In late January, Ann Marra learned that her 91-year-old mother was being evicted from her assisted living home.

That’s when Emerald Bay Retirement Community & Memory Care in Brown County’s Village of Hobart sent notices to residents telling them that the facility would no longer accept Medicaid funding due to insufficient reimbursement, rising labor costs and inflation.

Across Wisconsin, senior care facilities are facing challenges with staffing and budgeting. It’s led to an increase in the number of nursing home complaints received by the state, and in extreme cases has meant families like Marra’s have had to find new accommodations for aging parents.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

After paying out-of-pocket for her first two years at Emerald Bay, Marra’s mother, Shirley Holtz, had been on Medicaid for about three years when Marra received the eviction notice.

In a February press conference, Emerald Bay officials said they tried to negotiate for better reimbursement to no avail. They said continuing to care for Medicaid recipients would raise costs for private-pay residents.

“We can’t keep passing on the economic crazy to our folks that are in their 80s and 90s,” said Katherine Tegen, CEO of BAKA Enterprises, Emerald Bay’s parent company. “It’s not just one community. It’s a huge issue that we’ve got to address, not just in our county (or) our state.”

At the time, the situation felt “unreal,” Marra said.

“It was in the middle of winter, Mom was in hospice and she’s 91 years old with dementia — and they’re evicting her,” Marra said. “It was just disgusting to us. The family members were just really appalled by this.”

Marra isn’t the only Wisconsinite who’s had to move a loved one from a long-term care facility in recent years. Between fall 2022 and April 2023, there were at least 50 Medicaid-related evictions in Wisconsin, according to The Washington Post.

In fact, nearly two dozen nursing homes have closed across the state since 2020, and 42 closed between 2016 and April 2021, according to LeadingAge Wisconsin, a senior living advocacy group.

Holtz’s family scrambled to look for another facility that would accept her. She moved out of Emerald Bay in mid-March. Within a week at her new facility, Marra said her mother had gotten weak and had stopped walking.

“I went on a vacation. Two weeks later, I came home, and I didn’t even hardly recognize her,” Marra said. “She had lost like 15 (to) 20 pounds in the 10 days that I was gone. She had stopped eating, stopped drinking, and she wasn’t responsive when I got there. And then she passed away.”

Holtz died on April 3 at Alpha Senior Concepts in Howard with her family at her side. Marra said she believes the move played a role in her mother’s health deteriorating.

Long-term care facilities face tough situation on multiple fronts

While not all facilities take steps to evict all Medicaid recipients, they all face similar struggles in maintaining staff and balancing their books.

Providers also face what they call a “caregiver crisis,” as caregiver vacancies rose from 23.8 percent in 2020 to 27.8 percent last year. In fact, as of last March, 51 percent of nursing facilities in Wisconsin reported staffing shortages, according to the nonprofit health policy organization KFF.

This month, the Biden administration proposed comprehensive staffing requirements for nursing homes. If adopted, the new rule would require about three-fourths of all long-term care facilities to hire additional staff, NPR reported. But as facilities already face staffing shortages, it’s not clear where those workers would come from.

Medicaid reimbursement challenges and workforce shortages have both contributed to facility closures in recent years, said John Sauer, retired president of LeadingAge Wisconsin who spent over three decades advocating for long-term care facilities.

“If we cannot offer competitive wages and benefits because of the Medicaid program, then we basically have a reality that doesn’t make continued operating of these nursing facilities financially viable,” Sauer said.

Staffing shortages have forced many facilities to operate with elevated vacancy rates because they don’t have enough employees to care for residents in a full facility, regardless of demand, Sauer said.

That’s as the state’s population is aging, with many Baby Boomers reaching or nearing retirement age. A recent report by Wisconsin Manufacturers and Commerce, the state’s largest business lobbyist, found that Wisconsin is one of only 14 states with a median age over 40.

“We really need nursing homes, given the population and demographic shifts in our state and throughout the country,” Sauer said.

Jim Orheim, the current president of LeadingAge Wisconsin, said staffing challenges facing long-term care facilities aren’t new but have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We saw a lot of really seasoned staff retire, and we saw an insufficient pipeline of new talent moving into these roles,” he said. “At the same time, we continue to see the aging population growing, that’s going to continue to put stress on the system.”

‘Caregiver crisis’ leads to more complaints against long-term care facilities

There’s evidence that the caregiver shortage has led to worse care for patients and residents.

Last year, the state Department of Health Services received more complaints about nursing homes and assisted living facilities than in any of the four prior years, according to data from the department. In 2022, DHS received 2,361 complaints about nursing homes and 2,284 at assisted living facilities, up from 1,984 and 1,923, respectively, the previous year. Assisted living facilities included adult family homes, community-based residential facilities and residential care apartment complexes. The department could not provide data on complaints submitted so far in 2023.

