Evelyn Cortes traces her first memory of wanting to be a teacher back to when she was 10 or 11 years old, playing with her younger sister.

“I would play the teacher and she was my student, and I would imagine the classroom,” she said.

Her initial dream became more concrete during her high school years in Beloit, when she was able to take classes on early childhood education and get a feel for teaching younger kids. One of her teachers was also a college instructor for early childhood education.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“She told me everything about the program, and I got very excited,” Cortes said. “I went in and talked to my counselor at the high school, and I told her my plans.”

Her counselor and teachers helped guide Cortes through getting her associate’s degree from Blackhawk Technical College to save money, and then moving on to the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, where she’s currently a junior, for her bachelor’s degree. They also directed her toward scholarships, in particular the Grow Your Own Multicultural Teacher Scholarship.

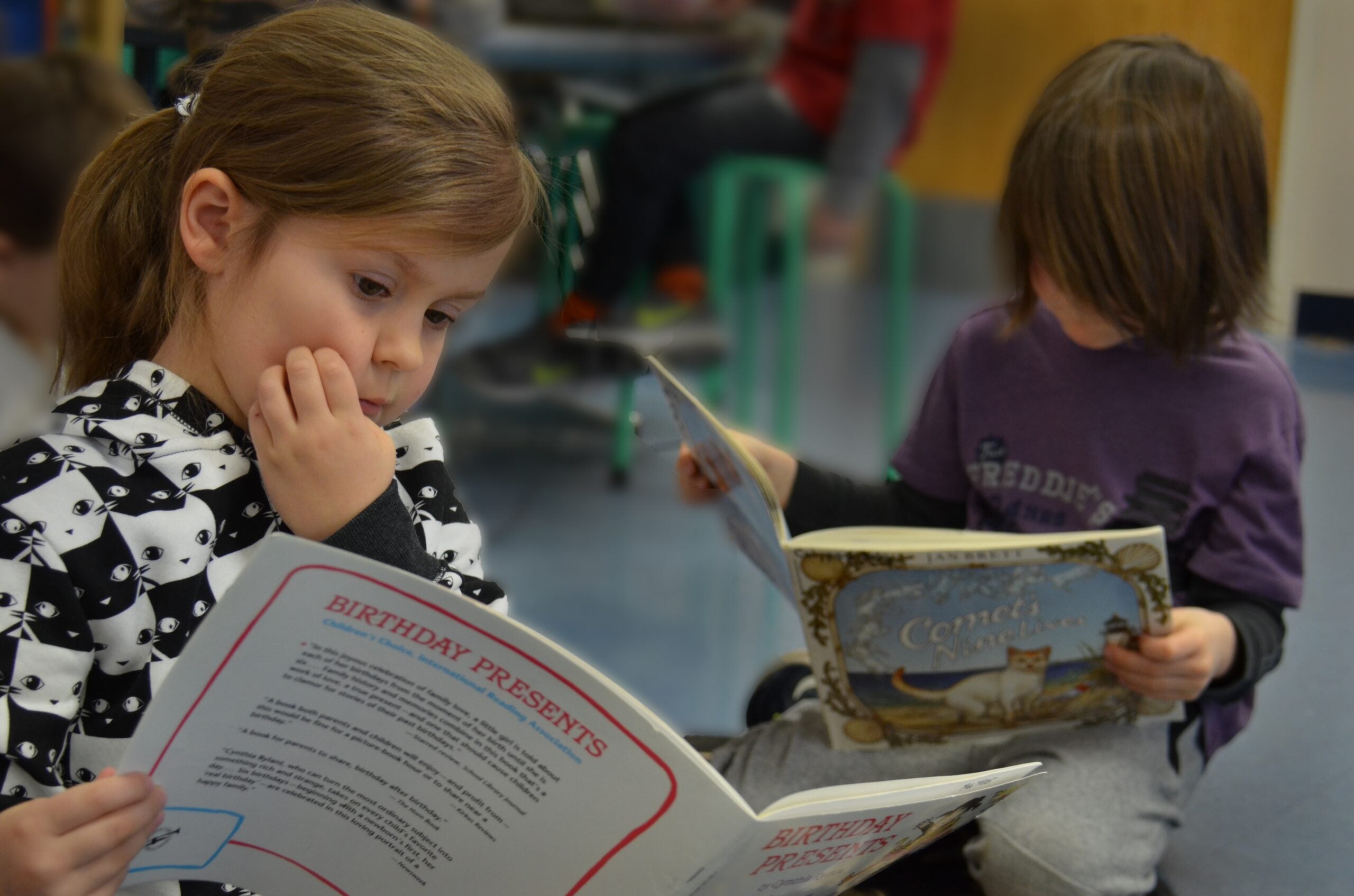

A recent report from the Wisconsin Policy Forum shows that despite evidence that a more racially diverse teaching staff leads to better and more equitable outcomes for students, Wisconsin’s teachers are overwhelmingly white.

