Cuban refugees stuck in limbo in Wisconsin

By: Maureen McCollum, Omar Granados

Episodio 5: traducción al español próximamente

Editor’s note: This article contains brief mentions of violence and sexual assault.

Osvaldo Durruthy stepped foot in the United States for the first time in June 1980. He came to the U.S. from Cuba as part of the Mariel Boatlift.

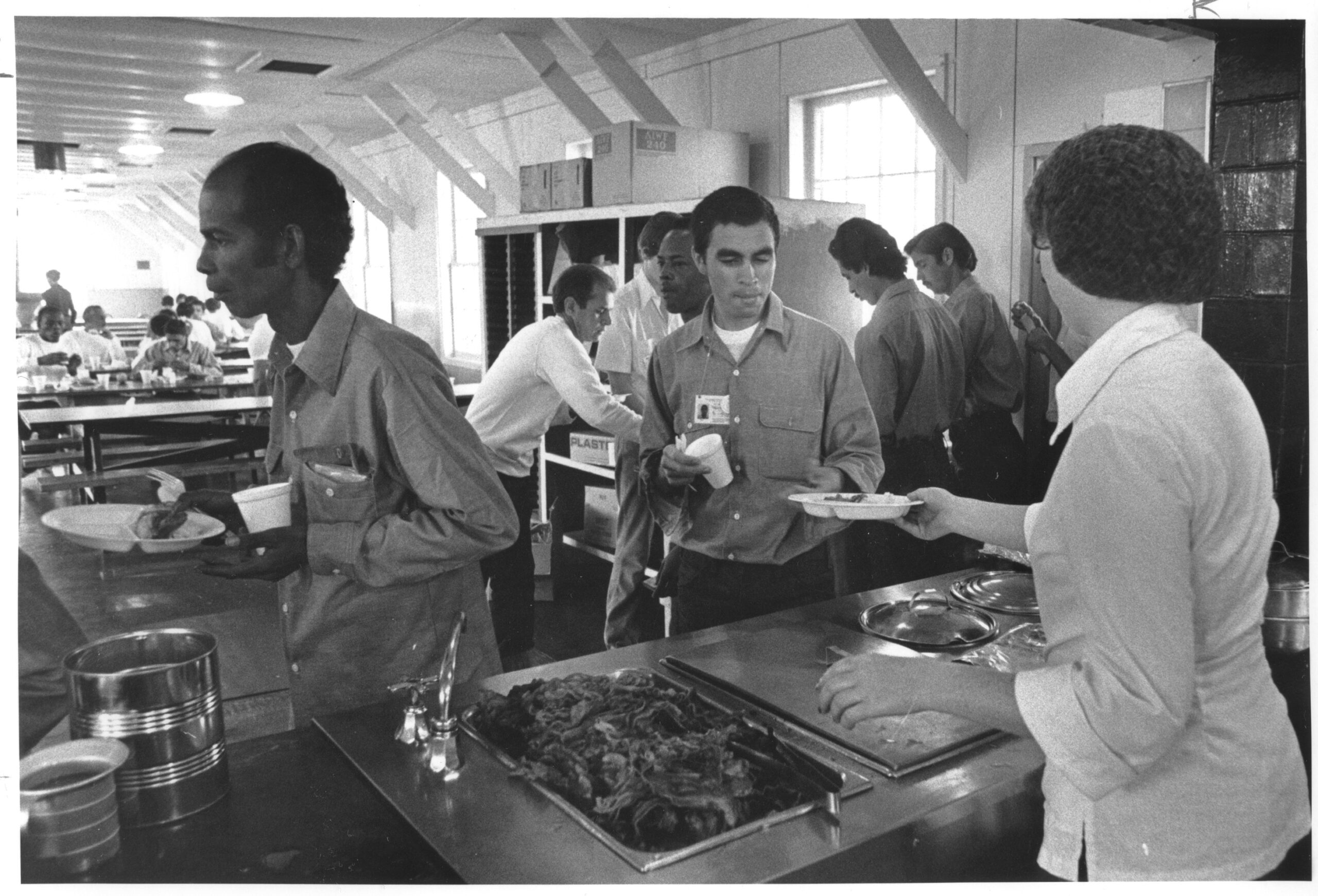

After arriving in Key West, Florida, he tried his first apple and had his first proper mess hall experience with an all-you-can-eat buffet. Soon after, he was whisked away to the Fort McCoy military base in Sparta, Wisconsin. Once he got there, he quickly realized he would be living in the soldiers’ barracks.

“I remember the first day that I put a foot in Wisconsin, Fort McCoy,” Durruthy said. “We’re getting out of the buses and everybody trying to run to get a room (in the) barrack (because) you got … four (private) rooms. The rest is open. So people try to run for a room.”

Once Durruthy staked out his bed, he spotted something outside.

“I see in the street something that looks like a refrigerator,” he recalled. “And I say to my guy, ‘Look! Let’s grab (the) refrigerator and put it in there, and we can have cold beer.’

“And I realized that night, (it was) too big for a refrigerator. And we got the surprise of a lifetime,” he laughed.

It was a porta potty.

For Cuban refugees like Durruthy, this was just the beginning of the refugees’ eye-opening experience in Wisconsin.

History of Fort McCoy

Fort McCoy was one of four U.S. military installations that housed Cuban refugees after the Mariel Boatlift. Almost 15,000 Cubans lived there in the summer and fall of 1980.

Fort McCoy was built in 1909 in Wisconsin’s Driftless Area. In addition to offering training to thousands of soldiers annually, some military mobilize at Fort McCoy before deployment.

During World War II, what was then known as Camp McCoy, became a Japanese, German and Italian internment camp. These were American civilians who were arrested and considered “potentially dangerous ‘enemy aliens,’” according to archives. Then in 1943, it transitioned to a prisoner of war camp, holding more than 10,000 German, Japanese and Korean POWs.

More recently, thousands of Afghan refugees were sent to Fort McCoy in 2021 after the country fell to the Taliban. It was the first resettlement effort there since the Cubans arrived in 1980.

On May 9, 1980, Fort McCoy staff received orders from Washington, D.C.to start preparing for the arrival of Cuban refugees.

They had to act fast to make Fort McCoy a designated resettlement center,equipped to house thousands of people.