The surge in complaints against nursing homes during the pandemic also contributed to a backlog of inspections. Last year, the state struggled to hire enough qualified workers to conduct inspections within federally mandated time limits, according to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. In response, the state did hire two private companies to inspect nursing homes.

In a statement, DHS spokesperson Elizabeth Goodsitt said increased complaints to the state last year may have been the result of staffing shortages at health and residential care facilities making it more difficult for families to make complaints directly with an institution.

“This often results in families reaching out to the state survey agency to formally file a complaint, which has resulted in a greater-than-normal complaint workload for Wisconsin nursing home surveyors, as noted in the significant surge in the number of complaints,” she said.

Matthew Boller, a Madison-based attorney who specializes in elder abuse and neglect cases, said his firm saw an increase of roughly 25 percent in calls alleging abuse and neglect in the second half of 2020. In the last year and a half, the firm has seen another 30 percent increase, he said.

“That is the result of obviously poor care, but also it certainly does relate to understaffing in skilled nursing facilities and assisted living facilities in Wisconsin,” he said.

Boller said the cases his firm takes on are “always preventable,” generally involving victims who are unable to care for themselves and need 24-hour supervision.

“There are literally a litany of neglectful cases that occur in nursing homes on a daily basis that include residents not getting enough food or water to drink resulting in catastrophic results,” he said. “(Or) not following physician’s orders or following up on what are simple, very basic needs of the resident that — if not treated — can result in catastrophic injuries, infections and deaths.”

In fact, two of the nation’s worst-rated nursing homes are in the Wisconsin cities of Black River Falls and West Allis, according to a report by the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. In Black River Falls, the newspaper reported that a 79-year-old woman, with a history of trying to escape, disappeared last August. She was later found in the middle of a nearby road. At the West Allis facility, medication errors by nurses led to a resident becoming “gravely ill” in 2021, the Journal Sentinel reported. The facility also had trouble answering calls from residents in distress and had paint peeling off walls.

Challenges prompt rural county to consider selling its nursing home

The challenges facing long-term care facilities have been especially felt in Lincoln County, where the County Board is contemplating selling the nursing home it’s owned since the 1950s.

Pine Crest Nursing Home in Merrill has struggled to operate in the black in recent years. A March report from the county estimated the facility had a $1.2 million deficit last year, and requires an additional $11 million in maintenance. Since 2014, the facility has lost roughly $9 million, according to a May 12 document.

