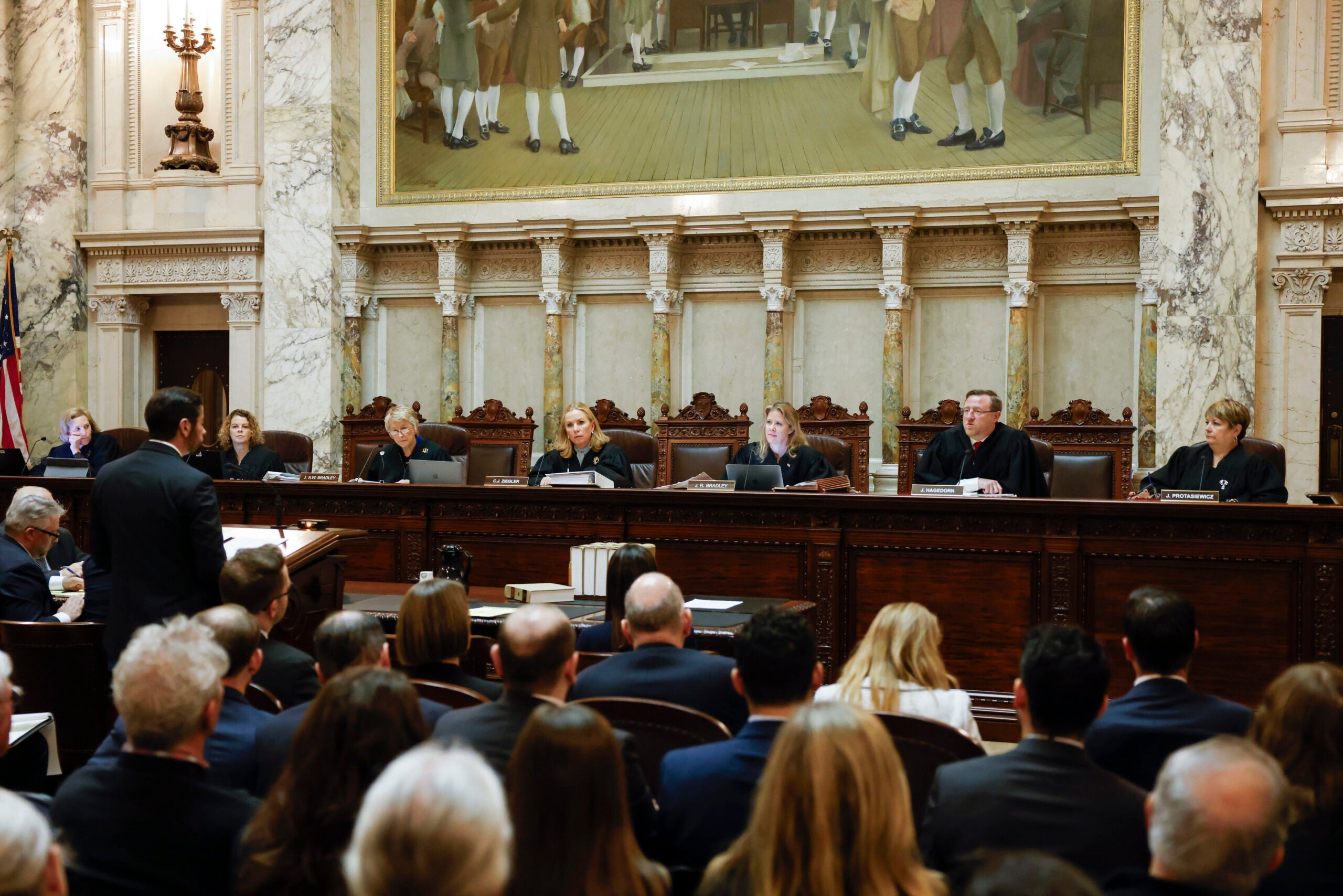

The Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled Thursday it would use the “least changes” redistricting plans submitted by Democratic Gov. Tony Evers as Wisconsin’s political maps for the next decade.

In the 4-3 decision, conservative swing Justice Brian Hagedorn wrote that of all the plans submitted, Evers’ plan best complied with criteria laid out by the court and met all the requirements of the Wisconsin and United States constitutions.

The court ruled in November that any new redistricting plan should make as few changes as possible to the maps the Republican-controlled Legislature passed and former Republican Gov. Scott Walker signed in 2011. That meant any new map approved by the court would lean Republican.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

According to an analysis by Marquette University research fellow John Johnson, Republicans would still keep strong majorities in the Legislature under Evers’ map. Even in a statewide tie election, Democrats would only be likely to win 38 out of 99 seats in the Assembly and 11 out of 33 seats in the Senate.

But choosing Evers’ maps over competing plans submitted by Republican members of Congress and the Legislature was, under the circumstances, a win for Democrats. In the Legislature, it could mean the difference between simple Republican majorities and supermajorities that could override any governor’s vetoes.