Ryan Howell, the garrison archeologist at Fort McCoy, said the ability to ramp up suddenly is one of the reasons Fort McCoy was tapped as a resettlement center for the Mariel refugees.

“That goes back to World War II here. A lot of these facilities were basically being held vacant in case there was a war incident or something like that where you needed to ramp up,” he said. “The facilities here … this would have been one of the few bases that had the ability to bring that many people in.”

“I think we had about 150,000 soldiers trained in a year, (which) is not unusual. So we have housing for them. Fort McCoy was able to handle that load,” added Tonya Townsell, public affairs coordinator at Fort McCoy.

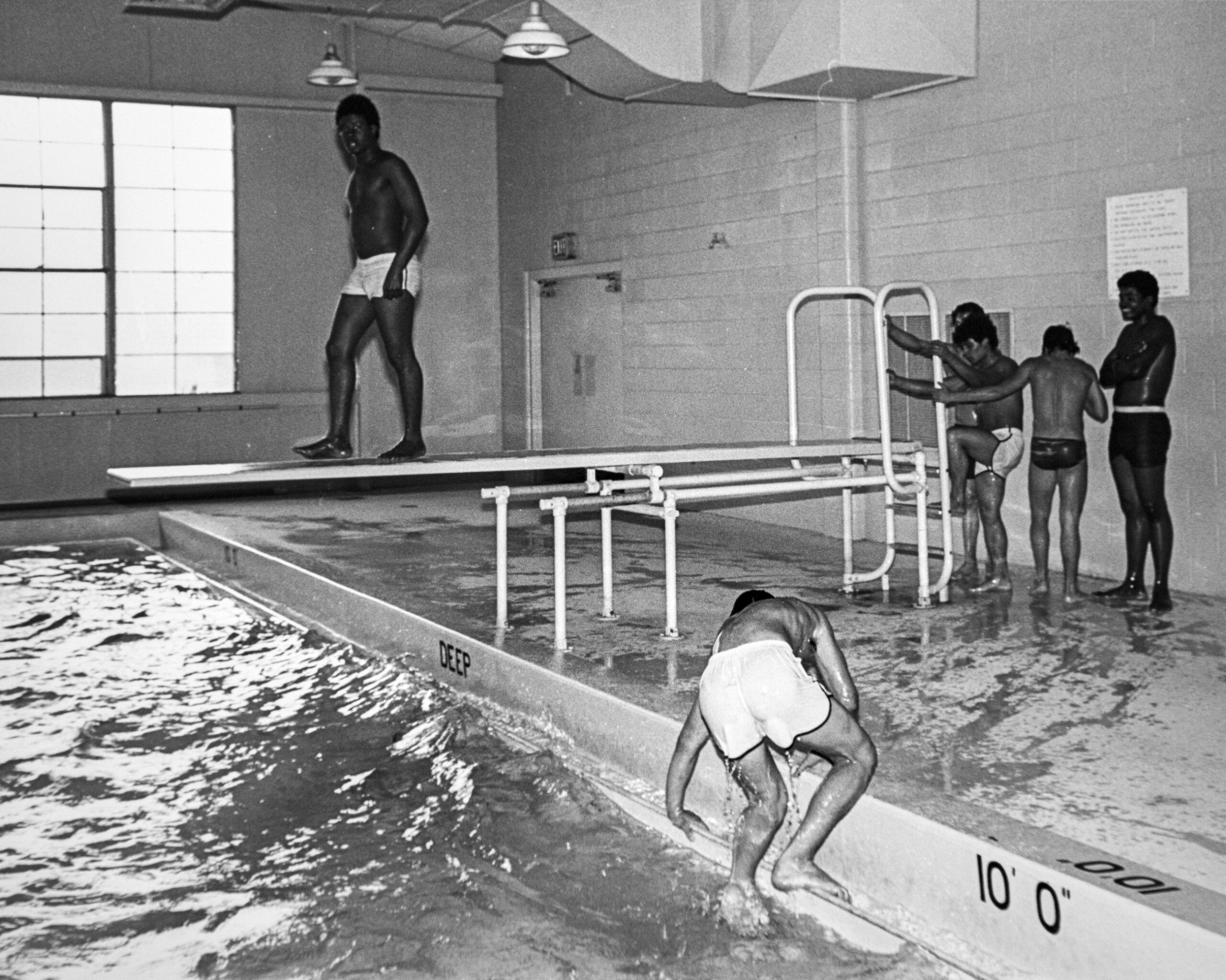

Townsell said the camp’s role during the Mariel Boatlift in 1980 was solely housing people and providing things like beds, laundry and athletic fields.

“It’s kind of like we’re your landlord, we’re the mall,” she said.

But Omar Granados, associate professor of Spanish and Latin American studies at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse and co-host of “Uprooted,” said placing the migrants in an isolated area could have been intentional.

“(Fort McCoy) is very isolated from everything,” Granados said. “I mean, Cubans are island people. We grow up surrounded by the sea. At Fort McCoy, you’re essentially landlocked…except for the occasional trout stream or pond.”

The book “Boats, Borders, and Bases: Race, the Cold War, and the Rise of Migration Detention in the United States” by UW-Madison’s Jenna Loyd and Wilfrid Laurier University’s Alison Mountz explains how isolation was used to deter people from immigrating to the U.S.

They argue, according to Granados, that the creation of the Mariel exodus processing and resettlement centers was a foundational step toward the militarization of immigration detention in the U.S. Placing refugees in remote and hostile locations was a way to deter more Cuban exiles from making the journey to the U.S.

