On the afternoon of Jan. 25, 2002, Kathy Szeflinski drove down Interstate 43 in Ozaukee County.

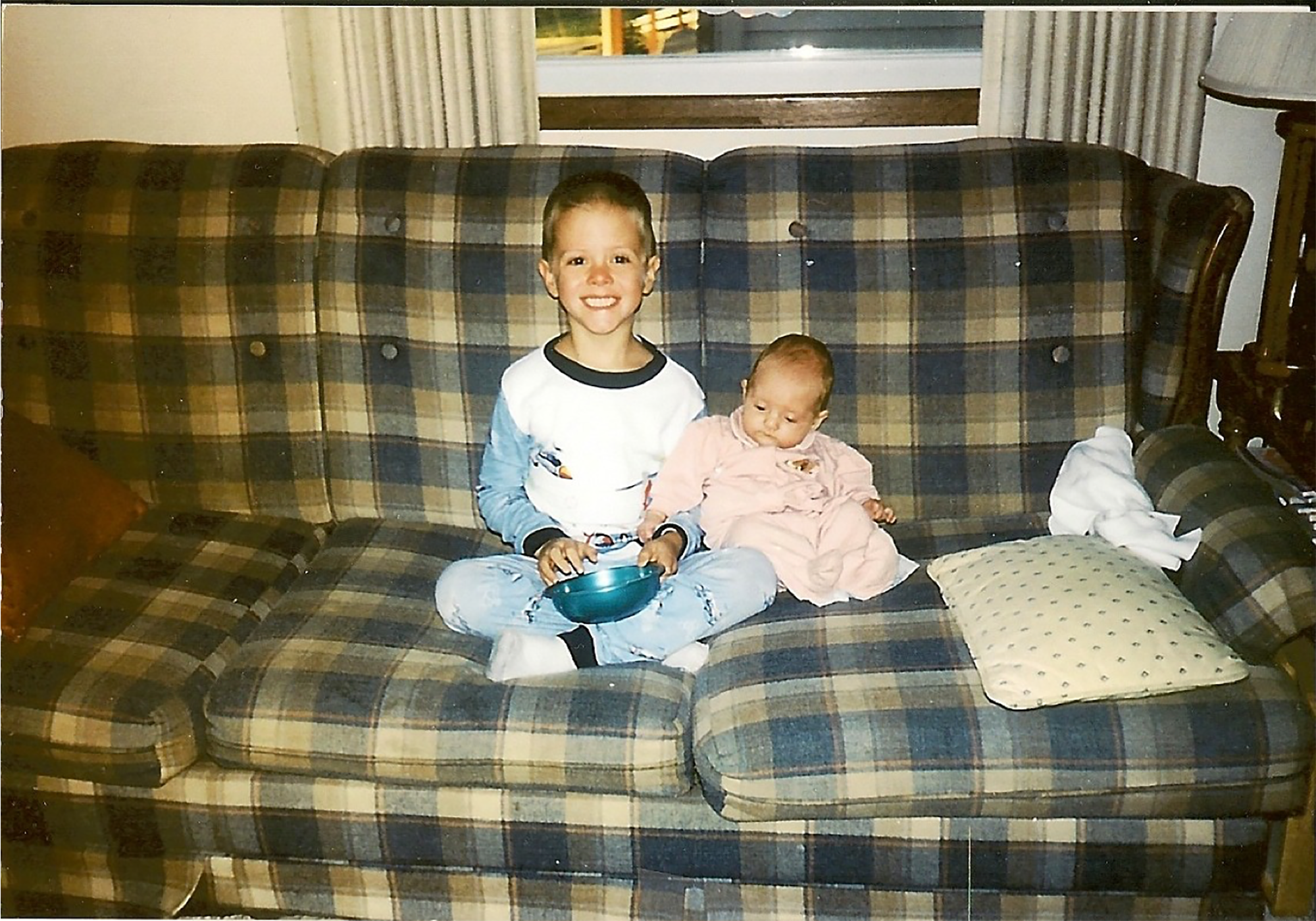

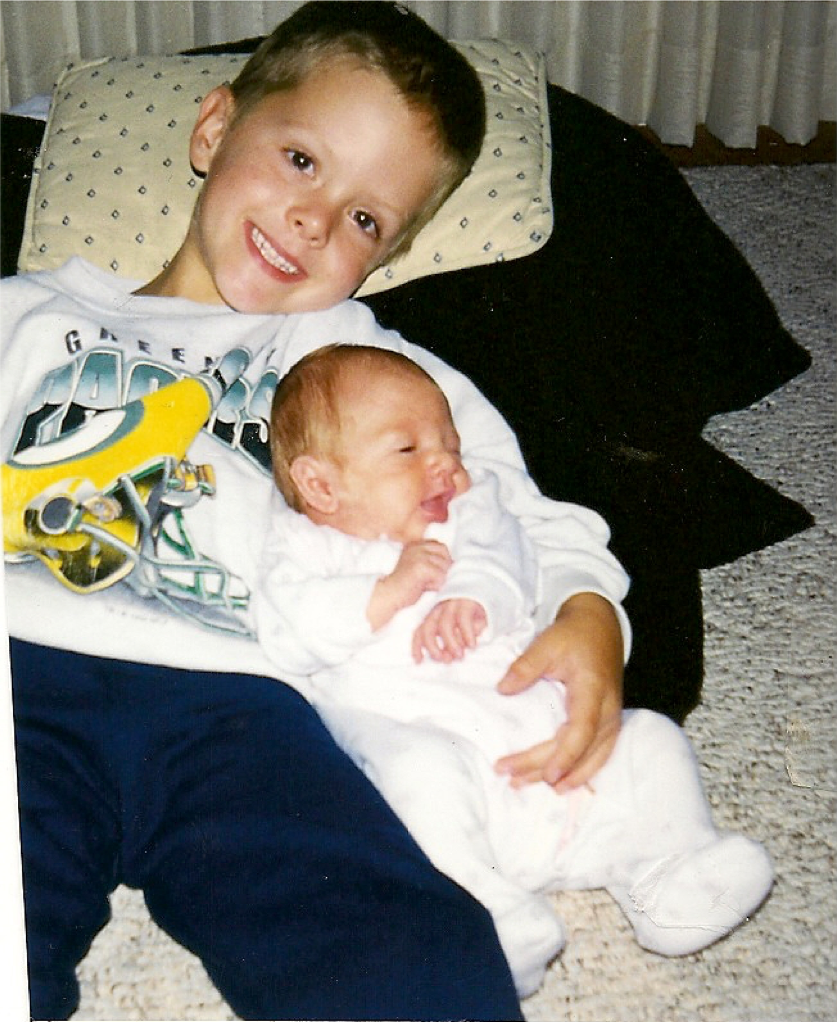

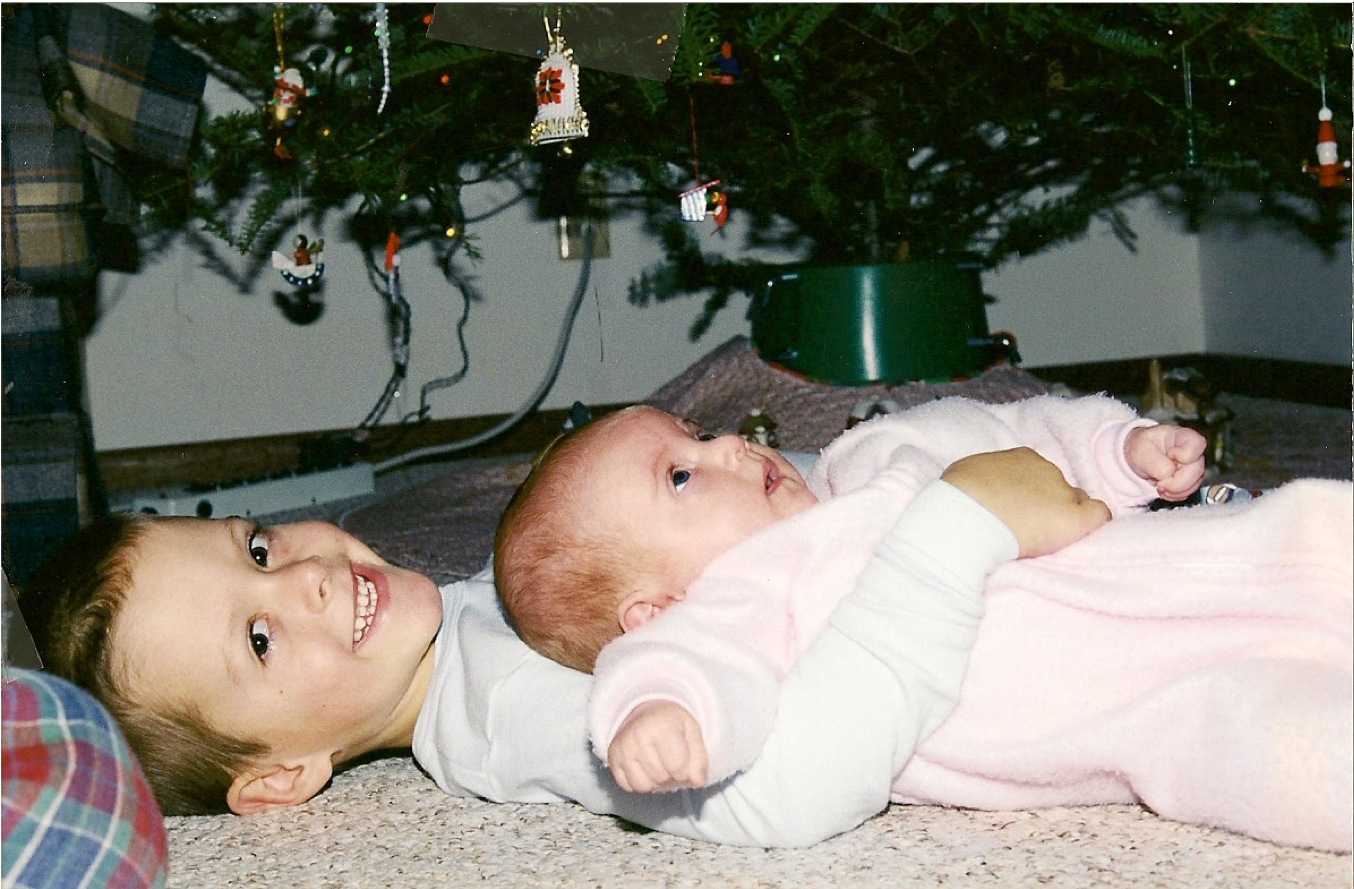

Her 5-month-old daughter, Lauren, dozed in her car seat. Her son Jake, who would turn 5 in two days, counted trucks on the highway until he became drowsy.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

She remembers him saying, “Mom, I think I want to take a snooze. Do you mind if I take a snooze?”

Szeflinski told Jake to nod off, which he did.

“In my head, he was asleep,” Szeflinski said. “And that’s important to me because he couldn’t see what was coming.”

Szeflinski’s family of four would become a family of two by the end of the day.

