From the time she wakes up in the morning until the time she goes to bed at night, Green Bay parent Denise Seibert’s life centers around her son, Tyler. At just two weeks old, Tyler was diagnosed with fragile X syndrome, a genetic condition that causes a range of developmental problems, including learning disabilities and cognitive impairment.

“I carry a genetic disorder, an autism spectrum genetic disorder, so we had my son tested very early, right after I had him,” Seibert said. “I also have a brother who is a couple years younger than me who has (the same condition). So this has kind of been a lifetime experience with people with disabilities and kind of being in that world and mentality.”

Seibert said because of overworked staff, she has had to take the lead in suggesting services that Tyler needs as spelled out in his individualized education plan, or IEP.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“I believe the district has a lot of good intentions,” she said. “The teachers, paraprofessionals and therapists truly care about the kids and the progress they make each year. But, the staff in the district seem stretched thin. Most of my son’s team is visiting multiple schools every day to see multiple children for services. They all seem overwhelmed with workload and have less time to spend actually working with the kids on IEP goals.”

For parents and teachers, raising and educating a special-needs child can be all-consuming. Parents struggle to care and advocate for their children, who may have significant health, educational and behavior challenges. And teachers face tough working conditions that prompt many of them to switch districts or leave special education, creating a shortage of qualified educators.

Federal and state mandates require that public school districts in Wisconsin provide all of the special education services a student needs. Roughly 14 percent of students in Wisconsin are classified as having special needs, which include physical, intellectual, cognitive, emotional and learning disabilities.

But over the past five decades, state funding support for special education has declined precipitously. That forces districts — which must abide by revenue caps set by the state — to take money from the regular education budget to pay for services they are legally obligated to provide to special ed students.

Last year, the Green Bay School District transferred more than $30 million from the general fund into the special ed fund, said Claudia Henrickson, student services director for the district.

She described it as a “vicious cycle.”

“That is $30 million dollars that didn’t go to the general education students that lowers your class sizes, gives them even more resources, things of that nature,” she said.

Data show that special education staff in Wisconsin have roughly twice the turnover rate of other school staff, and districts report having a hard time filling those jobs. Polling by several disability rights advocacy groups also finds many parents of children with disabilities are dissatisfied with the way their children are educated.

Funding falls short

Meanwhile, special education funding from the state of Wisconsin has dropped over the past half century — hovering around 70 percent reimbursement in the 1970s to under 25 percent in 2018. That leaves an estimated $1 billion for districts to make up through local revenues.

Gov. Tony Evers’ proposed budget called for an increase to 60 percent reimbursement. But the Republican-authored budget he signed in July includes just a 2 percent increase, bringing the reimbursement level to 30 percent by the budget’s second year.

Green Bay Superintendent Steve Murley said some increase is better than no increase, but it doesn’t fix the broken system.

“Anything short of 100 percent funding of special education costs takes money out of our regular education classrooms and pits students and programs against each other,” Murley said. “We already have an annual deficit for which we are required to rob the general fund to pay. That cost is borne by our regular education students.”

Forcing school districts to divert general funds to special education costs “has emerged as a major contributor to inequity in Wisconsin’s school finance system,” according to a 2019 Wisconsin Policy Forum issue brief. Since each district’s share of special ed students varies widely, schools with more special ed students must divert more money from programs that serve the general student population. Those include several northeast Wisconsin districts.

The Menominee Indian School District saw the state’s largest share of unreimbursed special ed costs in 2015-16, according to the Wisconsin Policy Forum: nearly 25 percent of the district’s per pupil revenue limit. The Oshkosh Area, North Fond du Lac and Sturgeon Bay districts also ranked among Wisconsin’s 10 districts with the highest share of special ed costs not covered by the state or federal government.

State spending on special ed low

Across 50 states, there are many different ways special education funding is allocated. A reimbursement system, which is what Wisconsin does, is in the minority. According to the Education Commission of the States, as of 2019, Wisconsin was one of seven states with a reimbursement system.

Among the seven, Wisconsin had the lowest reimbursement rate at 28.18 percent. Some states with such systems, including Wyoming and Rhode Island, reimburse the full cost.

State Rep. Joel Kitchens, R-Sturgeon Bay — who co-chaired the Blue Ribbon Commission on School Funding in 2018-19 — said by law, districts are required to spend whatever is needed to provide services called for in a special ed student’s IEP.

