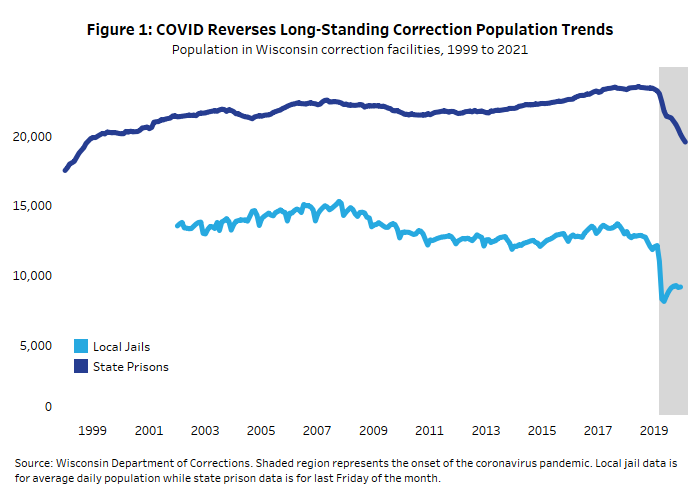

The COVID-19 pandemic caused the inmate population at Wisconsin’s local jails to decline by more than one-third in 2020, according to a new report by the Wisconsin Policy Forum.

In December, for the first time in 20 years, state prisons and local jails held fewer than 30,000 inmates.

Ari Brown, a researcher at the Wisconsin Policy Forum, said it’s unclear if inmate numbers will return to pre-pandemic levels in coming months.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

As more of the state’s population becomes vaccinated, the number of people in custody has increased slightly, but jail populations are still 24 percent lower than they were a year earlier, according to state Department of Corrections (DOC) figures.

“You can really see over the course of the 21st century how consistent the population in jails and prisons have been, especially since the late 1990s,” Brown said. “With this one big event happening, all of the sudden, you see really stark decreases that are happening right away.”

Weekly data from the last Friday in each month showed the adult prison population declined 15.8 percent from the end of February 2020 to February 2021.

Inmate populations at Wisconsin’s county jails dropped faster. From April 2019 to April 2020, the average daily population in the state’s local jails declined by 35 percent.

Over that same time span, 70 of the 71 Wisconsin counties with local jails saw their population decline, including 18 counties that saw declines of 50 percent or more.

In Milwaukee County, which normally has more than double the daily population than anywhere else in the state, saw a decline of 39 percent from a combined 2,120 in its jail and House of Correction in April 2019 to 1,294 in April 2020.

There are several reasons for the decline. An emergency order signed by Gov. Tony Evers in March 2020, put a moratorium on new admissions to state prisons to help stop the spread of COVID-19.

As of mid-February, there remained a backlog of around 1,250 male inmates who were sentenced to prison, who hadn’t yet been transferred from county jails.

In addition, prison admissions are down because court trials have slowed during the pandemic.

Policy changes within the Department of Corrections have resulted in fewer people on extended supervision being revoked and returned to prison.

Within local jails, the Wisconsin Policy Forum found a large number of prisoners were released from in-house detention initially to reduce the population and slow the spread of the virus.

DOC Secretary Kevin Carr said now is the time for the state Legislature to keep working with Evers on continued reform to build on the progress that has been made to lower inmate population.

Evers’ proposed state budget includes an overhaul to the state’s criminal justice system that has several changes to how inmates are sentenced and receive treatment. Republican state lawmakers have said they plan to cut many of the proposals from the bill.

“This administration has noted several times that Wisconsin has taken an incarceration-first approach for too long,” Carr said. “Finding a safe way to right-size the state’s prison population is a priority for us. But the long-term answer to criminal justice reform and lowering the population in the long run will require cooperation from the Legislature. We can do what we can on a policy level, but that only lasts as long as our administration is here.”

Wisconsin’s decrease in inmates is similar to what was experienced at jails and prisons nationwide.

Nicole Gonzalez Van Cleve, an associate sociology professor at Brown University, said people are wondering if prisons and jails are being “decarcerated” too fast. Van Cleve said now is the time to have conversations about prison reform, but she worries there’s too much incentive by many groups, including police unions and politicians, to incarcerate.

“We are seeing nationwide what many activists and the researchers have wanted to try, which is what happens when we reduce the prison and jail population,” Van Cleve said. “We’re not seeing any of those tall-tale fears. My hope is the general public gets the message that we do not have to incarcerate more people to be safer, especially for small, non-violent crimes.”

Jasmine Heiss heads In Our Backyards, a project exploring the shifting geography of mass incarceration at the Brooklyn, N.Y.-based Vera Institute of Justice. Heiss said the pandemic proved it is possible to rapidly decarcerate people. But there are still many individuals getting sick in jail and waiting too long for their trial.

In Brown County, one defendant went 100 days without an attorney.

“It is an unprecedented decline, but it is also totally inadequate to prevent unnecessary deaths and the spread of coronavirus to prison populations,” Heiss said.

The Wisconsin Policy Forum report doesn’t recommend changes to the rate at which people are incarcerated, but does suggest state and local officials could be well served by studying the impacts of the shift from a fiscal and public safety perspective.

Currently, Milwaukee Waukesha, Rock, and Eau Claire counties use a Public Safety Assessment as a pretrial tool to decide whether certain offenders should go to jail or be given a sentencing alternative.

“Nationally and in Wisconsin, corrections has taken up an increasingly large part of budgets. And with all this conversation now about the American Rescue Plan and moving out of the pandemic, it’s going to be an interesting time, and potentially a time to think about where our local and state dollars are allocated,” Brown said.

In 2017, Wisconsin spent $167 per capita on corrections, which was 12.9 percent higher than the nationwide state spending average of $148 per capita, according to the report.

Between 1977 and 2017, local corrections spending in Wisconsin jumped from just $3 per capita to $83, or about six and a half times the increase in inflation over the period.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.