Earlier that morning, she’d taken Jake to his five-year checkup.

“We were getting ready to go and I said, ‘Who do you want to take you?’ And he said, ‘Well, why don’t we all just go as a family?’ Like, you know, how sweet is that?” the mother recalled.

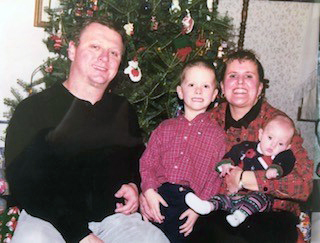

So they went together: Szeflinski, her husband Bill, Jake and baby Lauren.

Kathy remembers holding Jake — lanky-legged and sniffling — in her arms as he got a few shots.

Afterward, Kathy dropped her husband off at home before taking the children to her friend’s house for lunch in Port Washington. Kathy said Jake seemed disappointed to see his dad go, and held up his hand in a still, sad wave.

“Thank goodness we did” drop Bill off, Kathy said. “Because one of us wouldn’t be here.”

On the drive back from Port Washington to their home in South Milwaukee, Kathy looked in the rearview mirror. She saw Jake, sitting on the passenger side next to Lauren’s backward-facing car seat, close his eyes, nodding off to sleep like his baby sister.

Up ahead, Kathy saw a car driving toward her. It was in the median. Then, it was in her lane.

She realized she couldn’t merge right. She thought: “Do I stop? Do I play chicken? What do I do?”

She turned into the ditch, into — she thought — safety. But the other car swerved back into the median. It T-boned Kathy‘s car, on the passenger side.

The driver, Wallace Stenzel, had two martinis that afternoon. His blood alcohol was 0.10, just over Wisconsin’s legal limit of 0.08.