“So when we increase the special ed aid, if we were to put it up to 50 percent, that money actually wouldn’t go to special ed kids, because they are going to get the same amount (based on their IEPs). That is sort of a fallacy of opinion — ‘You are not putting enough into special education, that is hurting special ed kids.’ It’s really not. It’s hurting the overall bottom line. But the special ed kids, (districts) have to spend that amount.”

Nevertheless, Kitchens’ commission recommended a series of options, all of which would increase special education funding. One option called for the state to provide 60 percent of the cost.

Meeting special needs

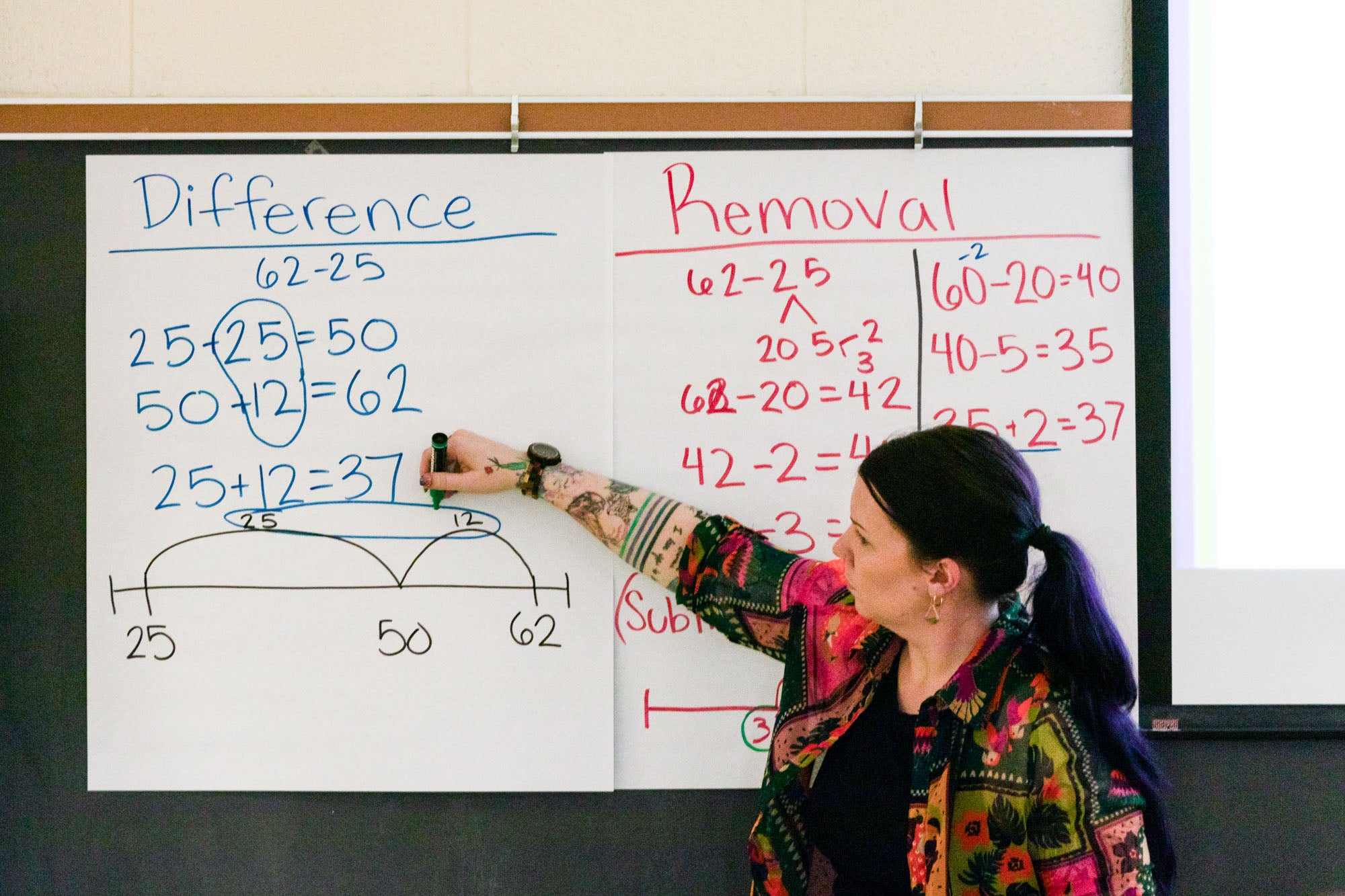

Tammy Nicholson, director of pupil services for the Ashwaubenon School District, said districts begin by placing students in the least restrictive method of delivery, which is in a general education classroom. Students can move into a more collaborative setting, where general education teachers sometimes co-teach with special education teachers or aides.

