Cuban refugees reconcile with racist encounters, criminal pasts and the path forward

By: Maureen McCollum, Omar Granados

Episodio 7: traducción al español próximamente

Editor’s note: This episode contains mentions of violence and language that may be inappropriate.

In 1982, it had been two years since Osvaldo Durruthy and thousands of other Cuban refugees arrived in the United States following the Mariel Boatflit.

Two years since Durruthy made a harrowing journey across the Florida Straits. Two years after he was briskly shipped off to Wisconsin, one of almost 15,000 Cubans sent to live in military barracks at Fort McCoy. Two years since he joined a band at the camp as a dancer and bongo player.

In 1982, all that seemed behind Durruthy. He had just settled in Madison and had a girlfriend.

“We were sharing an apartment,” Durruthy said. “And we were going to (the) disco, you know, having fun, buying things, singing, dancing.”

One of their favorite discos was a State Street nightclub called Merlyn’s. One night, they were hanging out with a group of friends, sitting in a booth, having some drinks. Suddenly, the ex-boyfriend of Durruthy’s girlfriend walked in. He was furious that she was now dating Durruthy and confronted their table.

Durruthy told him to talk to his girlfriend the next day instead. But the ex-boyfriend returned 10 minutes later. He had been threatening the life of Durruthy’s girlfriend for two weeks and in that moment, it seemed like he might to carry out his threats.

The ex-boyfriend came at Durruthy’s girlfriend. In response, Durruthy grabbed a big, heavy, glass ashtray off the table.

“I grab it and I hit him in the face. Pow! And he (falls). And I look and I turn around and I sit on my table like nothing happened,” he recalled.

People warned Durruthy to watch himself. The ex-boyfriend had gotten back up, and he had a gun.

“He was pointing a gun on me,” Durruthy said. “He said, ‘I will kill you and her, both.’ I said, ‘Man, put it down. Man, don’t do that. You don’t want to kill nobody.’ And I … (grabbed a) chair. And I went toward him with the chair. He got in my face. And (the) first shot … went through the chair and got me here.”

Durruthy pointed to the left side of his face, where he was shot in the jaw. Then he pointed to his forearm. The gunman also hit Durruthy in his leg and his chest.

But despite being shot four times, Durruthy wrestled the man to the ground, just as a bunch of other Cubans jumped to his defense.

“They beat the hell out of him and they took the gun from him, and they put it in my hands. I was on top, they said, ‘Kill him!’ … And I tried to pull the trigger, (but there were) no more bullets,” Durruthy said. “So I fall on top of him, and then we both went to the hospital in the same ambulance. He got beat up so bad.”

The Mariel refugees have all been through challenges. Some have made bad decisions. They’ve all faced discrimination. And all of them have tried to move forward as their pasts continue to haunt them.

But not all have of them have gone through what Durruthy has.

Durruthy’s own choices would lead to a lengthy prison stay, and even a run-in with the serial murderer Jeffrey Dahmer.

‘Our past (has) been destroyed by us’