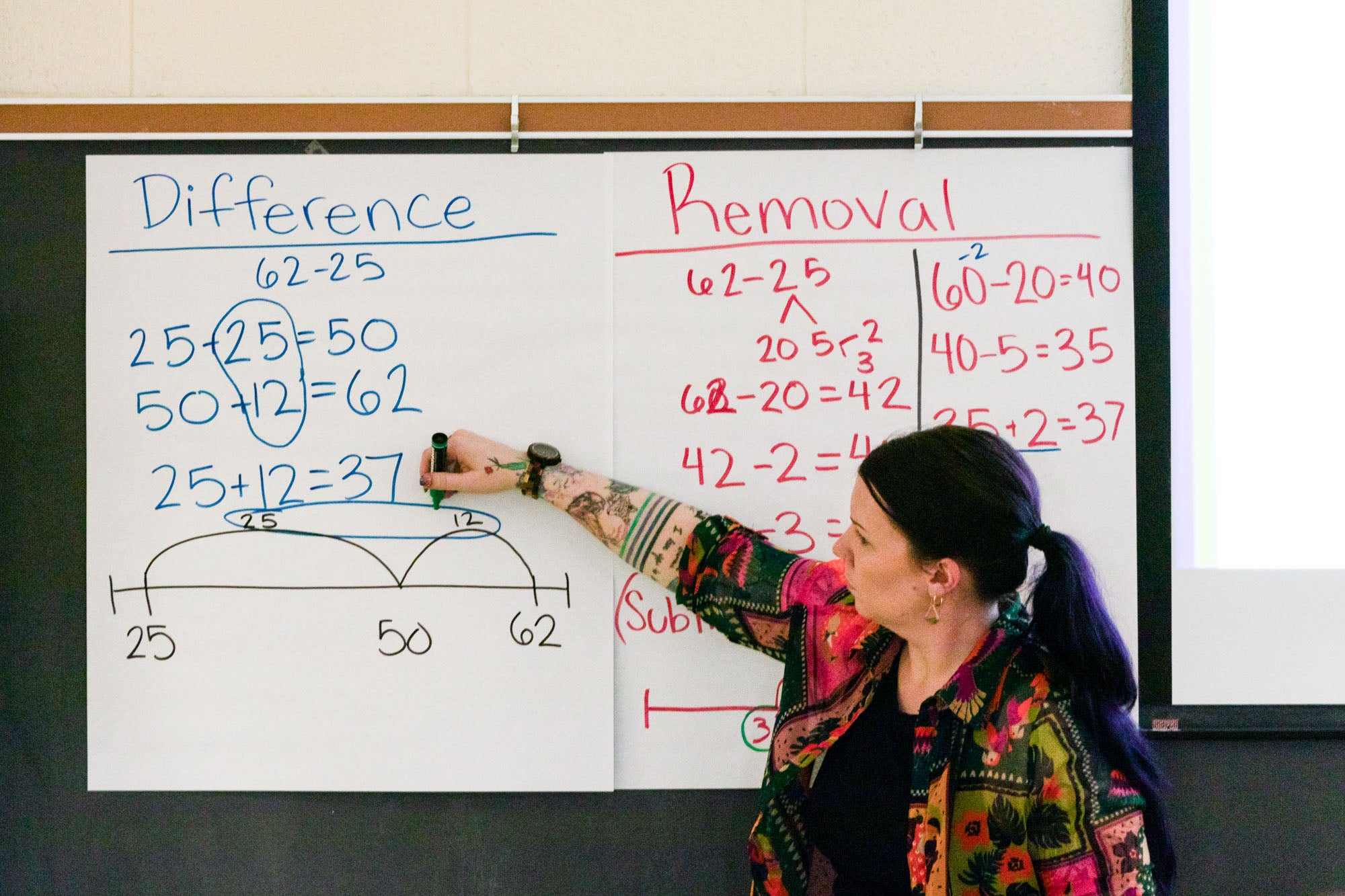

Many school districts, nonprofits and universities in Wisconsin and around the country have turned to “grow your own” programs to attract students into teaching, and offer them money and support through the education process in exchange for a commitment to work in their local districts. Beloit’s program was modeled after one in Janesville. The Madison Metropolitan School District also has a program, as do Racine and Mauston. Some target college-bound high school students, like Cortes, while others aim to provide a pathway for people already working in education fields, like paraprofessionals, toward their teacher certifications.

Cortes is the first in her family to go to college. She said figuring out how to pay for school was her top concern. With the $5,000 per year she gets as one of the district’s two current Grow Your Own recipients, she can cover her tuition, books and fees, which, along with living at home, put college within reach.

Michelle Hendrix-Nora, principal of Beloit’s McNeel Intermediate School, said she’d like to see the district’s “Grow Your Own” scholarship expand to support more students coming out of district high schools, as well as educational staff like paraprofessionals, which she said are the largest diverse population of school employees.

Paraprofessionals include positions like special education assistants, teachers aids and tutors.

