Blacklegged ticks or deer ticks are widely known to transmit Lyme disease, and now researchers have found that they may also be a pathway for spreading chronic wasting disease.

Those are the findings of a study led by the University of Wisconsin-Madison that were recently published in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Scientific Reports. The study examined whether ticks could carry an infectious dose of the deadly deer disease.

CWD is caused by a misfolded protein or prion. The disease attacks the brains of deer and other animals, causing drastic weight loss and death over time.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

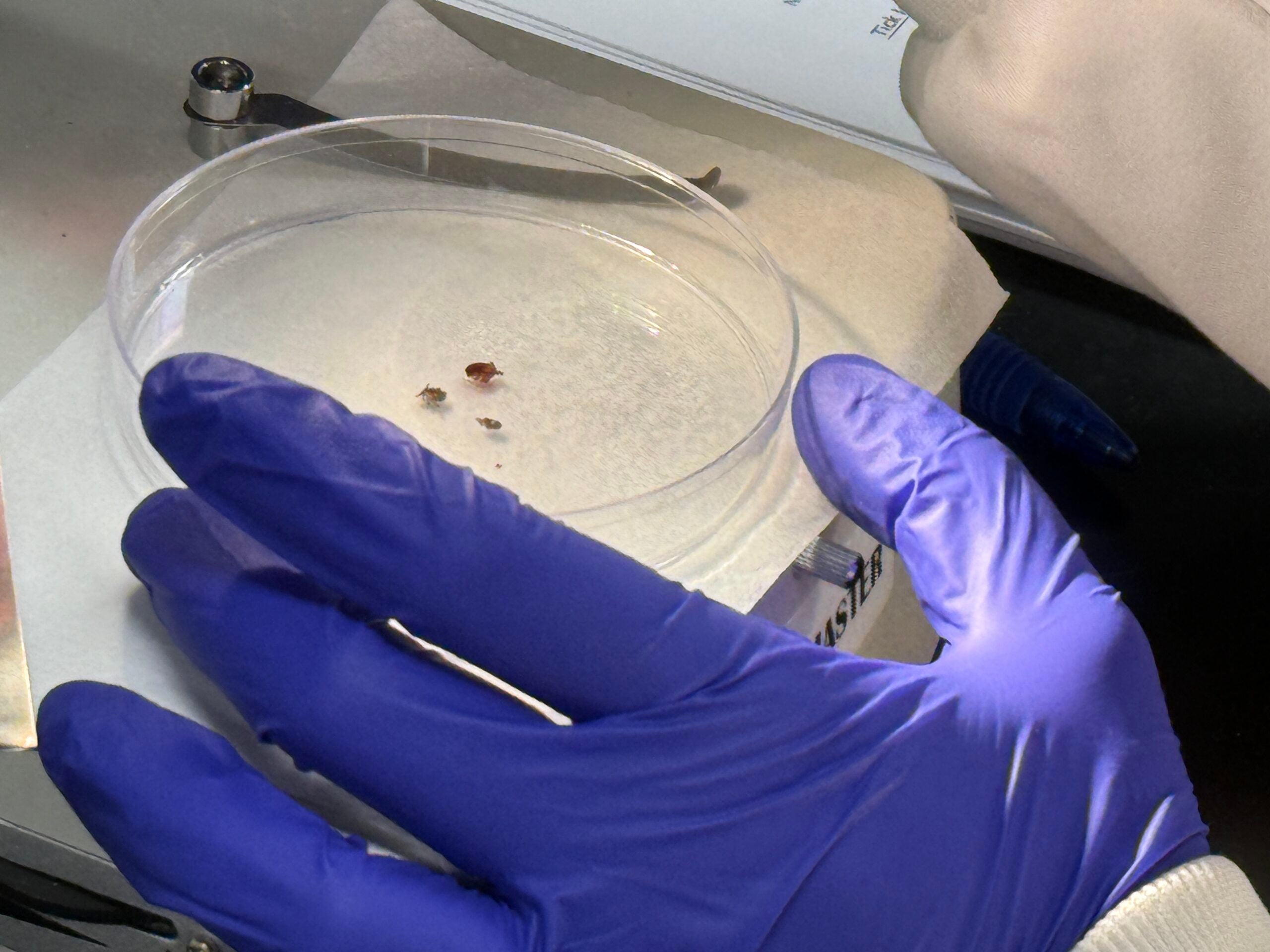

As part of the study, lead author Heather Inzalaco, a post-doctoral researcher at UW-Madison, gave blood with CWD-positive material to ticks in a lab. She found that the ticks both ingested and excreted CWD prions.

“They were taking it up, simultaneously eliminating some of it in their frass, which is just a fancy word for tick poo,” Inzalaco said. “So it was in both places.”

After proving ticks could ingest CWD prions, Inzalaco went through around 2,000 deer heads for ticks at the Department of Natural Resources’ CWD processing center to test results in the field. She then examined tick and ear samples from 174 tick-infested deer heads. Among them, there were 15 deer that tested positive for the disease, and samples showed a CWD prevalence ranging up to 40 percent in ticks that had fed on CWD-infected whitetail deer.

The findings showed ticks can take up enough CWD prions from infected blood that they could pose a risk of infecting deer, according to Stuart Lichtenberg. He’s a co-author of the study and a scientist at the Minnesota Center for Prion Research and Outreach at the University of Minnesota.

“It varied, but the ballpark range of what we were looking at was anywhere from slightly less than one to slightly over 10 infectious doses per tick,” Lichtenberg said. “That is to say that, if a deer ate one of these ticks, it’s possible that it could get sick from eating a single one of these infected ticks.”

Daniel Storm, fellow co-author and DNR research scientist, said the findings mean deer could possibly transmit the disease by grooming one another.

“We don’t know for sure that ingestion of one of these ticks would cause disease, but now we can say that it’s a possible route,” Storm said.

Researchers say the next step would be to prove the ticks are infectious by feeding them to lab mice that are vulnerable to CWD to see if they get sick.

“What we’ve found here is that it’s plausible,” Lichtenberg said. “What we haven’t actually proven is if it’s actually happening in the wild.“

While ticks are able to ingest CWD prions by feeding on infected deer, Inzalaco said there’s a low likelihood of humans being exposed to CWD through ticks.

“We don’t think that’s happening at this point,” she said. “There are no known cases of humans becoming infected from CWD.”

If ticks are playing a role in the prevalence of CWD, Inzalaco said the findings could be used to manage natural habitats and native plant communities to reduce the burden of ticks on deer.

Scientists believe the disease is likely spread through contact with blood, saliva, urine or feces of an infected deer, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It can also be spread by movement of the disease’s misfolded protein or infected deer from one location to another.

First detected near Mount Horeb in 2002, Wisconsin now has at least 60 counties the DNR considers CWD-affected. The disease has raised concerns among hunters, tribes, lawmakers and deer farm owners about the health of the state’s wild deer herd and captive deer. Hunting contributes about $2.5 billion to the state’s economy with the vast majority of that stemming from big game animals like deer.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.