Wisconsin’s tax burden hit its lowest level in two decades in 2020, according to an annual report released Tuesday by the Wisconsin Policy Forum.

The report looked at new federal data, showing Wisconsin’s state and local tax collections rose just 1.7 percent in 2020 — the smallest increase since 2015.

Jason Stein, Wisconsin Policy Forum research director and author of the report, said the economy was relatively stable in the early months of the pandemic compared to other states.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“The takeaway here is that we did seem to, in the early days of the pandemic in Wisconsin, weather that a little bit better than other states,” he said.

Despite the low tax burden, Wisconsin’s national tax ranking rose from 24th-highest in the country in 2019 to 18th in 2020.

“It’s a little bit paradoxical,” Stein said, adding he doesn’t think the rise in rankings “reflects any kind of policy decisions that the state really made.”

Ross Milton is an assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison La Follette School of Public Affairs. He said the study offers a clear picture of the state’s tax levels.

“There’s a sense among many people that Wisconsin is a high-tax state, and that we should change that,” he said. “This report reflects the fact that Wisconsin is really a moderate tax state.”

Milton said states that relied heavily on hospitality and tourism taxes during the pandemic may have fared worse due to closures and stay-at-home orders. But Wisconsin relies heavily on property taxes, which remained relatively stable at that time.

“Nobody was traveling in the last few months of that fiscal year, and that hurt states like Florida that generate a large amount of tax revenue from that type of commerce,” Milton said. “If you think about how Wisconsin’s rankings change relative to other states … (it) really says more about those states than it does about Wisconsin necessarily.”

The Wisconsin Policy Forum looked at the taxes collected from residents at the state and local levels across Wisconsin as a share of people’s personal income.

Over the past 20 years, the Wisconsin tax burden has dropped from 12.5 percent of personal income in 2000 to 10.1 percent in 2020.

In 2000, Wisconsin’s tax burden was slightly higher than its neighboring states. But it’s now the second-lowest, compared to Michigan, Iowa, Minnesota and Illinois, reflecting a shift with the national average and in the region.

At the same time, the state’s ranking for K-12 spending dropped from being in the top 10 nationally to below the national average.

Stein wrote in the report that “the decrease in the state’s tax burden over the past 20 years has translated into a decrease in state and local spending overall and on education in particular.”

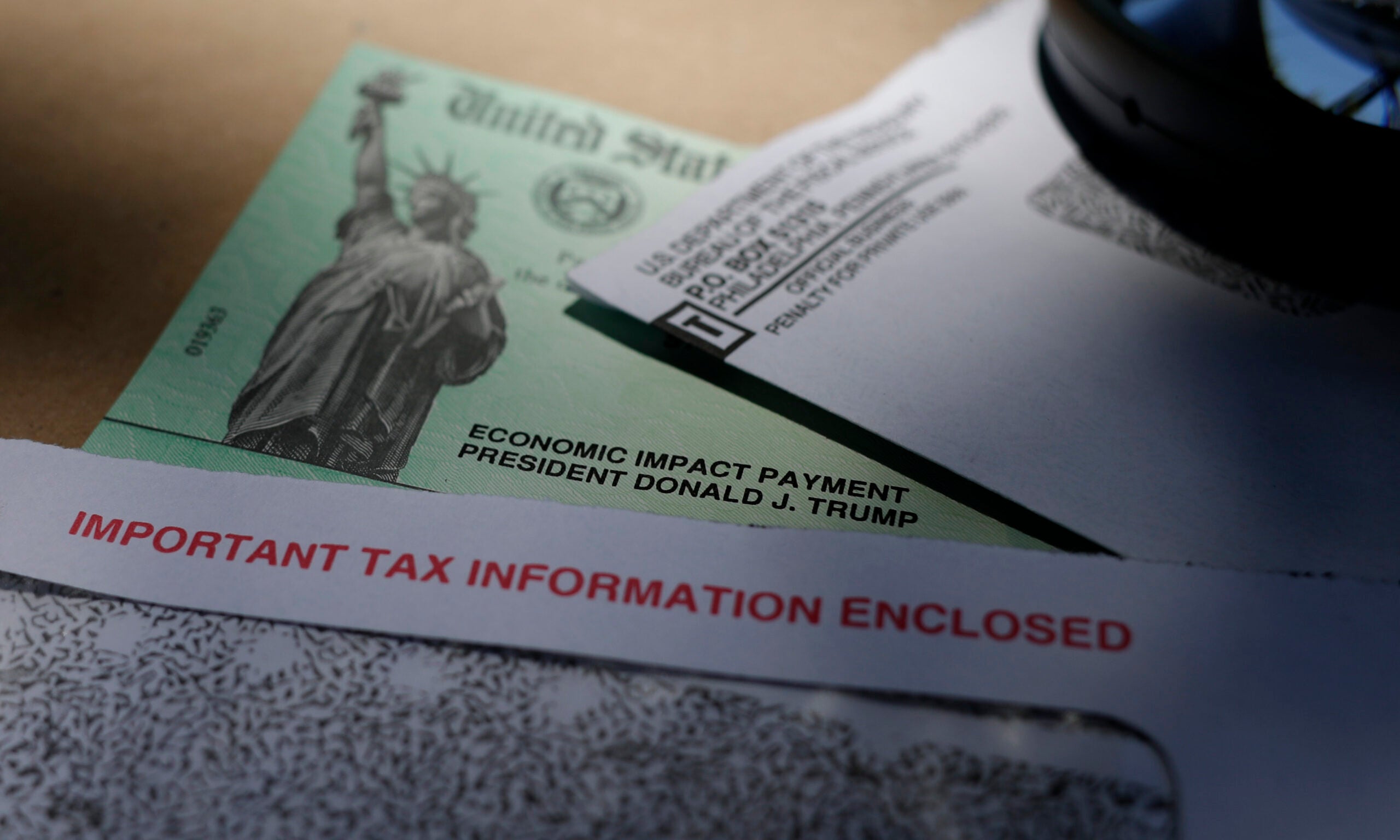

He said a variety of factors have contributed to the state’s rankings. Wisconsin doesn’t get as much federal aid as some other states, but between 2019 and 2020, federal revenue to the state grew from $10.9 billion to $13.65 billion through pandemic aid.

Next year’s tax burden is likely to be affected by a $1 billion income tax cut enacted in the 2021-2023 state budget. State economies are also expected to continue to recover as the pandemic wanes.

The next state budget could include another tax cut, as Wisconsin ended its fiscal year with a record $4.3 billion budget surplus. Stein said that while Democratic Gov. Tony Evers and Republican challenger Tim Michels would approach the surplus differently, they’ve both talked about using part of the money for tax cuts.

The decisions made by state leaders have “far-reaching implications for what people pay in taxes, what services people receive, like education, and ultimately, the trajectory of our state,” Stein said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.