Friends and colleagues are mourning the death of Wisconsin State Archeologist James Skibo, a man they say emobodied the ethos of a “people’s archeologist.”

Skibo, 63, died Friday morning after a dive at Lake Mendota in Shorewood Hills.

The Dane County Medical Examiner’s Office is still investigating the cause and manner of his death, but a Madison fire department spokesperson said Skibo’s fellow divers told paramedics he had gone missing and had failed to surface for at least 10 minutes.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

He was found unresponsive by another diver in about 24 feet of water, and was transported to University of Wisconsin Hospital by first-responders who performed CPR, according to a news release from the Dane County Sheriff’s Office.

The dive was part of a routine work-up in preparation for this year’s maritime archeology season, according to a statement from the Wisconsin Historical Society.

“This is a tragic loss for many and our focus right now is on supporting the people closest to Jim, our employees, and all of those affected by his passing,” the statement said. “Jim was a certified diver and qualified for the depth of the dive as well as the equipment being used.”

Skibo, who went by “Jim,” was born in Crystal Falls, Michigan, in the state’s Upper Peninsula near its border with Wisconsin. He married his high school sweetheart, Becky Gamble, and both went to college at Northern Michigan University.

After getting his doctorate at the University of Arizona, Skibo spent 27 years teaching anthropology at Illinois State University. He came out of retirement to accept a job as Wisconsin’s state archeologist in 2021.

Skibo relished the public-facing role, said Gina Hunter, an associate professor of anthropology who became Skibo’s friend and colleague during his time at ISU.

“He wanted to uncover the old untold histories of people, and he wanted to create a sense of curiosity in the public about how we can discover things about the past, and to see the ways in which that makes our present more enriching,” Hunter said.