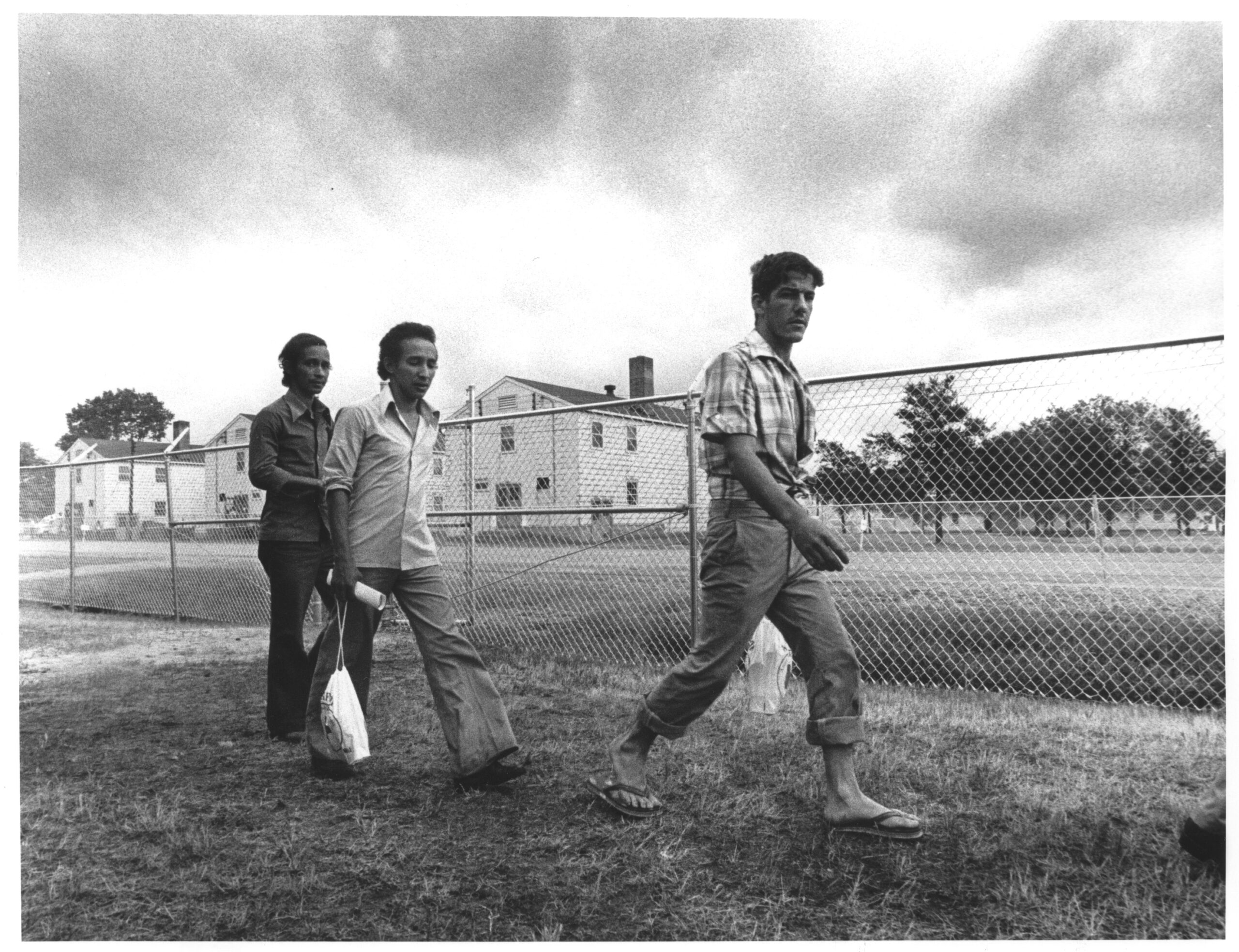

“Fort McCoy is a perfect example of how living in the middle of a secluded, guarded military base with barbed wire fence around you and being looked over by military police for months would send that message to future migrants from the Caribbean and Central America to not engage in migrating into the United States,” Granados said.

Welcome to Fort McCoy

When Ernesto Rodriguez, who now lives in La Crosse, arrived in Key West, Florida, in June 1980 as part of the Mariel Boatlift, he boarded a plane later that day. He was sent to Miami, Florida, where he stayed for one night.

“In the morning, there was the big plane,” Ernesto said. “They say, ‘You see the plane over there? Get in it.’

“There was a big line and we get in the plane. And … I don’t know where we go after,” he continued.

He had no clue he was on his way to Fort McCoy in Wisconsin — or that Wisconsin was even a place.

Once the refugees arrived at Fort McCoy, they essentially started their lives in the U.S. as detainees, Granados said. They spent time with federal officials in interrogations and interviews.

These refugees didn’t travel with their criminal or medical records, and the way crimes were defined by Cuba and the U.S. was different, so it took a long time to figure out who was who and what they did wrong — if anything — back in Cuba, Granados added.