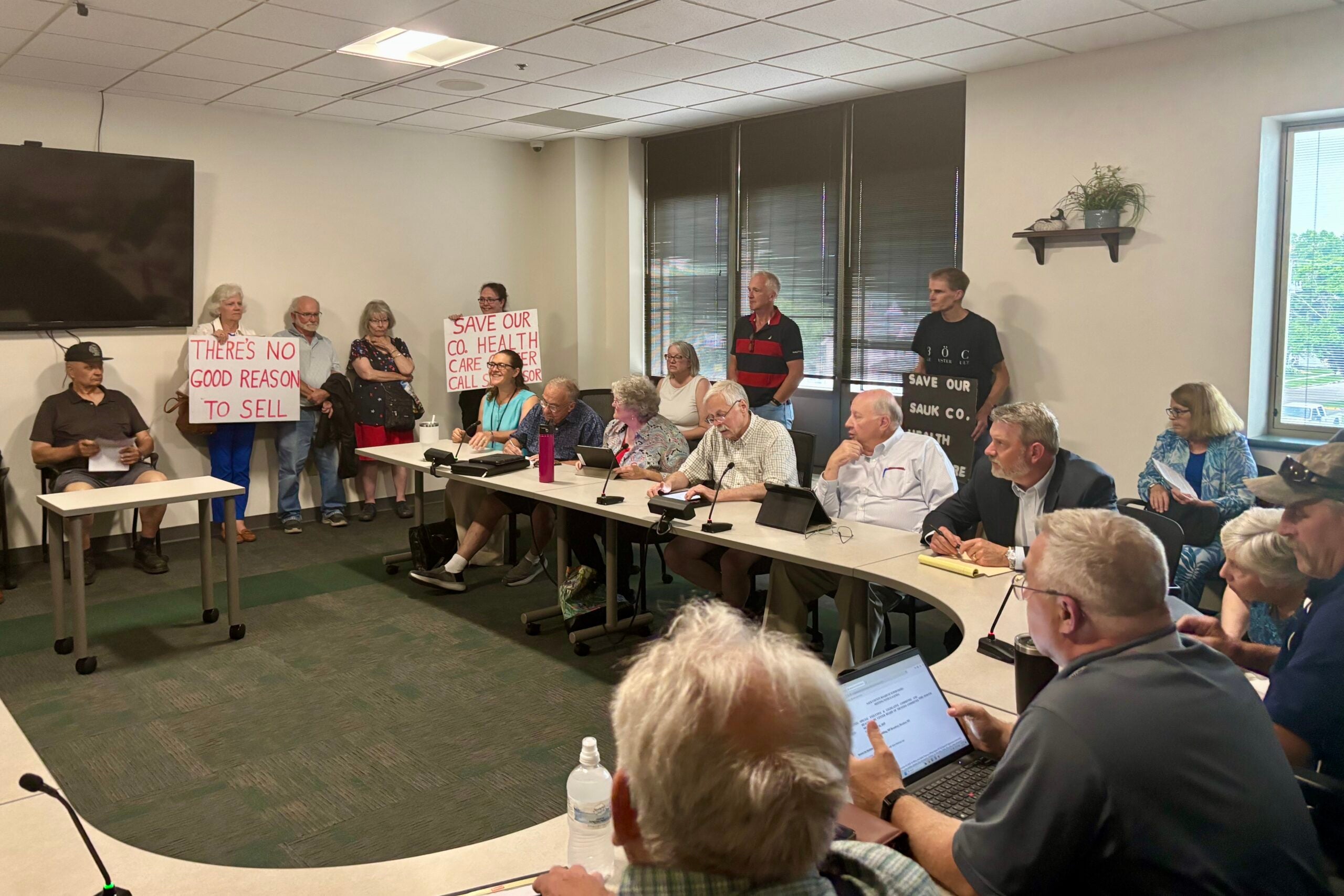

In June, roughly two dozen locals presented a petition with more than 600 signatures to Lincoln County officials, protesting the possible sale. As of July, 68 of Pine Crest’s 83 residents were on Medicaid, according to North Central Health Care, the organization hired by the county to operate the nursing home.

St. Stephen’s United Church of Christ Rev. Michael Southcombe attended the Lincoln County gathering in June. He fears selling the nursing home to a private entity would result in a reduction of Medicaid beds.

“To believe that someone will buy Pine Crest, either a nonprofit or a for-profit entity, and keep the same level of service — with 70 to 80 percent of the residents on Medicaid — is magical thinking,” he said.

Nursing homes usually limit Medicaid patients to about 10 percent of their census, and make up financial losses from them through private-pay residents, Southcombe said.

“That’s financially viable,” he said. “When you’re looking at Pine Crest and other county nursing homes, they are not financially viable unless you have a county government putting money into it or an endowment putting money into it.”

Lincoln County has pledged to keep Pine Crest a skilled nursing facility. But its future ownership remains unclear after the County Board in August voted against a referendum to boost local funding for the facility for the next decade.

Gary Olsen is the executive director of North Central Health Care, the organization hired by the county to manage Pine Crest since 2020. He said the facility would have had a balanced budget last year if not for a decrease in state payments of more than $1 million compared to previous years. Olsen also said the new two-year state budget doesn’t address the issue.

“There isn’t anything else moving forward to make up that shortfall for this year, and the budget did not make up that shortfall,” he said.

Olsen also said staffing shortages have affected Pine Crest’s ability to fill the facility to capacity, which further exacerbates revenue struggles.

“We have 120 beds available,” he said. “Because of staffing issues, we can only staff it at a census of 85. That’s a problem. We have empty beds.”

Advocates say new state budget addresses some issues, but long-term solutions still needed

The 2023-25 state budget did include some provisions that could help nursing homes and assisted living facilities. Senior living advocates said the budget increases Medicaid reimbursement, and includes funding for programs that address the caregiver shortage.

The budget also includes provisions to help address persistent workforce shortages. It allocates an additional $38.4 million in state and federal dollars to the Direct Care Workforce Funding Initiative to help providers supplement employee wages.

Michael Pochowski, president of the Wisconsin Assisted Living Association, said the fund was established to help combat the “caregiver crisis” in long-term care facilities and aims to make their wages more competitive.

“It’s a huge way to recruit and retain caregivers into these very important positions of providing care and services to elderly individuals and those with disabilities all across Wisconsin,” he said of the fund. “With this funding, it’s a huge lifeline for assisted living facilities to recruit and retain caregivers.”

Orheim, of LeadingAge Wisconsin, said the budget continues to fund the WisCaregiver Careers program, which aims to address the shortage of certified nursing assistants, or CNAs.

“That’s a program that basically incentivizes providers and potential CNAs to have CNAs go through this training, where essentially all the costs are covered,” he said. “Then they can go work for long term care providers, and both sides get an incentive for it.”

He also said the staffing issues facing senior living facilities require “longer-term fixes” — such as immigration reform to expand the pool of prospective employees — because “there’s no magic wand to wave to create more workers.”

In looking to the future, Pochowski said providers are also working with the state Department of Health Services on a “rate band” program that would provide more regular inflationary increases to the minimum rates paid to long-term care providers participating in the Medicaid program.

“Nothing has been finalized, at least at this point,” he said. “We’re kind of still in the draft phase of everything.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.