Evers celebrated the ruling in a statement.

“Hell yes,” said Evers. “The maps I submitted to the Court that were selected today are a vast improvement from the gerrymandered maps Wisconsin has had for the last decade and the even more gerrymandered Republican maps that I vetoed last year.”

Republicans didn’t say whether they planned to fight the ruling, although two of the court’s conservatives — Chief Justice Annette Ziegler and Justice Patience Roggensack — encouraged an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Hagedorn, who ruled with conservative justices in November, was joined by the court’s three liberal justices in his decision siding with Evers. He said the best way to measure “least change” is to choose the map that moves the fewest number of people into new districts.

“In this regard, the Governor’s proposed map is superior to every other proposal. It is the map with the least change,” Hagedorn wrote.

Among the proposed state legislative maps, Hagedorn said Evers’ map had “vastly superior core retention” for state Assembly districts.

“No maps from any other party perform nearly as well as the Governor’s on core retention,” Hagedorn said.

Republicans had urged the court to look at other metrics when deciding on new maps, stressing their proposals contained districts that were more equal in population. Hagedorn dismissed those arguments.

“Proposed maps are either lawful or they are not; no constitutional map is more constitutional than another,” Hagedorn wrote. “For our purposes, so long as a map complies with constitutional requirements, better performance on these metrics becomes commendable, but not constitutionally required.”

Writing for the dissent, Ziegler said Hagedorn’s ruling was “imbued with personal preference” and lacking in legal analysis.

“The majority’s decision to select Governor Tony Evers’ maps is an exercise of judicial activism, untethered to evidence, precedent, the Wisconsin Constitution, and basic principles of equal protection,” Ziegler wrote.

Ziegler also took issue with Hagedorn’s emphasis on “core retention” as a way to measure least changes, calling it “an invention, made after-the-fact to justify a policy preference.” While core retention hasn’t typically been considered among the bedrock principles of redistricting in Wisconsin, GOP lawmakers endorsed the idea in a resolution they passed in September.

Conservative justices urge appeal, citing racial issues

While the state Supreme Court’s say is typically final in the state court system, Ziegler and Roggensack took the unusual steps of suggesting appeals to the U.S. Supreme Court, suggesting Evers’ plan amounted to a racial gerrymander.

“What’s next?” Ziegler wrote. “Perhaps a federal court challenge before the United States Supreme Court.”

Roggensack’s suggestion was even more pointed.

“It is my hope that the United States Supreme Court will be asked to review Wisconsin’s unwarranted racial gerrymander,” she wrote.

Compliance with the federal Voting Rights Act, or VRA, is likely to be a key part of any future litigation. Evers’ map creates seven majority-Black districts, one more than the 2011 map. Hagedorn wrote that Evers’ map gives minority voters better representation.

“The risk of packing Black voters under a six-district configuration further suggests drawing seven majority-Black districts is appropriate to avoid minority vote dilution,” Hagedorn wrote.

However, Ziegler wrote the creation of a new majority-Black district was premature, arguing no clear violation of the Voting Rights Act was shown by Evers.

“Because the Governor has not demonstrated a VRA violation, there can be no race-based remedy,” she wrote.

While Republican legislative leaders didn’t say whether they planned to appeal the ruling, state Senate Majority Leader Devin LeMahieu, R-Oostburg, issued a statement alluding to the same issues highlighted by Ziegler.

“Tony Evers drew racially gerrymandered maps behind closed doors with no public input,” LeMahieu said. “His maps intentionally watered down minority representation for political gain.”

It would be unusual, though not unheard of, for the U.S. Supreme Court to hear an appeal of the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s redistricting ruling. Should the case end up there, it would be heard by a majority of justices chosen by Republican presidents.

The map could still be challenged on a more limited basis in an ongoing federal lawsuit brought by Democrats. That case had remained largely dormant while the state lawsuit proceeded.

The law firm representing one of the plaintiffs in that case, Black Leaders Organizing for Communities, issued a statement Thursday praising the state court’s ruling.

“Our clients presented strong evidence explaining the critical role of the Voting Rights Act,” read the statement from Law Forward attorney Mel Barnes. “These 7 districts do a better job protecting the votes of Black communities in Milwaukee from being unfairly diluted than the old maps.”

Conservative Justice Rebecca Bradley also wrote a dissent in which she suggested overturning a 1964 Wisconsin Supreme Court precedent on redistricting. That case banned the Legislature from passing redistricting as a joint resolution, which would let it sidestep the governor altogether.

“Unlike a fine wine, precedent does not necessarily get better with age,” Bradley wrote.

The 1964 ruling by the court was handed down unanimously. Since then, redistricting has typically been handled by federal courts or by the Legislature and governor, as was the case in 2011.

For more on the history of redistricting in Wisconsin and how it impacts political power in the state, check out WPR’s investigative podcast series, “Mapped Out.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.