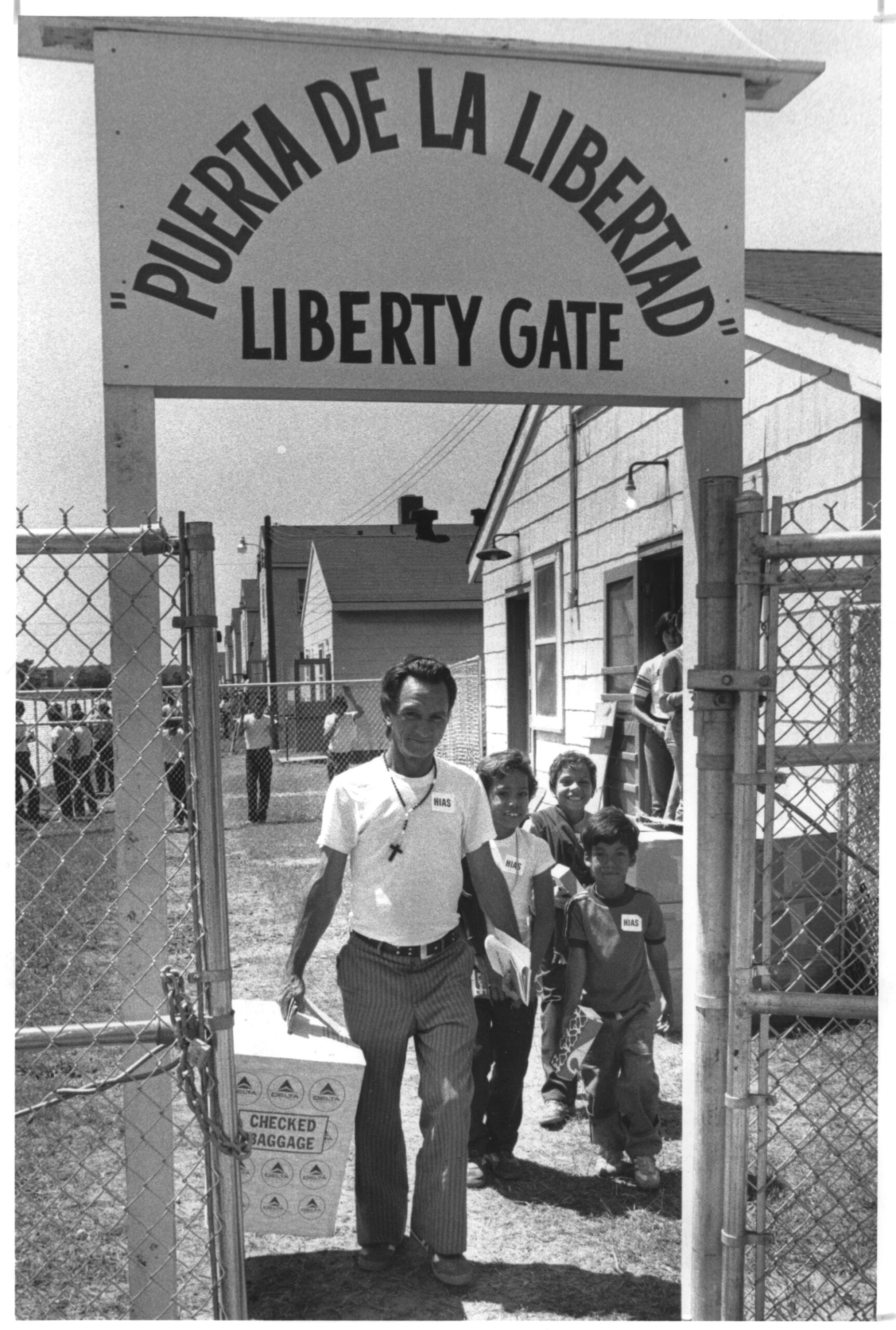

The Mariel refugees were classified under a new immigration designation: the Cuban Haitian Entrant Program. They could not get out of Fort McCoy without a family member or sponsor vouching for them.

As the refugees waited for sponsors or family, they needed food, health care and places to sleep at Fort McCoy.

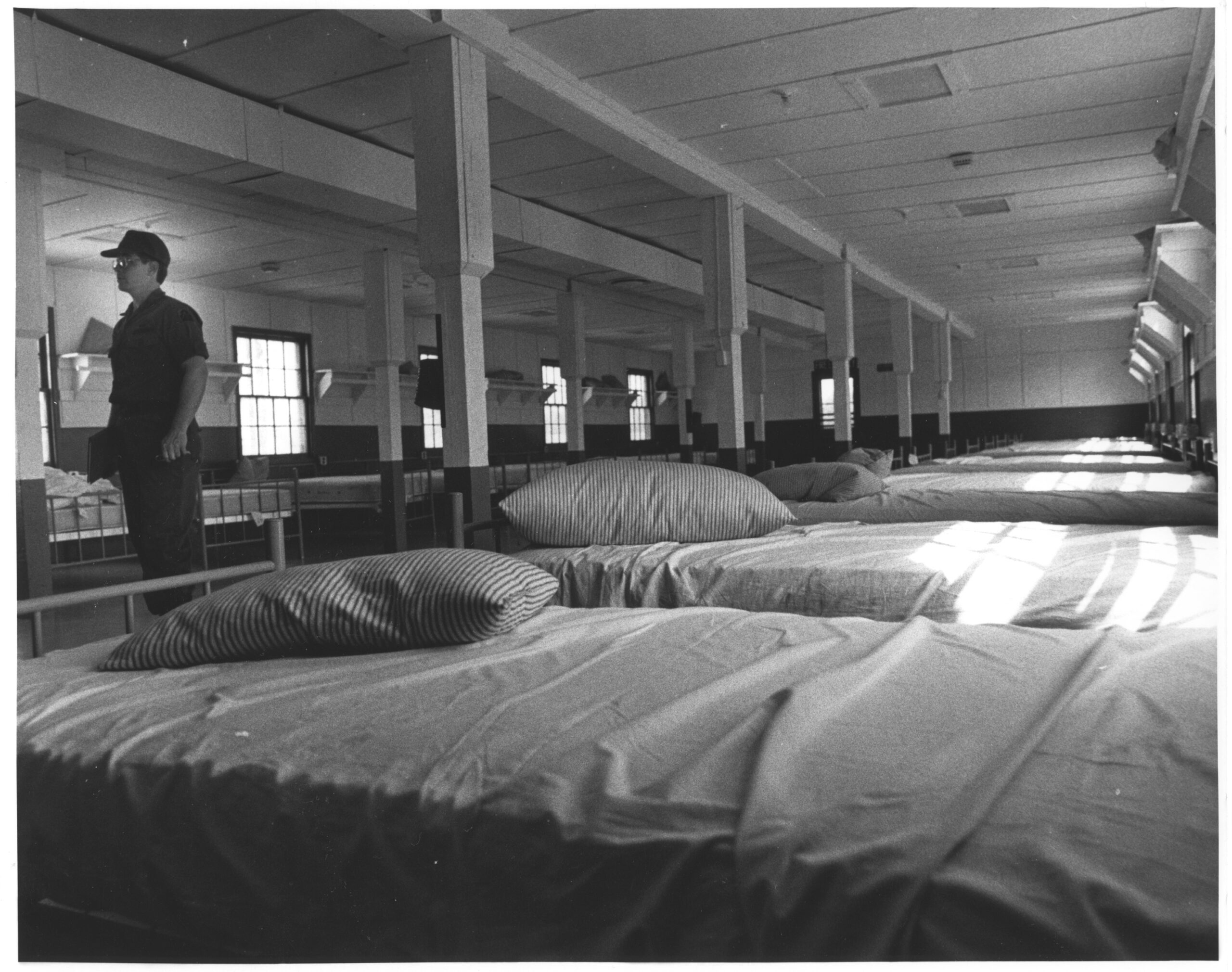

The barracks were organized by blocks and kept people in specific areas. It was mostly men at Fort McCoy, but families, juveniles and those who were considered dangerous criminals were all kept separate from the general population.