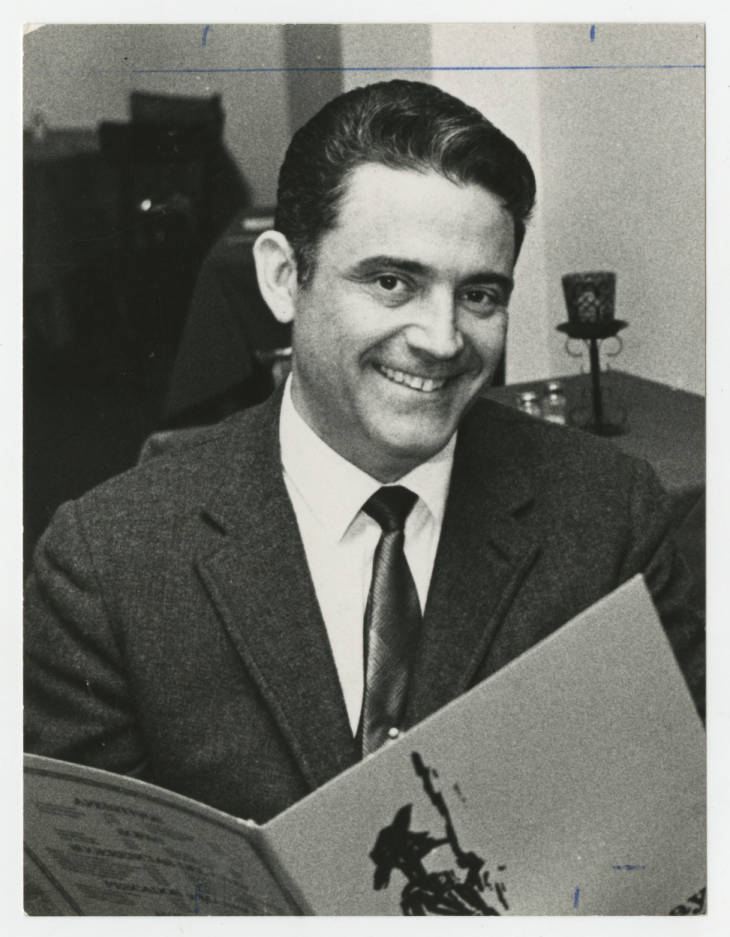

Today, Durruthy’s two-bedroom apartment in Madison is tidy and clean. The walls are plastered with framed degrees and work certificates, as well as family photos from Cuba.

Durruthy takes a break from cooking congri, a traditional Cuban dish, to go through these photos of his mother, grandchildren and sister.

He hasn’t seen his sister in person since he left Cuba in 1980. More than anything, he wants to go back and visit her, but legally, he can’t. His criminal record prevents it.

“Our past (has) been destroyed by us. Nothing, nothing good (is in) our past,” he said.

Most of the Cubans sent to Fort McCoy in Sparta found sponsors and got out. Not Durruthy.

When Fort McCoy closed to refugees in late 1980, he and about 3,200 Mariel refugees were still trying to find sponsors. They were sent to live at Fort Chaffee in Arkansas.

Durruthy doesn’t talk much about his time there — except for how he finally got sponsored as part of a group of musicians and dancers. He said Fort Chaffee officials told the group the sponsor was a Cuban millionaire, José Quintana, in Nashville, Tennessee.

While on the way to Tennessee by bus, the refugees got into a fight, Durruthy said. They had to stay in a motel, and caught word that the Ku Klux Klan was waiting for them outside.

“We opened a window and you could see, you know, (the KKK) all suited up and ready to fight. So we started lobbing sticks on the table and we go outside and whoop their ass. By the time (the) police came in, about three or four of them were in the hospital,” Durruthy said.

The police didn’t take any of the Cuban refugees to jail, Durruthy said.

By morning, Durruthy and his fellow musicians were back on the road and made it to Nashville, their new home.

Quintana provided housing for them and put them to work right away. Durruthy was now a bricklayer, helping build the Opryland Resort.

Durruthy said he earned his wage and saved money for months, then decided to move to Madison. Durruthy fell in love with Madison when he was in the band at Fort McCoy. They traveled around the area performing for people, and one gig was at the Capitol at the top of State Street.

“What I like about Madison — the people … I don’t know why, but they are different,” he said.

He left Nashville at age 21 with a few of his Cuban buddies and moved in with a friend in Madison in 1981.

Getting back into the social scene was the easy part. Durruthy could go out to the clubs, dance and meet a lot of women.

But making money was harder. The support he was getting from the government wasn’t enough.

“When we came here, they (gave) us (a) $200 check a month and $80 food stamps,” Durruthy said.

He didn’t know English very well yet, like many Cuban refugees. When they spoke Spanish in public, they faced discrimination from people in the city who thought Cubans were dangerous.

“It was hard for us, you know, especially communicating, because…every time we (spoke), people (were) laughing, ‘Ah, get out, get out of here,’” Durruthy said.

Divides in culture and communication

Ernesto Rodriguez of La Crosse had a similar experience. He was at Fort McCoy the summer of 1980 following the Mariel Boatlift. He found a caring family to sponsor him in Sparta. And, like many young Wisconsinites, he’d go to the bars.

“(We would) have a drink, play pool there and then dance. And then some girl says, ‘Get closer.’ … It’s a good close, you know. And then sometimes, the boyfriend comes. I didn’t know they (had) a boyfriend! If she told me, I (would) leave her alone,” Rodriguez said.

A handful of the refugees have similar stories. These situations — involving a mix of flirting, alcohol and racism — made them easy targets for altercations and fights.

“Every time we (spoke), people (were) laughing, ‘Ah, get out, get out of here.’”

Osvaldo Durruthy

“We don’t want to fight. We want to have a good time. You know, we don’t have a good time in Cuba because (we weren’t allowed) to have a good time. And the only time you have a good time was when you were little and you go to (a) quinceñera,” Rodriguez said.

Young people in Cuba were expected to work, said Omar Granados, associate professor of Spanish and Latin American studies at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse and co-host of “Uprooted.”

And then here they were, in their early 20s, the first time with money in their pocket, buying beers at a bar. Women were interested in them. And that created problems for them, Granados added.

