all of a sudden, where it maybe wouldn’t have presented otherwise for years.”

Pandemic prompts changes in diet, exercise, mental health

This is why health experts are pointing to pandemic-related changes in diet, stress and physical activity as possible reasons for the increase in Type 2 diabetes among children.

And new research from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggests the COVID-19 virus itself may actually be precipitating new cases of diabetes in children.

For K-12 schools, this could mean an increased caseload for nurses, said Louise Wilson, a school nurse consultant for the Wisconsin Department of Instruction.

“If you have more and more students who have Type 2 diabetes, there’s more need for coordination of care management,” Wilson said. “That’ll involve more school nurse time, and obviously you have to balance that with all the other students with health needs.”

But Wilson is even more concerned about the long-term effects of COVID-19 on children.

“As we’re understanding more of what COVID does, and how it changes the body, I think (diabetes) won’t be the only condition that we see,” Wilson said.

Because COVID-19 causes inflammation of many internal organs, Wilson said we could see 30- and 40-year-olds with heart disease — something that usually shows up closer to age 60 or 70.

“If you have to live with a long-term health condition for 50 years, it’s different than living with it for 30 years,” Wilson said.

While diabetes never goes away, Mann said it can be managed, and those who are genetically predisposed to the disease may be able to stave off its onset with proper diet, exercise and regular medical check-ups.

If diabetes runs in your family, Mann recommends keeping an eye out for symptoms such as increased thirst, appetite and urination, and unintended weight loss.

But she said broader, societal changes are also part of the equation.

“It comes down to environment and stressors and access to things like healthy food and physical activity opportunities,” Mann said. “I think the trends are really important because it might help us recognize as a society there are things we need to do to support these vulnerable youth.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.