Students who require additional services may be pulled out of general education classrooms for specialized skill instruction or an alternative curriculum at points throughout the day.

To determine the resources a special education student needs, each student receives an individualized plan for learning, known as an IEP.

Patti Williams, an assistant director of special education at the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, said the 1975 federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, or IDEA, was enacted because students with disabilities were being excluded from public school classrooms.

Not every child with a disability receives an IEP. Students whose needs don’t require services from a special education program, but who still require extra support, instead receive a 504 plan. The plan comes from Section 504 of the 1973 federal Rehabilitation Act, which prohibits discrimination against people who have disabilities and requires students receive accommodating services in the public school environment.

Williams said unlike IDEA, Section 504 gives students accommodating services without specially-designed instruction.

“So if there’s certain accommodations you need, for example, a longer time to take a test or longer time to do particular assignments and things like that, you may be eligible (for a 504),” she said.

And not all districts are prepared to offer services parents believe their children need. Berenice Lopez Sanchez said she often feels frustrated seeing her 6-year-old son Armando, who has autism, struggle with instruction offered only in English in his Green Bay school.

“He already knew Spanish before school, and he responds better in Spanish,” she said. “So if you all of a sudden throw him into English, it’s like starting all over again.”

Education extends to age 21

Samantha Platkowski credits her daughter Hannah’s academic success to her teachers.

“We have had some amazing teachers and staff across grades both special education and in the mainstream setting,” Platkowski said. “They are creative with teaching ideas, open to our ideas and suggestions and really want the students to succeed.”

Hannah Platkowski has Down syndrome and has spent 13 years in Green Bay’s special education program. Although she is 19, because she has special needs, she is by law eligible for services until she is 21. Currently, Hannah is participating in a work experience job through her school at CP, a nonprofit that serves children and adults with disabilities.

“The district provides a job coach that attends with her,” Platkowski said. “It is a paid position that she loves and (she has) gained a lot of usable job skills from.”

Platkowski said out-of-the-box thinking by teachers over the years gave Hannah the extra support she needed to succeed.

“Our daughter entered middle school unable to tie her shoes,” Platkowski said. “When our daughter asked to play basketball, her teacher collaborated with the coach and players, and the players helped Hannah learn to tie her shoes.”

And when she wanted to speak at her graduation, Platkowski said, teachers and staff at Green Bay West helped her write, revise and practice her speech.

High turnover, staff shortages

But Platkowski said she sees a lack of support for special education teachers, whose jobs are uniquely difficult.

“These are jobs that have a high rate of burn out, are high-stress, high-anxiety and take an emotional and sometimes physical toll on the staff members,” Platkowski said.

Jennifer Garceau, Howard-Suamico’s student services director, said her district has a hard time filling openings for teachers and other special ed staff.

“I don’t know the reason why,” Garceau said. “I was a teacher first, a special education teacher.”

Jennifer Kammerud, director of the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction’s educator preparation and licensing department, said districts can apply for one-year emergency licenses for people who are already licensed or who are in the process of receiving a special education license. Kammerud said in recent years there’s been an upward trend in the number of such licenses issued each year.

A Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction report found between 2011-12 and 2017-18, there was a 268 percent increase in the number of special education licenses awarded.

“At the same time, we have more licenses we’re issuing in this area, we also have more students in need of special education services,” Kammerud said.

According to DPI data, the percentage of students with a known disability who require an individualized education plan across Wisconsin has increased from 13.7 percent in 2016-17 to 14.2 percent in 2020-21. At the same time, enrollment counts across the state fell from 863,881 in 2016-17 to 829,935 in 2020-21. As statewide student counts continue to decline, the proportion of students with an IEP among that population has risen.

So if more educators are licensed, why are districts experiencing a shortage of qualified educators?

Some graduates are mismatched by specific programs — for example, they specialized in early childhood education, but there’s a need for high school teachers, or they wish to live in a different community than where the greatest need is, said Jack Jablonski, associate vice president of the University of Wisconsin System office of public affairs.