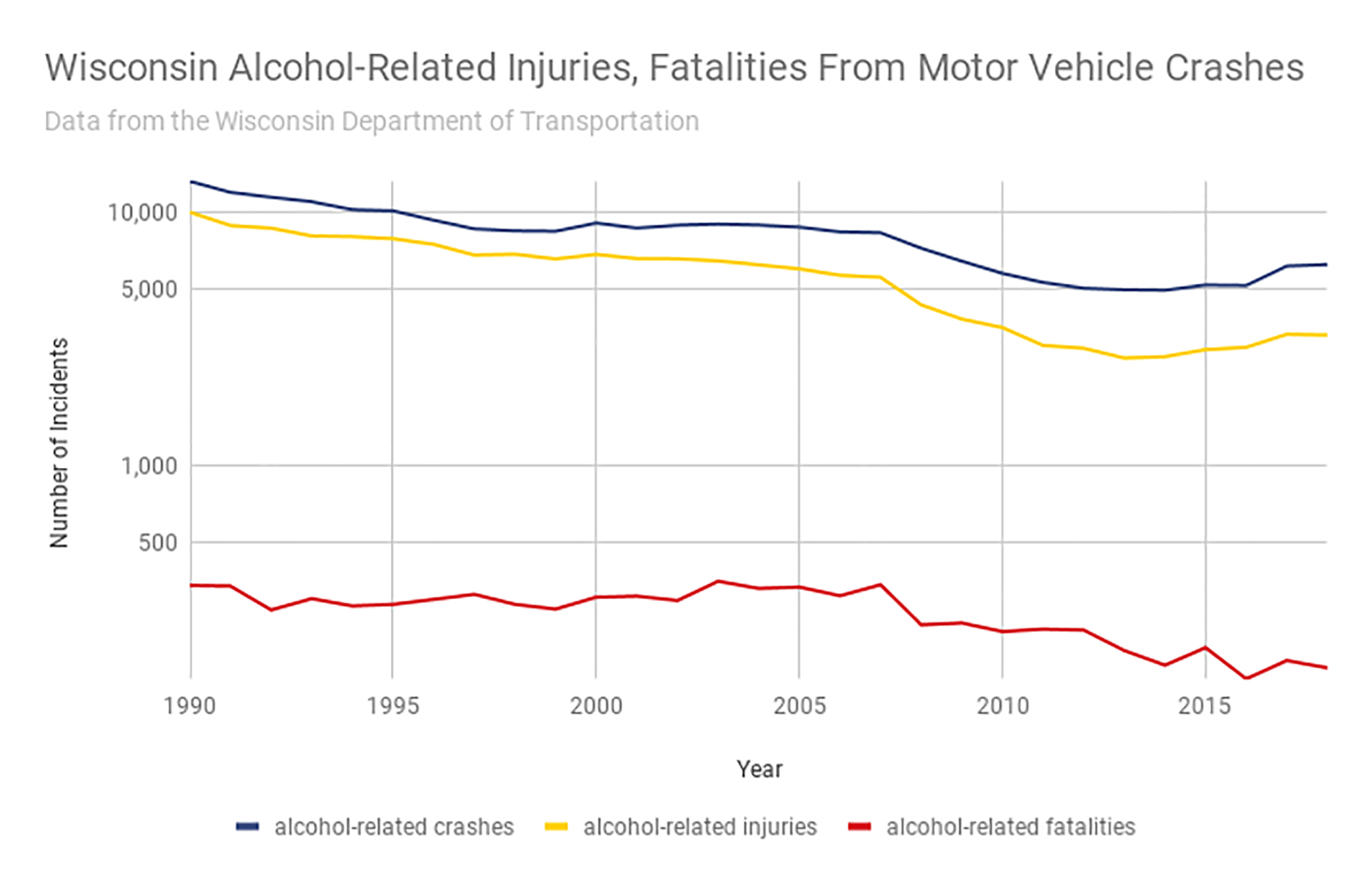

By the end of that year, 8,992 alcohol-related crashes would occur in Wisconsin, injuring 6,570 and killing 292, according to the state Department of Transportation.

‘He Didn’t Suffer’

An ambulance took Jake to Columbia St. Mary’s Hospital in Ozaukee. Kathy followed in another ambulance with Lauren. She said the ambulance driver told her to decide whether she wanted to donate her children’s organs.