Rodriguez remembers one man in particular who used to threaten him and his friends at a Sparta pool hall. The man would look through the window from inside a bar and take a stick to mimic a gun toward Rodriguez and his Cuban friends.

Rodriguez’s sponsor mother, Annette Brandstetter, encouraged him to stay out of trouble.

“I took the advice from mom because she told me, ‘Look, anytime you get in trouble, you’re going to pay money. But if you walk away, you’re not gonna pay no money,’” Rodriguez said. “Because anytime I go to court, $100, $200 for (something that’s) not my fault. The people bother me. I’m drinking and they kind of push me, (say), ‘Get out of here, n-word, you (don’t) belong here, you go to where you came from.”

These fights were happening for a few reasons — mostly racism, Granados said. There weren’t many Black people who lived in Sparta.

Marcos Calderón, who also lives in La Crosse and was at Fort McCoy with Durruthy and Rodriguez in 1980, said that was obvious to him right away.

“(There) weren’t that many colored people in any area, you know, except for Fort McCoy and people from the Army,” he said. “And people were not very happy to have us there because (of) the crime that happened.”

This racism wasn’t just limited to small town Wisconsin, either. Mariel refugees experienced prejudice almost everywhere they went, even from the Cuban American community in places like south Florida.

“We don’t want to fight. We want to have a good time. … We don’t have a good time in Cuba because (we weren’t allowed) to have a good time.”

Ernesto Rodriguez

It was difficult for the Mariel refugees to fit in. They don’t consider themselves Latino or African American — and they needed to learn how to be both Black and Latino in the U.S., like a racial reconfiguration, Granados said.

Calderón could see the divides in culture and communication playing out all around him.

“It was the mess-up of communication because … we don’t know English, and we don’t know a lot of things,” Calderón said.

“When I first saw people give me the (middle finger), I said, ‘Hey, hi!’ Because I didn’t know what (it meant). Later I found out, and I say, ‘OK, what did I (do) to you to do that?’” he continued.

Serious crime

There were other cultural divides that had a more serious effect.

There’s the reality that some refugees were found guilty of committing thefts or assaults or getting in fights, but there was also this unfair stereotype attached to all the refugees.

Granados said by March 1981, about five months after the last Mariel refugees left Fort McCoy, there were 400 complaints involving Cubans in La Crosse, according to court cases and police reports. Courts in the area had processed 55 Cuban refugees by that time.

According to reports, these crimes mostly consisted of trespassing, theft, driving without a license, miscommunication with officers and parole violations.

But there were some higher-profile crimes, like when a Cuban refugee stabbed and killed another Cuban refugee — his friend — on the Capitol Square in Madison.

In Madison and La Crosse, there were a number of sexual assaults, bar fights, shoplifting and stalking cases, Granados noted.

In La Crosse, there was a lawyer, Kathleen Mann, who was defending many of the Cubans. She was one of the few lawyers in the area who knew Spanish.

She worked with a Cuban refugee who made national news. In September 1980, 17-year-old Mariel refugee Lene Cespedes-Torres was charged with murdering his sponsor, Berniece Taylor, of Tomah.

He has maintained his innocence and even requested deportation to Cuba. This incident rocked the community and contributed to distrust and resentment toward the refugees.

There were limited resources for these refugees to understand federal and local laws. Things that were acceptable in Cuba could result in arrests in the U.S., like carrying a knife, accidentally trespassing or not understanding police officials when they confronted Cubans, Granados said.

In a place like Miami at this time, there was a community infrastructure in place for Cuban refugees. Cuban Americans could tell the new refugees what they should and shouldn’t do.

But in a place like Sparta, the refugees and Wisconsinites living in the town were both navigating this kind of relationship for the first time.

There was also the issue of Cuban refugees not knowing social rules for flirting and dating in the U.S.

A Wisconsin State Journal story from 1990 says Madison police put together a booklet to help the men understand different social rules, like not to whistle at women or comment on them as they walked by.

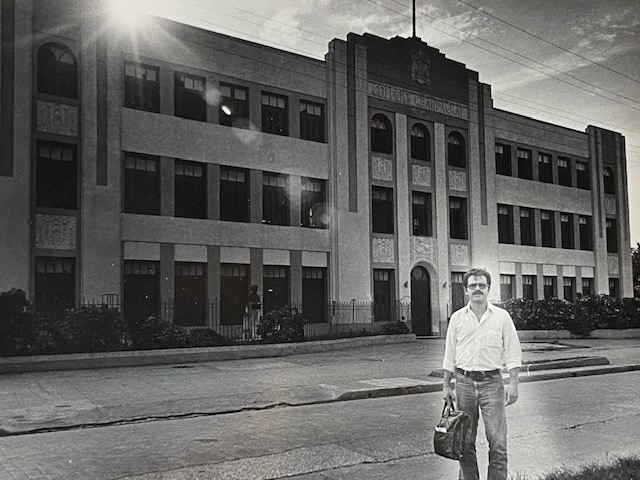

Ricardo Gonzalez of Madison sponsored a number of Mariel refugees to get them out of Fort McCoy in 1980. Many Cubans flocked to his business, the Cardinal Bar, after settling down in Madison.