And the turnover rate for special education staff is higher than for elementary education and other subject areas, according to data from DPI. In the 2015-16 school year, 11.95 percent of special education staff left their jobs for another public school job, compared to 6.75 percent of elementary-level staff. Attrition — leaving the public school system altogether — is also higher for special ed teachers, 9.1 percent compared to 7.1 percent for elementary teachers.

That means one of every five special education teachers switched schools or left the public school system in the 2015-16 school year.

Julia Hartwig, DPI special education assistant director, said retention is also a problem with other professions intertwined with special education. Garceau agreed, saying Howard-Suamico has found it hard to fill positions for school psychologists and speech and language pathologists as well as special ed teachers.

Small victories keep teachers going

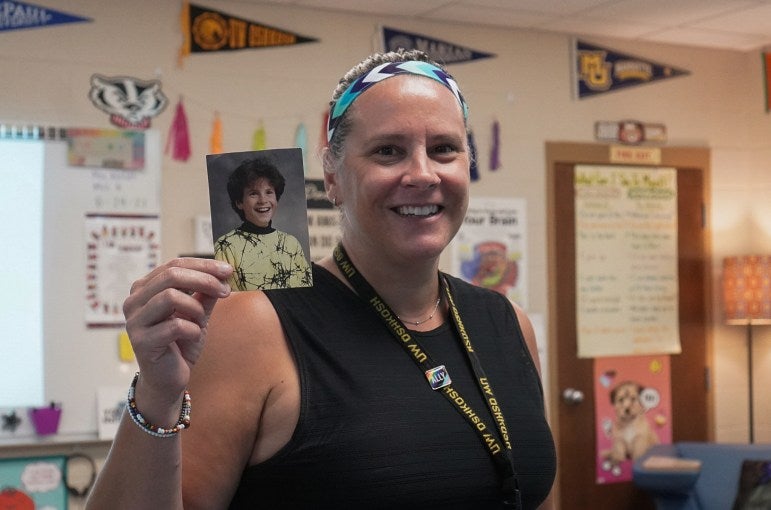

For more than three decades, Stacy Splittgerber has helped Green Bay’s youngest special education students. She is an early childhood teacher at Kennedy Elementary School with children ages 3 to 6 with varying needs.

Splittgerber said student successes keep her motivated — but the job is not easy.

“I can have a really bad couple months, and I can go home and be like, ‘I’m out, this is my last year,’ “she said. “And then there will be a day after that and there is a huge breakthrough with one of the students… It’s in those moments when I know I’ve made a difference. That I know that I need to keep coming back, because they need me.”

Splittgerber said some days are tougher than others.

“I had a little boy — he would just scream at everything,” she said. “So, an hour-and-a-half of my three-hour morning is him screaming continuously. And I would go home those nights and say ‘I can’t do this.’ And then the next day I go in and he runs off the bus and says ‘Stacy, Stacy, I missed you. I love you.’ And so that is the day that I know I have to keep going. There is always a positive for a negative.”

Heather Potts takes a similar approach. At the end of every day, Potts — a fifth-grade math and science teacher at Lineville Intermediate School — takes a moment to scan each desk in her classroom, making note of the successes the students in those seats had that day.

Though she is a general education teacher, Potts said aspects of the special education program have always been a part of her classroom — whether it’s a student with a 504 plan needing accommodations or another special education teacher who joins the class to provide help to students.

“I literally look at each seat and just kind of think about what went well with each student that day,” Potts said. “If I had a really bad interaction — or felt like that challenge didn’t go the way I wanted it to, or it was just a stressful day or that lesson was just a bomb — there are always more positives than negatives.”

Special education teacher Jenny Woldt also teaches at Lineville. She starts each day with breakfast in her classroom with her students.

“We have this really cool community of gathering time, like a dinner table, if you will,” she said. “And it is a great time for us to check in with each other to see how our evenings went — with sleep, with family, with our temperament, just that checkpoint.”

Woldt said she has come to realize, regardless of her efforts, there are some things she can’t fix.

“I can control providing, when students are with me, a stable, calm, safe environment with high expectations, but with high love. I can control that,” she said.

Wisconsin Watch’s Dee J. Hall and Jim Malewitz contributed to this report. The full version of the Press Times’ series on special education can be found at gopresstimes.com. This story was produced by the NEW News Lab, a collaboration of newsrooms that focuses on issues important to Northeast Wisconsin.