“That’s when I knew it wasn’t good,” Kathy said.

At the hospital, she found Jake lying on a table, wearing one shoe, his hand ice-cold.

The doctor told her Jake died instantly. When Bill arrived, she didn’t know what to say.

“I felt helpless. I said to him, ‘He didn’t suffer,’” she said.

In another room, doctors decided to transfer Lauren to the children’s hospital. Bill stayed with Jake and Kathy went with Lauren in the helicopter.

“As we’re flying over the city, all I could think of is, ‘Jake would love to be in this helicopter for the right reasons,’” Kathy said.

When they landed, Lauren was rushed in for another procedure. But eventually, doctors said it wasn’t working and they asked if Kathy wanted to be with Lauren while she died.

Kathy remembers the room as a sea of yellow and blue scrubs, the life-supporting machines beeping rhythmically.

“No one was saying a word,” she said. She could see the hospital staff’s eyes above their masks: “Just sadness.”

A nurse then stepped out of the crowd.

“She said, ‘You know, it’s OK. Come on up. She can hear you. Talk to her,’” Kathy said. “And I did. I would always rub her little head and then I was holding her hand and rubbing her head, and I said, ‘It’s OK, Lauren. I’m sorry I couldn’t save you. Go home and be with your brother.’”

The beeping stopped.

To Kathy, Lauren looked like a porcelain doll.

“She was perfect, but her little brain was all shook up,” Kathy said. “I’m holding my little baby daughter, and she’s dead, she felt like 100 pounds.”

Kathy’s husband Bill arrived and Kathy simply asked if he’d like to hold her.

“And of course, he cried and sat down and held her and rocked her,” she said.

I was holding her hand and rubbing her head, and I said, ‘It’s OK, Lauren. I’m sorry I couldn’t save you. Go home and be with your brother.’

Stenzel, the man who killed the two children, eventually served eight years in prison for two felony counts of homicide by intoxicated use of a motor vehicle.

He died a year after his release, at age 87. Kathy said Stenzel never told her he was sorry.

Sometimes, Kathy has to remind herself that her children died 17 years ago.

“To me, it was like yesterday, and it just — it’s endless,” she said.

Today, Jake would have been 22 and Lauren would have been 17.

Kathy said she and her husband have struggled with depression and suicidal thoughts.

But she also said they made a choice: to figure out how to keep living. The mother sought therapy, took anti-depressants and went to church.

“I believe I’m going to see them again and they’re with their Heavenly Father,” Kathy said. “I pray for peace, and understanding, and guidance. I don’t know, if I didn’t have that, how I would be able to go on to the next day.”

Kathy said she’s experienced miracles after the crash — mainly, her children.

Kathy and Bill decided to have more children a few years after Jake and Lauren died, this time through in vitro fertilization. The doctor’s third attempt at retrieving and fertilizing Kathy’s eggs happened on the anniversary of the crash. Every embryo implanted took.

She gave birth to twins: a boy and a girl, named Tommy and Andrea.

Every year, the family celebrates Jake and Lauren’s birthdays with tacos. On the anniversary of the crash, the Szeflinskis get together with friends and relatives to celebrate and remember Jake, Lauren and other loved ones who have died.

Sharing The Impact

Almost every month, as she has for over a decade, Kathy shares the story of the worst day of her life — the story of her children’s deaths — with drunken-driving offenders.

She speaks onimpact panels around Milwaukee, Kenosha and Racine counties. She said she doesn’t know why she does it, but something compels her.

“I don’t know if the impact panels help, because what can I possibly say?” Kathy said. “I just want them to make the right choices.”

In the United States, the average person arrested for drunken driving has driven drunk over 80 times before his or her first arrest, according to Mothers Against Drunk Driving, a national organization that doesn’t have an affiliate office in Wisconsin.

Some of those offenders are sent to impact panels, such as those Kathy speaks on.

In Wisconsin, specific attendance requirements and formats vary by county, but the purpose remains the same: impaired driving offenders — whether under the influence of alcohol or other drugs — listen to the stories of those affected by such action.

Often, the speakers have lost loved ones to drunken driving, such as the Szeflinski family. Sometimes, they themselves have killed or injured someone due to impaired driving.

Academic studies into the successfulness of victim impact panels have shown mixed results. One study from 2001 even suggested they might have negative consequences on female repeat offenders.