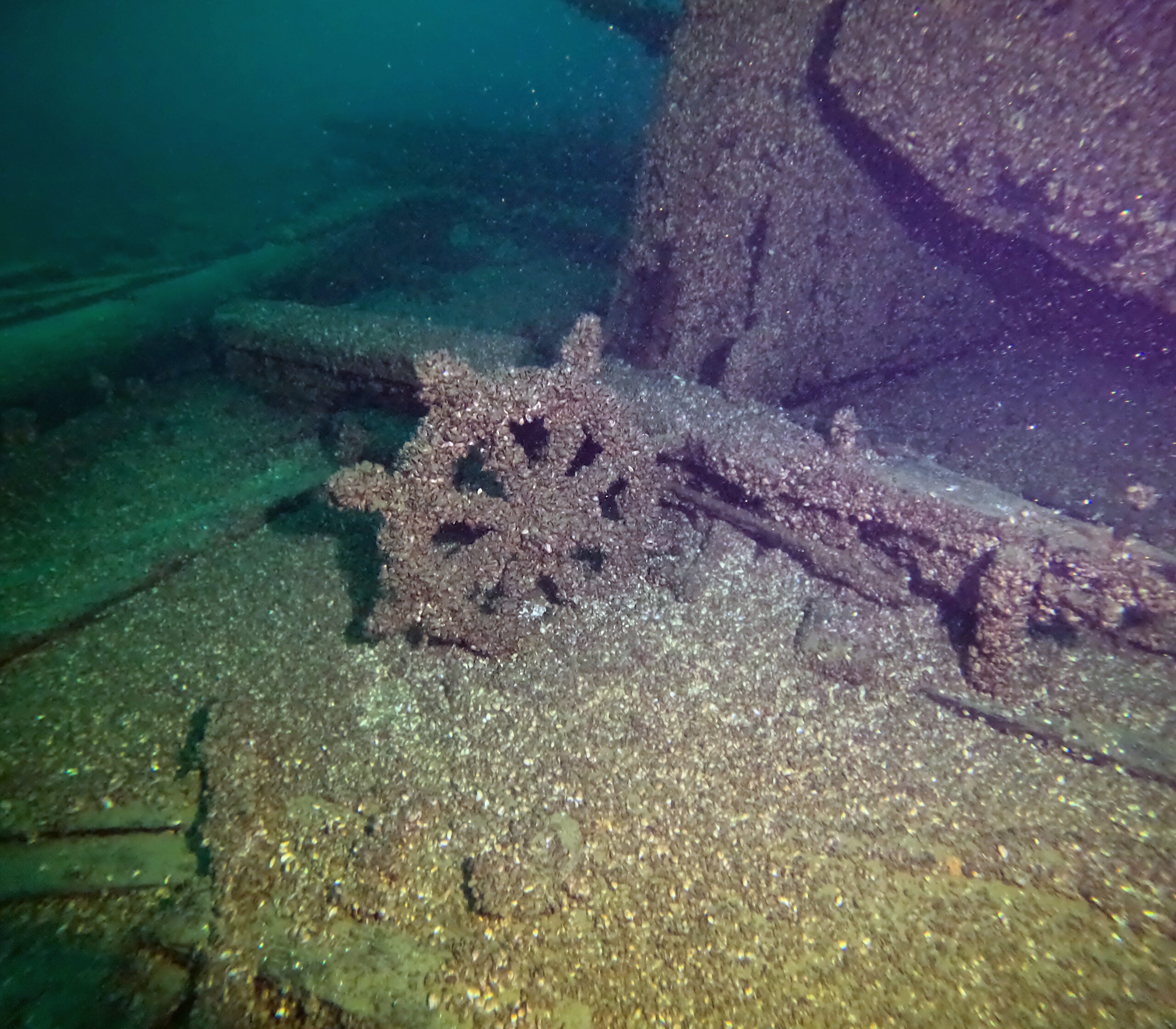

A highlight of Skibo’s career came last September, when he was part of a dive team that excavated a 3,000-year-old canoe from Lake Mendota in Madison. That dugout boat was the oldest of its kind ever discovered in the Great Lakes region. It came on the heels of the Wisconsin Historical Society uncovering a 1,200-year-old canoe in the same lake a year prior. Both canoes were first spotted by the Historical Society’s maritime archeologist Tamara Thomsen.

Bill Quackenbush, the historical preservation officer for the Ho-Chunk Nation, remembered Skibo as a personable archeologist who cared deeply about his work and about collaborating with Indigenous groups.

“He brought a lot to the table,” Quackenbush said. “And tribes, in kind, would open up just that much more there to assure that our collaborative efforts together kind of served a larger purpose.”

Among other projects, Skibo and Quakenbush worked together to establish a historic marker at the Wisconsin State Fairgrounds recognizing a Native American burial ground known as Tee Siskeja.

Skibo was adventurous and curious, his friends and colleagues said. His book “Ants for Breakfast” detailed his time living with the Kalinga people in a remote region of the Philippines. During his time at ISU, he led students on a field study on Lake Superior’s Grand Island, where they camped for weeks and had to haul water to use the bathroom.

“He was just full of gusto,” Hunter said. “He would get up early, he’d get right to work.”

That enthusiasm carried over to his teaching. Skibo had a keen sense of social justice and was passionate about making higher education accessible to everyone, said Joan Brehm, who chairs ISU’s sociology and anthropology department and considered Skibo a mentor.

“That is inspiring to somebody like myself when I was a junior colleague, and you’re feeling overwhelmed, and you’re not sure,” Brehm said. “‘Did I pick the right career? Is this really what I want to be doing? And can I make a difference?’ And you would look to someone like Jim and think, ‘You know, I can make a difference.’”

Skibo’s death has been a shock, said Seth Schneider, treasurer of the Wisconsin Archeological Society.

“He was a good archaeologist, and he was a good guy,” Schneider said. “The loss is very traumatic overall throughout the Wisconsin archeology community.”

Friends said Skibo was “goofy,” with a giggle that often punctuated his hearty laugh.

“Not all older grown men can be silly, but he could be silly,” Hunter said.

Hunter described Skibo as living his best life since his move to Madison. His two grown children, Matt and Sadie, live in the area. Skibo loved the city’s progressivism and its abundance of nature, Hunter said.

“He talked about not having enough time yet,” Hunter said. “Since they had moved there a couple years ago, he said he hadn’t had enough time yet to explore everything that Madison had to offer.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.