The walls in the barracks’ sleeping areas were lined with twin-sized beds with metal frames. Howell, the Garrison archeologist at Fort McCoy, said there was no air conditioning, no window screens and no proper insulation.

“These things would have been interesting to live in(in) the middle of Wisconsin summer and then in the middle of Wisconsin fall,” Howell noted.

To meet the basic needs of the Cuban refugees, the federal government hired more than 1,000 people to work as kitchen staff, teachers and medical personnel.

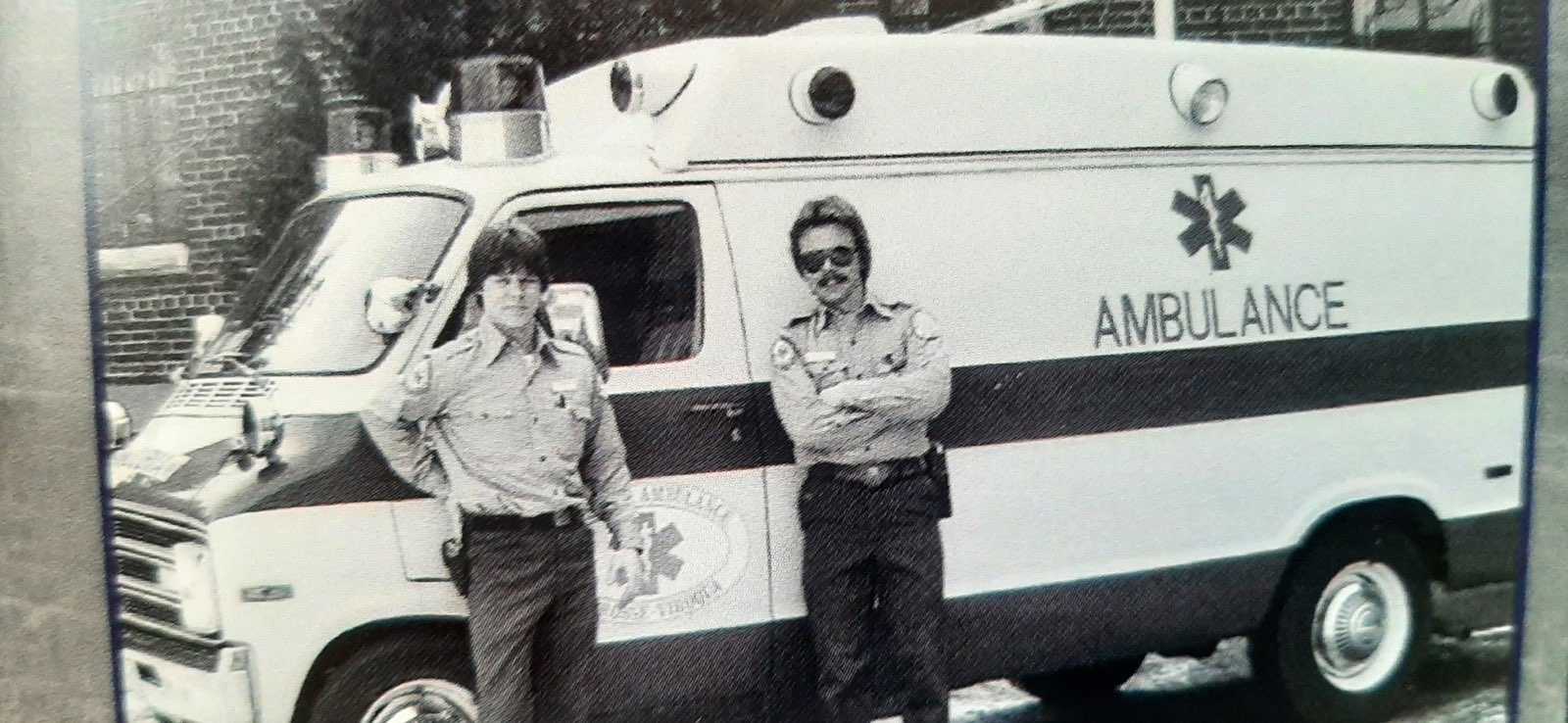

One of them was Rich Rice of La Crosse. In the summer of 1980, Rice was 25 years old, working as a basic EMT for Tri-State Ambulance in La Crosse. The company had received a federal contract to be emergency responders focused on the refugees as they arrived at Fort McCoy. The job started right on the tarmac.