Guida Brown, executive director of the Hope Council on Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse, organizes the panels in Kenosha County, where every person stopped by police for impaired driving must attend one.

Brown acknowledges the lack of evidence supporting the panels’ effectiveness, but said she chooses to hold them anyway because she believes they provide a powerful experience, especially because the majority of drivers who kill or injure someone while driving drunk have no prior convictions.

“It’s really important for offenders to see that what they’re doing makes a difference, what they’re doing could take a life,” Brown said. “Nobody thinks they’re going to be the person who kills somebody.”

An order sheet for the Dane County Circuit Court victim impact panel reads: “The goal of the victim impact panel is not to blame or judge offenders in the audience, but to reach the audience on an emotional level … a level that courts, fines and jail may not be able to reach.”

They ultimately intend to reduce the number of deaths and injuries from alcohol-related crashes.

Dane County’s spring victim impact panel took place March 21 in downtown Madison. Attendees arrived alone or in pairs. They presented their IDs and signed in, passed two uniformed police officers and took their seats in the auditorium.

Julie Foley, who works in victim services in the county’s district attorney’s office, addressed the crowd of a few dozen.

“In my job, the cases that are the most difficult, the most senseless, the most devastating and the most preventable are crimes that involve impaired driving,” Foley said.

She then introduced the evening’s two speakers, both mothers who had lost their sons.

A woman identified as Cindy lost her 25-year-old son, Dave, to a drunken driver in 2003. A woman named Kelly survived a serious crash in 2000, but her unborn son didn’t. Kelly remains physically disabled.

Before Cindy talked about her son’s death, she asked for the audience’s attention.

“It’s very difficult for us to come here and have to relive the day that our accidents happened,” Cindy said. “It’s even more difficult to stand in front of a crowd that really does not want to be here.”

Cindy stood in the center of the stage and spoke without notes or a microphone, in a strong voice that sometimes wavered with anger and sadness. She talked about how Dave loved music, and how she learned how to play his instrument, the electric bass, as a tribute to his life and legacy.

If I told you that I never drank and drove before this accident, I’d be a liar. If I told you I probably wasn’t sometimes way too drunk to drive, I’d be a liar. I grew up in Wisconsin. I know how we view drinking and driving here.

When Kelly took the podium, she closed her eyes and took a deep breath.

She talked about being struck in a head-on collision by a businessman who had gone to a University of Wisconsin-Madison Badgers football game earlier that day. Kelly had one more class before she finished her bachelor’s degree atUW-Madison. The day she was hit head-on was her 24th birthday. She was just married. She was eight-and-a-half months pregnant.

Kelly’s right leg was shattered. Her unborn-son, Dean, didn’t survive the crash.

Had Dean been born on that day under any other circumstances, Kelly said he would have lived. He had fully developed lungs. He weighed 6 pounds and was 19.5 inches long.

“You don’t know how old they’re going to be when they walk. You don’t know what kind of person they’re going to grow up to be. You don’t get to know any of that,” Kelly said. “Every moment of his life was taken from his family because of somebody else’s decisions.”

In the two decades since her crash, Kelly has learned to walk again. She graduated college. She had more children. She received her master’s in addiction studies.

Kelly now works as an addiction counselor and manager for a treatment center in northwestern Wisconsin.

Kelly doesn’t know whether the person who hit her was an alcoholic, she said.

“But I do know that his drinking ruined his life and it changed mine and everybody that knows me permanently,” Kelly said.

For the last 15 years, Kelly has helped people in Wisconsin recover from addiction — while she, too, heals from damage done by alcohol.

“If I told you that I never drank and drove before this accident, I’d be a liar. If I told you I probably wasn’t sometimes way too drunk to drive, I’d be a liar,” she said. “I grew up in Wisconsin. I know how we view drinking and driving here.”

But she also knows what can happen.

Photo courtesy of Szeflinski family

Photo courtesy of Szeflinski family

Photo courtesy of Szeflinski family

Photo courtesy of Szeflinski family

Photo courtesy of Szeflinski family

Photo courtesy of Szeflinski family

Banding Together To Eliminate Drunken Driving

When Marla Hall, of Waterloo, lost her son to a drunken driving crash, she decided to take action.

