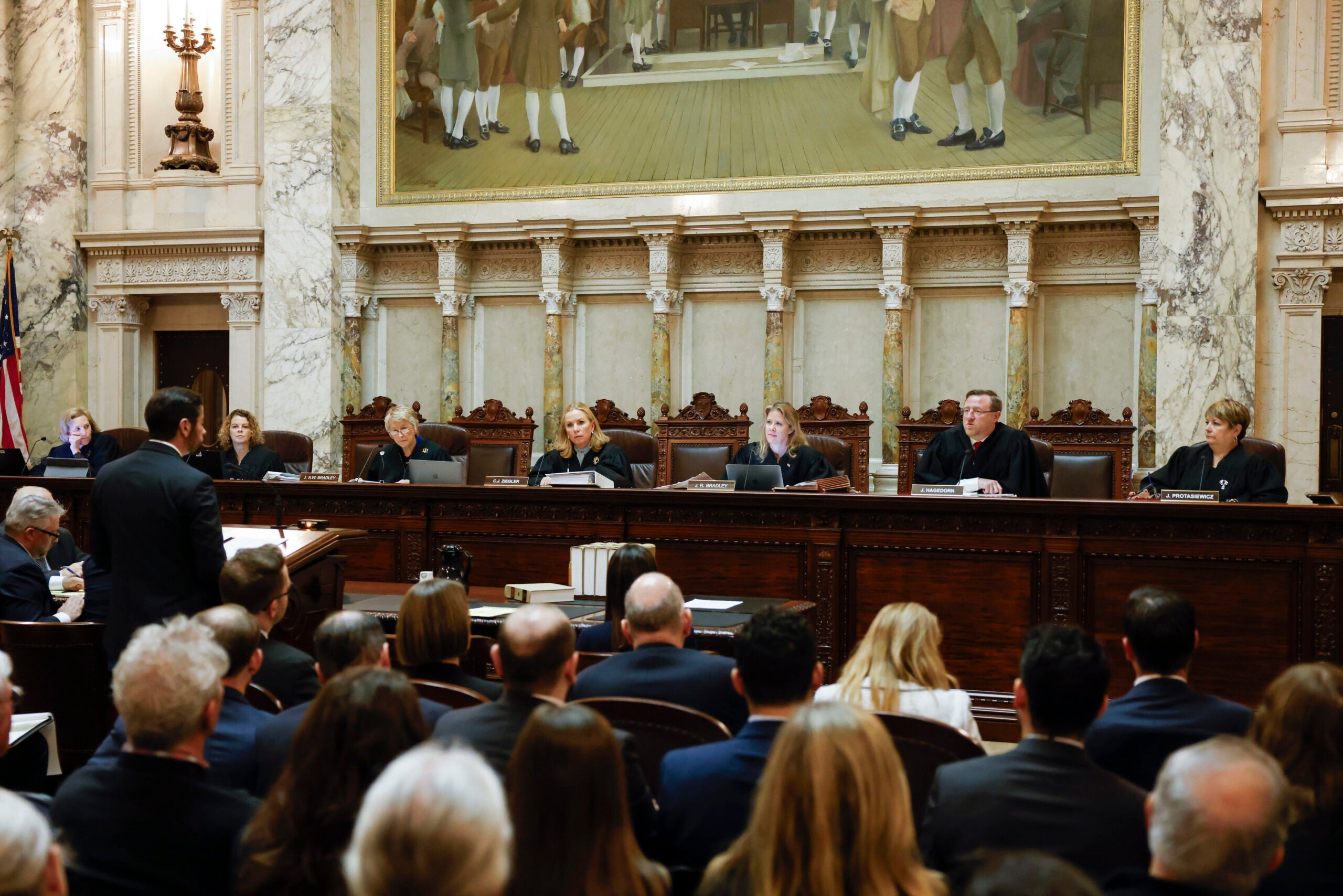

The Wisconsin Supreme Court heard arguments Monday in the last remaining state-based legal challenge to December’s lame-duck session of the state Legislature.