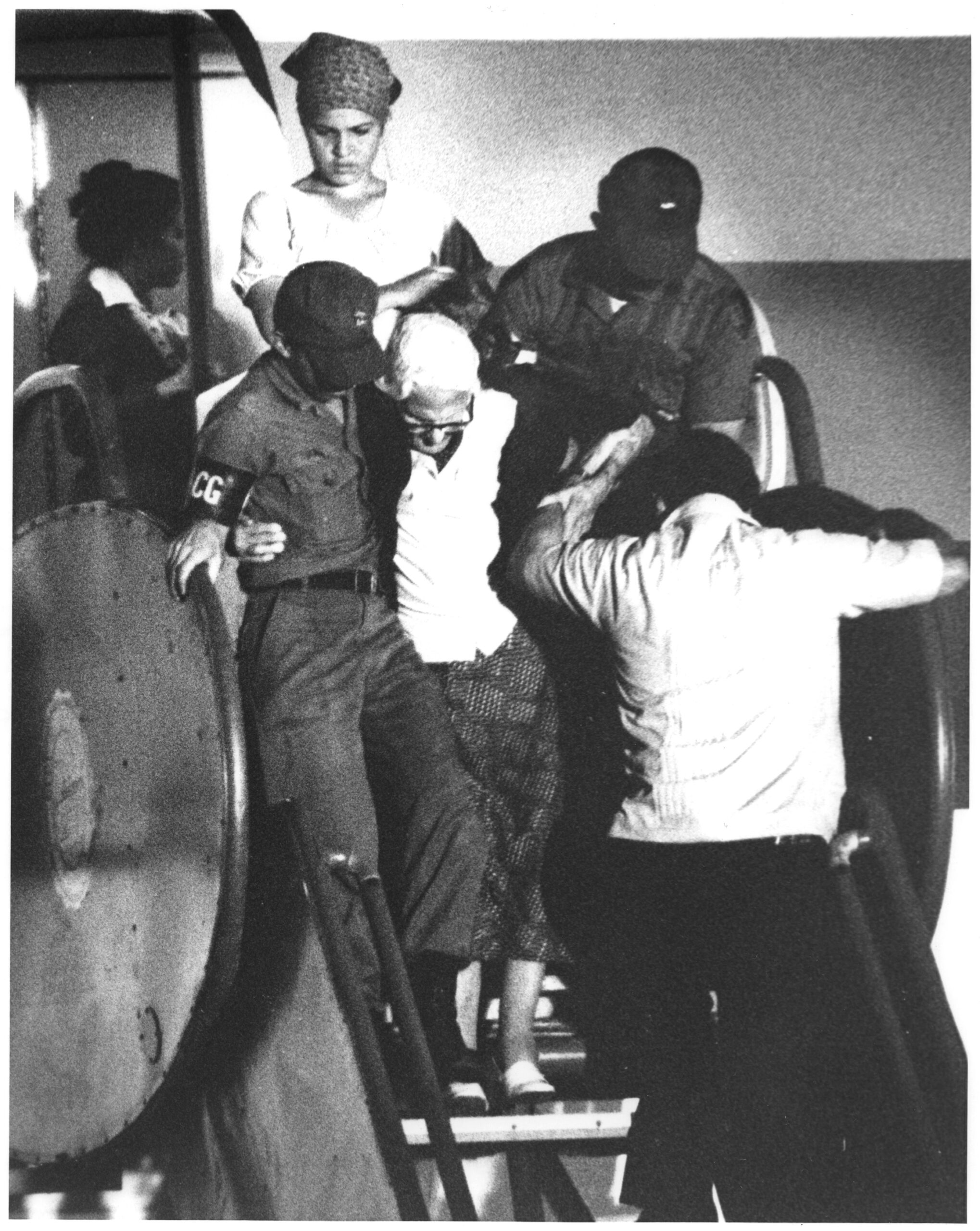

“We simply rolled out to the La Crosse airport with a single ambulance and two EMTs on board. And all of a sudden, you know, we’re presented with a planeload of refugees,” Rice recalled. “And then we were doing medical triage as these folks came off the airplane and they were in all kinds of medical conditions. Some were healthy and happy and walked to a bus, and others needed to literally be carried from the airport.”

He said local doctors, nurses and paramedics had to make quick decisions about whether to bandage someone up on the spot or send them to a nearby hospital. Plus, there was a language barrier. Rice had to learn new phrases quickly, like, “¿Donde le dueled?” or, “Where does it hurt?”

Rice said first responders didn’t have things like pop-up tents or two-way radios, so they had to improvise. But every day became more organized than the last on the tarmac and at Fort McCoy, according to Rice. Infrastructure improved, with Fort McCoy adding various clinics and bringing in physicians.

“It really became a pretty full-blown medical operation,” Rice said. “We had to watch that building a little village, basically, from scratch.”

Sports and English lessons

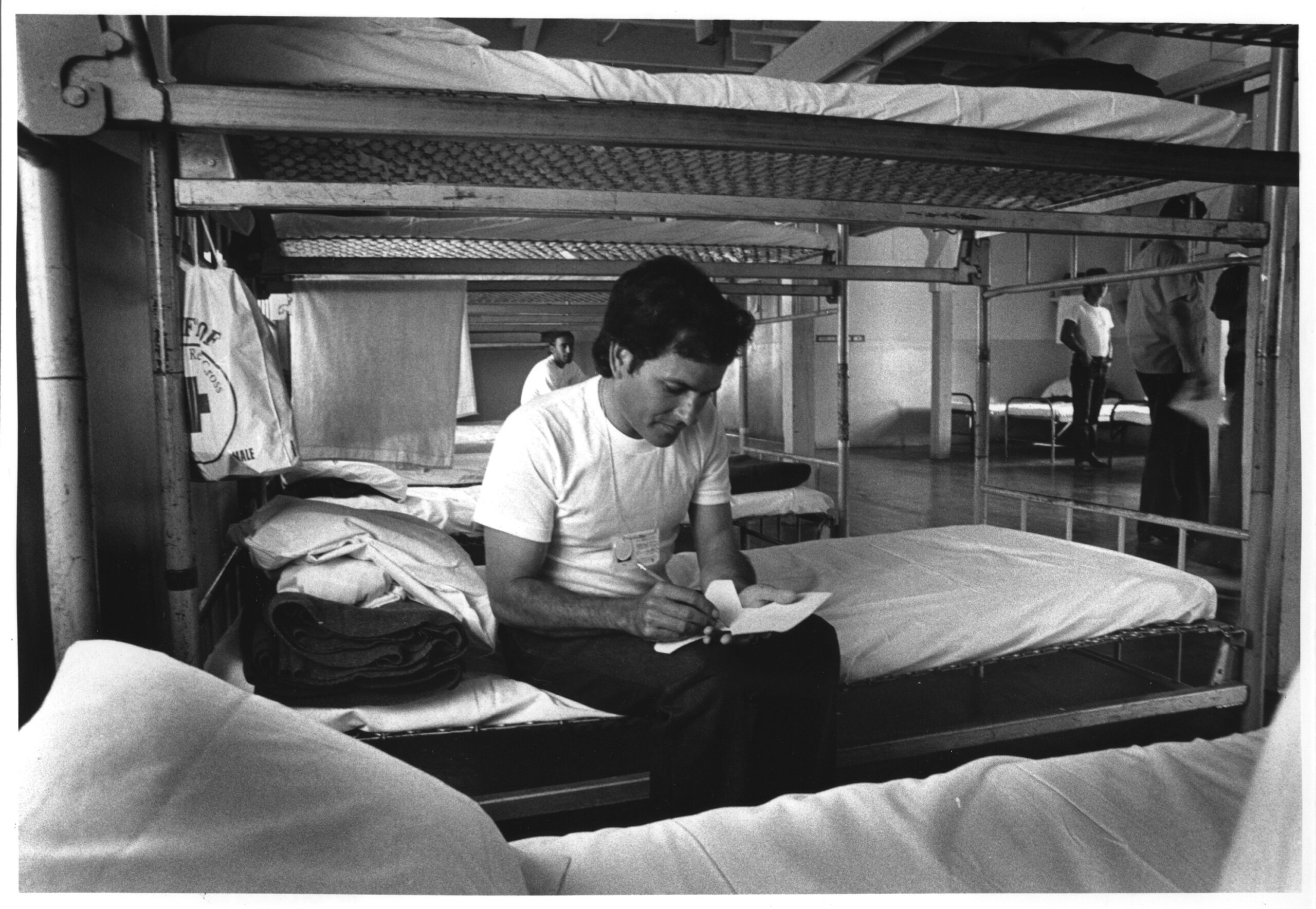

While Fort McCoy staff was providing medical care, handling refugees’ records and assigning people to barracks, the Mariel refugees were passing the time, wondering what would happen to them.