“They’re the ones in our classrooms every day in our schools, working just as hard as everybody else,” she said. “To encourage them and support them to go back to school, financially and academically, to get their degrees, to come back to be our teachers, because those are the ones who live here in Beloit, those are the ones who are going to stay — my hope is that we can expand to help them as well.”

Hendrix-Nora said seeing teachers of different races and cultural backgrounds is important for all students.

“It’s not even important just for our minority students, to see someone teach them, it’s important to everyone to see that person in a light, that, for example, there can be a Black man English teacher,” she said. “A lot of times, even today, they don’t have that interaction with a lot of people outside their own race and culture — so if school’s not the place to provide those positive role models to everybody, where do we start?”

While the Wisconsin Policy Forum’s previous report on teacher diversity looked at the numbers and tried to identify some reasons the teacher pipeline leaks people of color at each step, the newer report, released Tuesday, looked at what solutions are being tried locally — and what more can be done — in addition to barriers that keep teachers of color out.

At the state level, the report identifies five major areas, particularly focused around accountability, support, centralized data collection and investment. [[{“fid”:”1465231″,”view_mode”:”full_width”,”fields”:{“class”:”media-element file-full-width media-wysiwyg-align-right”,”data-delta”:”1″,”format”:”full_width”,”alignment”:”right”,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3EThe%20five%20areas%20of%20state-level%20policy%20identified%20in%20the%20Wisconsin%20Policy%20Forum’s%20report%20on%20potential%20solutions%20to%20the%20lack%20of%20teacher%20diversity.%20Photo%20co%3Cem%3Eurtesy%20Wisconsin%20Policy%20Forum.%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:false,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:false},”type”:”media”,”field_deltas”:{“1”:{“class”:”media-element file-full-width media-wysiwyg-align-right”,”data-delta”:”1″,”format”:”full_width”,”alignment”:”right”,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3EThe%20five%20areas%20of%20state-level%20policy%20identified%20in%20the%20Wisconsin%20Policy%20Forum’s%20report%20on%20potential%20solutions%20to%20the%20lack%20of%20teacher%20diversity.%20Photo%20co%3Cem%3Eurtesy%20Wisconsin%20Policy%20Forum.%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:false,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:false}},”link_text”:false,”attributes”:{“class”:”media-element file-full-width media-wysiwyg-align-right”,”data-delta”:”1″}}]]

There are local programs, like Beloit’s Grow Your Own scholarship, but Chapman said the state can help back them up, share information across programs and rework some of the policies that can be barriers to people who would be good teachers being able to get the right certifications.

“The state can be resourcing those (diversity) efforts better, but also adding to them,” she said. “To say, we are going to put our money, and our statutes and requirements, where our mouth is, and we’re going to prioritize this.”

On a more localized level, Chapman noted that with the low numbers of nonwhite teachers, those studying to become educators or who are teaching in classrooms often find themselves being the only teacher of their particular race or cultural background, or one of very few, which can be even more isolating. Teachers are likeliest to leave the profession in their first few years, and the added layer of isolation, or having to take on extra work around diversity and inclusion efforts, can exacerbate the stresses that push teachers out.

In Beloit, Hendrix-Nora said part of the reason expanding the Grow Your Own scholarship would be so beneficial is to create a bigger cohort of teachers-in-training who can support each other through their education and adjustment into a classroom.

“If they don’t feel like they have the support within their buildings, with other colleagues or staff or administrators — how do we create that environment, and support them through their first years of education?” she said.

Chapman conducted focus groups with Wisconsin teachers, administrators, education officials and others involved in the teacher pipeline to try to understand what was driving away teachers and potential teachers. She found that the concerns varied — some Native American teachers she talked to, for instance, noted that they grew up with a culture built around respecting elders, which made it difficult to adapt to a higher education system where they were sometimes expected to challenge their professors. Black male teachers, in particular, said they often felt “pigeonholed into positions where they are called in to act as the ‘enforcer’” for students with behavioral challenges, according to the report.

From teacher after teacher, she heard about the underlying barrier of racial bias throughout the educational system, both in the pathways to becoming a teacher and in the schools where teachers start their careers.

“Despite efforts and philosophies to the contrary, there are systematic obstacles that appear to affect teachers of color and students of color more than white people,” she said. “If we don’t look at the underlying biases that cause these structural issues, we’ll be treading water — we can make incremental change, but we’ve got to sort of look at what’s holding these structural problems in place.”

Without looking at those deeper structural issues embedded in every level of the education system, she said, it will be much harder to bring teacher demographics more in line with those of their students, even with robust “grow your own” programs, scholarships, teacher residencies and other solutions.

Cortes, the Whitewater junior, helps translate in Spanish between parents and teachers during teacher conferences and Individualized Education Plan (IEP) meetings, which she said has helped her see a range of effective communication and teaching strategies. She said she’s excited to be able to bring those perspectives back to the same classrooms she tried to duplicate for her sister growing up.

“My dream when I was going into early childhood (education) was to come back to Beloit, and teach in one of the schools where I was taught, and teach with some of the teachers I was taught by,” she said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.