“Because the Cardinal Bar was the hip place — the music, the women — and that caused me a lot of grief there, because the women didn’t like it (unwanted attention),” Gonzalez said.

“These Cubans, culturally, were very different. You know, the women of Madison, the young women who come to the Cardinal, were pretty free in their attitudes and, you know, liberated women. But these guys thought that that meant … that they could be had,” Gonzalez continued. “And so, there were issues there. Not so much violence, although there were some fights.”

Gonzalez noted that in the spring of 1981, the Dane County jail had a capacity for about 230 people and around 80 of them were Cubans.

These instances put Gonzalez in a tricky position, and it weighed on him. He started distancing himself from the Mariel community.

A handful of troublemakers gave the Mariel refugees a bad reputation, which impacted how the community perceived and welcomed the refugees.

Regardless of how much trouble one of these refugees was getting into, it was difficult for them to find housing and jobs. Some discovered other ways to make money, and those choices still affect their lives to this day.

Drug convictions

Mariel exiles had to make ends meet somehow. Some turned to drug dealing and stealing.

In the early 1980s, President Ronald Reagan was fighting the War on Drugs and authorities were cracking down.

Rodosvaldo Pozo, another Mariel refugee, was a victim of this federal surveillance. After he left his sponsor family in Sparta in the early 1980s, he eventually started a family of his own in La Crosse.

He also had a few run-ins with the law there — he was convicted of robberies, curfew and parole violations, as well as marijuana possession.

In the mid 1990s, Pozo ended up in prison for “being a party to the delivery of cocaine.” He said he took the fall for a loved one.

During his 22 years in prison, Pozo took time to better learn the U.S. and Wisconsin legal systems and even attempted to appeal his drug conviction.

“You know, sometimes people say I’m crazy. I’m not crazy. If you want results, if you want to move, you have to get it yourself,” he said.

He was unsuccessful in his appeal, but that didn’t stop Pozo from advocating for himself. He’s filed a number of other lawsuits regarding his treatment while in prison and in immigration detention. These cases have all been dismissed.

‘I went a little violent toward an inmate. You know, Jeffrey Dahmer’

Osvaldo Durruthy was in and out of prison — for drugs, extortion or battery — throughout the 1990s and early 2000s.

He was sentenced to Waupun Correctional Institution for 31 years for selling cocaine to undercover police when he was 34 years old.

“I can never say (I) regret (it) because…once I do something, I don’t look back. … I pay for my mistake,” Durruthy said.

Durruthy said when he was young, he felt “macho.” Going to prison didn’t make him want to change course. Not even getting shot back in 1982 made him rethink what he was doing.

What motivated Durruthy to eventually straighten out his life was his son, who was6 years old when Durruthy was sentto Waupun Correctional Institution.

“After my son visited me, and … his brothers and sister, everybody started visiting me — and that was when I became part of a family. I (saw) the scenario differently,” Durruthy said. “I’m not alone anymore. I got family. I got people who care for me. So I might as well forget about every little thing that I was doing wrong and make sure I get out here.”

He had to do something to get out of prison, so he could become a real family man outside the prison visitor’s room.

To get out, Durruthy decided he had to kill the most hated man behind bars.

“I went a little violent toward an inmate,” he said.

“You know, Jeffrey Dahmer.”

Durruthy said his plan was to get himself transferred to Columbia Correctional Institute in Portage. That’s where Dahmer was serving a life sentence after murdering 17 men and boys. Durruthy said he started taking pills and pretending like he needed psychiatric care, and that got him transferred.

“When I got to Portage, they put me in the same unit with Jeffrey,” Durruthy said. “Next door to Dahmer.”

Durruthy said at Columbia, the only place where all the units were together was at the chapel on Sundays. He attached a razor to a toothbrush, and went to church.

“I saw (Dahmer) and I was sitting … behind him. I (grabbed) him … on the wall, you know, after the priest was leaving,” Durruthy recalled. “I ended up attacking him. And the razor broke (on) his neck.”

The weapon fell apart. Dahmer only had a scratch. But Durruthy wasn’t done.