Some people spent their days playing cards or chess. People also played sports like soccer, volleyball and baseball.

Rodosvaldo Pozo, who now lives in La Crosse, said he played baseball and walked the perimeter of their assigned area.

“I used to run a lot,” Pozo said. “I used to run for hours, then walk.”

Ernesto said he spent a lot of time playing “Cuban cards” and socializing with other refugees.

“I would talk with people in the park,” Ernesto said, smiling. “When I say park, it was like a tree, essentially.”

Granados said they were trying their best to continue a way of life that was similar to what they had in Cuba. There were even some monumental life moments that took place at Fort McCoy. A couple got married. Babies were born to refugees at the camp — in fact, the first one was born on the Fourth of July.

Participating in these daily activities was a way to stay connected to home, but experiencing these moments in a secluded and restrained manner wasn’t the same as life back in Cuba, Granados added.

To leave Fort McCoy, refugees needed help filling out paperwork to find family members or sponsors across the U.S., and to do that they needed translators.

Rosa Hamilton was a Spanish teacher at Sparta High School. She was hired at Fort McCoy in 1980, and ended up bringing her students to work as translators.

“They just hired whoever could speak Spanish or whoever told them that they knew some Spanish,” Hamilton said. “We have people from all over coming into Fort McCoy and wanting the interpreting.”

But the lack of professional translation left a lot of room for errors, Hamilton added.

While working with the refugees, Hamilton saw another need. Soon, federal officials allowed her to open a classroom for children.

“I had my little bell early in the morning with a lot of candy, and the kids (would) follow me. So we started in one of the barracks. I started teaching the children while the parents were trying to get all the information to resettle with their relatives because it was a lot of paperwork. They did not get out as soon as I thought that they would,” she said.

Hamilton’s classes started to grow. When the parents saw how much their children were learning and how much fun they were having, they wanted to learn, too. She also took teenage students on field trips off the base.

Kitchens, mess halls and hunting

Refugees formed strong bonds with staff members, like Hamilton. These relationships between Cuban exiles and local staff at Fort McCoy were pretty common, said Granados. People who worked in the kitchens at Fort McCoy were no exception.

Ernesto would hang out in the kitchen and show American staff how to make Cuban food, like congri with black beans, rice and chicken. This was significant since the Cubans hadn’t developed a taste for the head cook’s American food yet.

“One day, he say, ‘Do you guys like macaroni and cheese?’” Ernesto recalled. “What the hell is the macaroni and cheese? I know macaroni, but you want a cheese in the macaroni?”

Some refugees turned to nature to hunt their food. Fort McCoy is a popular place to go hunting in southwest Wisconsin, and that remained the case when the refugees lived there in 1980.

John Satory of La Crosse worked in the Army’s dental clinic at the time. He said some Mariel refugees wrestled deer by hand and then cooked it rotisserie-style.