Hall’s only son, Clenton, was killed by a drunken driver on Nov. 2, 2016 on Interstate 94 by a repeat drunken driver. Katey Pasqualini, Clenton’s fiance and co-worker, and co-workers Kim Radtke and Patrick Wasielewski were also killed. The driver of their vehicle, Brian Falk, somehow survived.

The driver who struck the group survived with serious injuries.

As Hall grieved, she researched. She said she was “appalled” by Wisconsin’s laws around drinking and driving, as well as the number of repeat offenders.

Eventually, she founded the advocacy group Eliminate Drunk Driving, which has become the most visible group in Wisconsin fighting to improve drunken driving laws.

Hall testifies before lawmakers at the state Capitol every chance she gets, sharing her story and advocating for reforms such as ignition interlocks for offenders.

She’s made herself and her mission known, and she’s become a source of inspiration and support for others in Wisconsin who have lost loved ones to drunken driving.

Donna Rosol Johnson, of Lake Geneva, connected with Hall after Johnson’s father and family friend died in a drunken driving crash. Johnson found videos of Hall testifying online.

“I was just amazed at how much strength she had and conviction,” Johnson said. “She stayed so calm and direct that I was like, ‘I have to meet this woman.’”

Johnson became a member of Eliminate Drunk Driving, and helps out however she can.

“I do anything that she asks,” Johnson said of Hall.

On March 19, members of Eliminate Drunk Driving gathered in Madison to meet with lawmakers as part of a day organized by Mothers Against Drunk Driving. March 19 was, they knew, the same as the Tavern League of Wisconsin’s legislative day.

“I lost my baby and he was the world to me,” Hall said at a press conference that day with state Rep. Jim Ott, a Republican from Mequon, and state Sen. Chris Larson, a Democrat from Milwaukee. “It’s hard to go on, but I’m going to keep up this fight because I’m doing it for them.”

Eliminate Drunk Driving has several legislative goals: to make a first-offense operating while intoxicated a crime, to install ignition interlocks for all offenders, to implement sober server laws, to expand the number of wrong-way detection devices and to establish sobriety checkpoints.

“Drinking and driving should not be our culture,” Hall said.

A Strong, Statewide Influence

Addiction is widely recognized as a disease, but Wisconsin’s drinking culture is potent.

City groundbreakings and baby showers serve kegs. Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett, Gov. Tony Evers and others drank beers at the contract signing for the Democratic National Convention.

“Wisconsin has a very complicated relationship with alcohol and with drinking and driving,” said Foley, of victim services at the Dane County victim impact panel.

Wisconsin is, after all, the only state that classifies first-time drunken driving as a civil offense.

It’s led some treatment organizations to call out the problem by name.

IMPACT, a Milwaukee-based agency that serves southeastern Wisconsin, has a campaign called “Stop Drinking So Much, Wisconsin.”

John Hyatt, IMPACT’s president and CEO, said the state’s drinking culture is generational and ingrained. He’s trying to raise awareness about the amount and frequency of alcohol consumption that puts people at risk, whether for addiction, health issues or injuries.

Five drinks in a single sitting for men and four drinks for women constitutes binge drinking, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Women who consume three alcoholic drinks per week have a 15 percent higher risk of breast cancer — and the risk increases by 10 percent for each additional drink women have each day — compared to women who don’t.

“I just don’t think that, particularly in Wisconsin, we have a sense of how much drinking is too much drinking,” said the Hope Council’s Brown. “With alcohol, we think it’s not a problem because it’s legal, and we talk about it all the time and we make jokes about it.”

Kathy Szeflinski, who lost her children, Jake and Lauren, in a drunken driving crash, grew up in Wisconsin. She said she comes from a family of alcoholics. Her father worked in a bar and, she said, drank himself to death. Her brother served several years in prison for drunken driving, after Jake and Lauren’s death.

“You would think that the death of Jake and Lauren would stop someone, somebody, my family,” Kathy said. “The night of the crash my dad and my brother were drunk in my basement and I’m sure one of them, if not both of them, drove home.”

Kathy refuses to call her collision an accident. She said it was entirely preventable.

“How do you kill these cute little kids?” she said, referencing Wallace Stenzel. “I know you didn’t mean to, but again, you had two drinks and it cost them their lives.”

Jake and Lauren were just two of 292 people killed in alcohol-related crashes in Wisconsin in 2002. More than 4,000 people have died and 70,000 people have been injured since, according to the DOT.