The case, brought by the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), argues the laws passed in the overnight session violate the state constitution’s separation of powers guarantee by infringing on the executive branch’s authority.

The lame-duck session included several measures approved by the GOP-controlled Legislature aimed at curtailing the powers of the governor and attorney general. The session was held shortly after Gov. Tony Evers and Attorney General Josh Kaul, both Democrats, were elected.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Those new limits include putting in place legislative approvals for things previously overseen exclusively by the governor, such as leaving federal lawsuits or seeking federal waivers for state laws.

The lame-duck laws also require the attorney general to seek approval before settling any lawsuits involving the state. That has led to a months-long standoff between Kaul and GOP lawmakers, affecting more than 15 cases, some of which could bring millions of dollars into state coffers.

Justices on the state’s highest court dedicated two hours to arguments — twice the amount of time normally allotted for such proceedings.

Arguments Over Role Of Attorney General

A large portion of the arguments were dedicated to a discussion of the Legislature’s new power to approve legal settlements involving the state.

During those arguments, both conservative and liberal justices seemed to question the law.

“You can grind to a complete halt any kind of litigation the attorney general is conducting,” said Justice Rebecca Dallet, one of the court’s liberals, to the lawyer representing GOP lawmakers. “So the buck would stop with the Legislature. That’s not a seat at the table … that’s you are the one making that decision.”

Justice Daniel Kelly, part of the court’s 5-2 conservative majority, pointed out the state constitution gives the Legislature power to dictate the attorney general’s duties, but questioned who could assume those powers if they’re taken away.

“The Legislature can deprive the attorney general of the entirety of his authority and consign him to twiddling his thumbs all day long,” Kelly said. “However, that doesn’t answer the question of where that power goes after it’s withdrawn from the attorney general.”

Justice Annette Ziegler, another of the court’s conservatives, and Justice Ann Walsh Bradley, a liberal-backed justice, both questioned whether the Legislature has the authority to represent the state in legal action, as the attorney general does.

Bradley repeatedly asked the lawyer representing GOP lawmakers, Misha Tseytlin, to point to the part of the state constitution that specifies the Legislature can represent the state in such action.

Tseytlin argued limits on the attorney general don’t violate separation of powers guarantees between the executive and legislative branches of government because the attorney general is not part of the executive branch.

Instead, Tseytlin argued the office falls under a different part of the constitution outlining administrative offices, thereby making it part of a fourth branch of government, called the “administrative branch.”

“The attorney general’s power is not grounded in the constitution,” Tseytlin said. “Whatever the attorney general’s power is, it’s not the executive power.”

Questions Regarding Executive Power

A lame-duck law that allows lawmakers to suspend administrative rules written by the Evers administration was also a major focus for justices.

Justice Rebecca Bradley, one of the court’s conservatives, argued that provision should be allowed to stand, as the Legislature gave agencies power to write rules in the first place.

She said asking lawmakers to use the legislative process to suspend a rule would be unreasonable.

“How can the Legislature be required to go through a lawmaking process to suspend a rule that was made through delegated legislative power?” Bradley asked.

Justices also asked questions about a law that put in place additional requirements for “guidance documents” issued by the Evers administration, including things like informational booklets.

Lester Pines, a lawyer for the governor, argued the case should be sent back to a lower court so more “fact finding” could take place related to the possibly burdensome effect of those new requirements.

Justices didn’t ask questions about a high-profile law passed during the lame-duck session that requires lawmakers to approve the state leaving federal lawsuits. That has been a major point of contention between lawmakers and the governor, as Evers campaigned on withdrawing the state from a multi-state federal lawsuit challenging the Affordable Care Act.

Evers was able to follow through on that campaign promise during a short period of time in which the lame-duck laws were put on hold by courts.

Next Steps For Lame-Duck Challenges

The Supreme Court could issue its ruling on the case at any point. They could choose to send the challenge back to a lower court or to dismiss it entirely.

The SEIU lawsuit is one of four legal challenges to the lame-duck session. Two lawsuits are finished, with judges ruling in favor of GOP lawmakers. The fourth challenge is awaiting a decision by the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals in Chicago.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.