He got Dahmer in a chokehold and began beating him, he said. The guards separated them.

“I’m not proud of that. At that moment, you know, my mind was so disturbed,” Durruthy said.

(About four months after Durruthy’s attempt, Dahmer was killed by another inmate. Durruthy’s fight was dramatized in the 2022 Netflix show, “Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story.” The scene takes place in a chapel, but does not follow Durruthy’s story or newspaper reports from the time.)

You can hear the pain in Durruthy’s voice and see the sadness in his eyes when he talks about this situation. He thought this extreme act was the only way he could get out of prison in the U.S. — that as a Cuban exile, attacking Jeffrey Dahmer would force the U.S. to deport him back to Cuba.

“The reason I did it (was) because I wanted to go back to Cuba. … I tried to make it … political,” he said. “But I also want to go back to my country. I want to go back to Cuba.”

And if deportation didn’t work, he thought the killing could somehow help his family, even if he wasn’t with them in the U.S.

“If I kill (Dahmer), I might stay in prison. My family (could get) a lot of money. For some reason, I always thought if I kill him, Oprah is going to come to interview me. … The Black community, they’re going to love me, they’re going to send money, money, money, money, money.

“And my family, they’re going to live large in Cuba. My family in (the) United States, my family in Cuba, they’re going to live. … I don’t care about me because I already had 31 years, a sentence to die. … I never expect(ed) to get out,” Durruthy explained.

Durruthy was not sent back to Cuba. His family didn’t get any money out of it. He was sent to isolation for one year and had five years added to his sentence for battery.

Even so, it was a turning point in his life.

“I got people who care for me. So I might as well forget about every little thing that I was doing wrong and make sure I get out here.”

Osvald Durruthy

‘I think we are better men now’

While he was in prison, Durruthy took classes, like for parenting, to prepare him to take care of his grandkids once he got out.

“My kids were grown when I got out, but I saw my grandkids. I can take them to school. I can take them to a park and show them how to lead the right way in America. I’m able to do what needs to be done to raise them,” he said.

He took custodial service classes with hopes he’d get a job cleaning commercial buildings after being released.

He was released from prison in 2016.

“I had a bad past. Many Cubans like me had a bad past. (We all) did something wrong. But it was all childish,” Durruthy reflected. “Looking back, we (were never so focused on) being an American. Back in the days, you know, we were young. And we were wild.”

Durruthy knows he can’t change his past. So he focuses on the present and future.

“We try after all (these years) to become a little better (men), and … I think we are better men now,” he said.

He tries to make up for lost time with his son and his grandkids. He has friends he knows are good for him.

Just before the pandemic, Durruthy was working at a nursing home and loved it. He works out every day to stay healthy. There’s a bench press in his second bedroom.

When he’s not working out or spending time with family, he’s often volunteering with his church, making sure kids around Madison have food and clothes.

One certificate on his wall is one he used to cover up: a baptismal certificate.

“I’m so proud of myself because, you know … Jesus Christ and God is my number one in my life,” Durruthy said. “I celebrate differently from (other Christians). I just give thanks every time … and glorify. It’s what I do. I don’t read the Bible. I just go to God and (give) thanks. I go every morning, every night: ‘Thank you. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you. Forgive me for my sins and open the door for me and give me strength.’”

Durruthy said he appreciates life now more than any other moment in time.

“Maybe it’s because I’m in my 60s. I’m old but, you know, wise. I can say now that I would never go back to prison again,” he said.

Durruthy added that he’s waited a long time to share his life’s story: “This is like a dream come true for me, because, I’ve been I’ve been waiting for a long time to say something, to be heard, to be able to express myself — saying, you know, what I feel.”

After all he’s been through, Durruthy is in a good place today. But there’s one thing he wants to do, that he can’t: Go back to Cuba to see his family.

He’s not the only one.

Marcos Calderón had been working as a professional driver in Minnesota and Wisconsin. He also got caught with drugs and was arrested in 1988. That conviction sent him to prison in Minnesota, and it’s still impacting his life today.

Because he committed a federal crime, Calderón can’t vote, start a business, become a U.S. citizen or travel outside the country. That means as it stands now, he can’t go back to his home in Cuba.

“(We saw) how fast you can make money (selling drugs), and we were not aware of the consequences. We said we were thinking of the money, just like pretty much everybody, until you get caught. I’m still paying for that mistake,” Calderón said.

On the next episode of “Uprooted,” these Cuban exiles are in their 60s. They’ve made peace with their pasts. Now, they’re trying to visit Cuba one more time. But their pasts are standing in their way.

Editor’s note: WPR’s Alyssa Allemand contributed to this report.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.