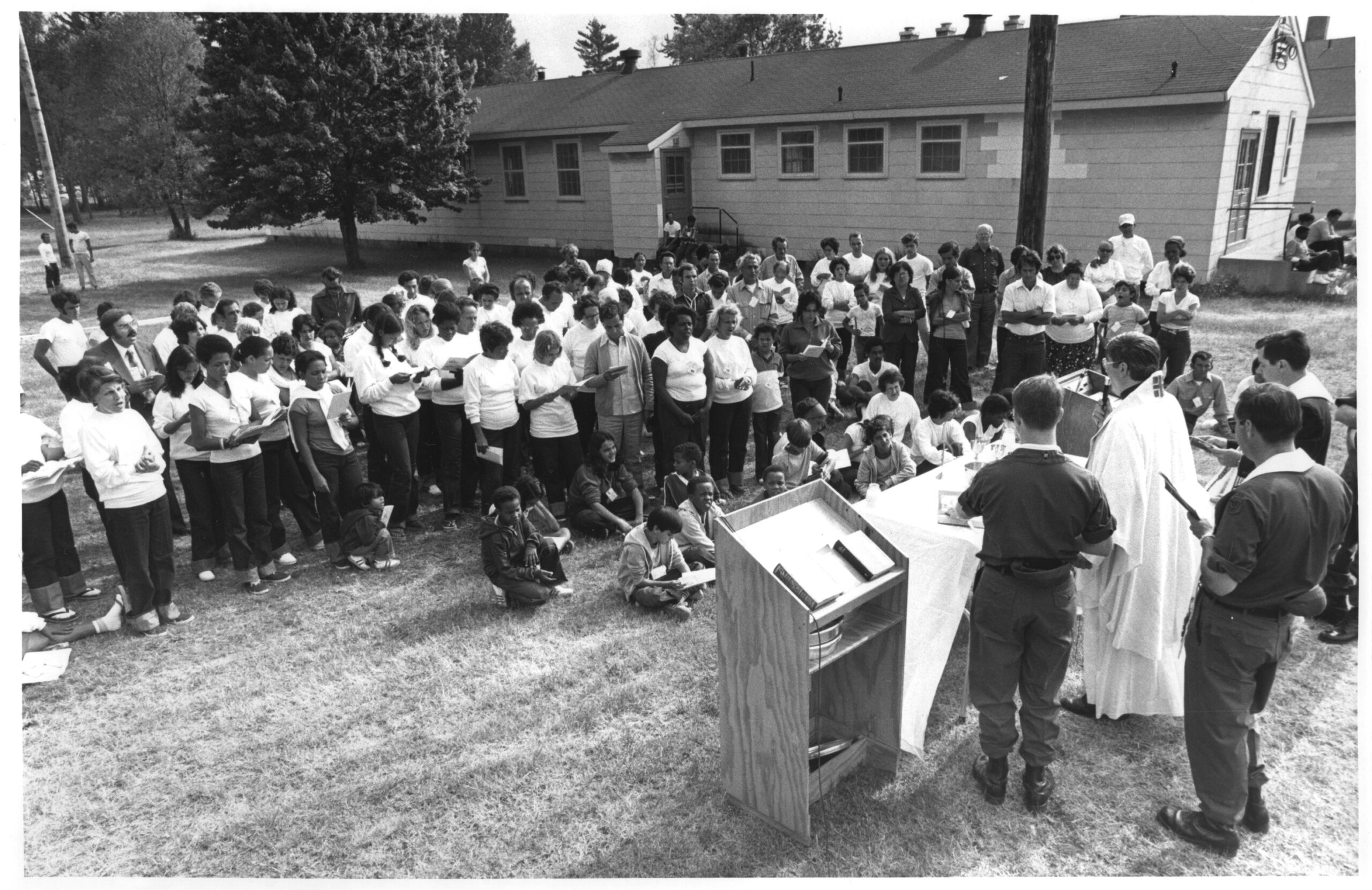

Practicing religion

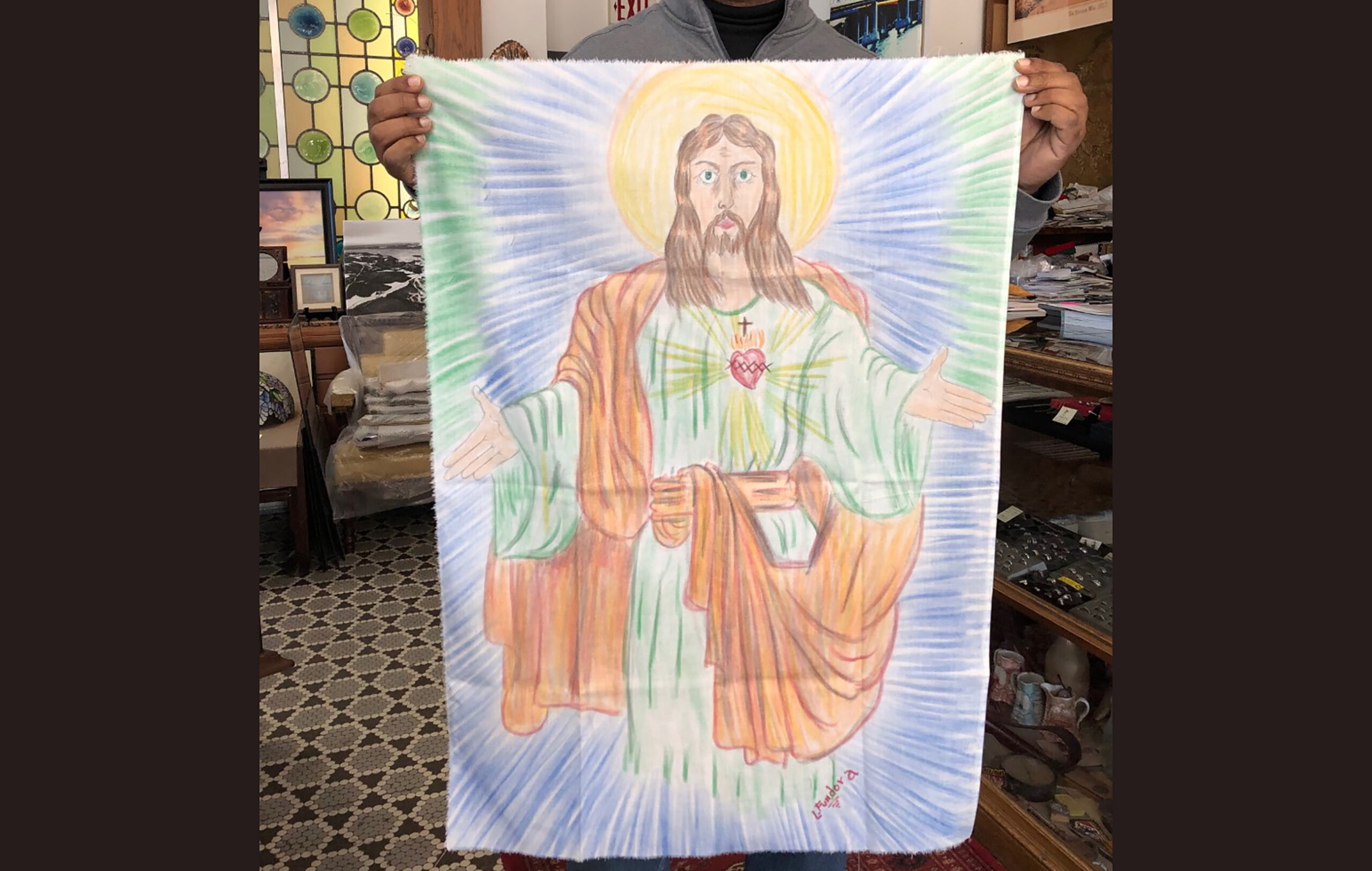

Food wasn’t the only aspect of Cuban life taking root at Fort McCoy. The refugees were now able to openly practice religion.

After the Cuban revolution, religious practice was restricted in Cuba, although many residents still practiced Catholicism and Santería privately in their own homes.

As the Cuban exiles ended up at Fort McCoy, local religious organizations stepped up to help the refugees with donations and assistance. The United States Catholic Conference of Bishops, formerly the United States Catholic Conference, and other religious organizations handled most of the sponsorship placements.

Local churches organized religious services at Fort McCoy, like Catholic masses, which began just three days after the first people arrived.

Some refugees would set up and give religious offerings, such as apples, to La Virgen de la Caridad de Cobre, who is the patron saint of Cuba, Granados said. She is the virgin that every rafter or every migrant worships in exchange for the success of survival in the sea. To Mariel refugees, La Virgen de la Caridad de Cobre is a symbol of their journey, he said.

Salsa music and WRPC

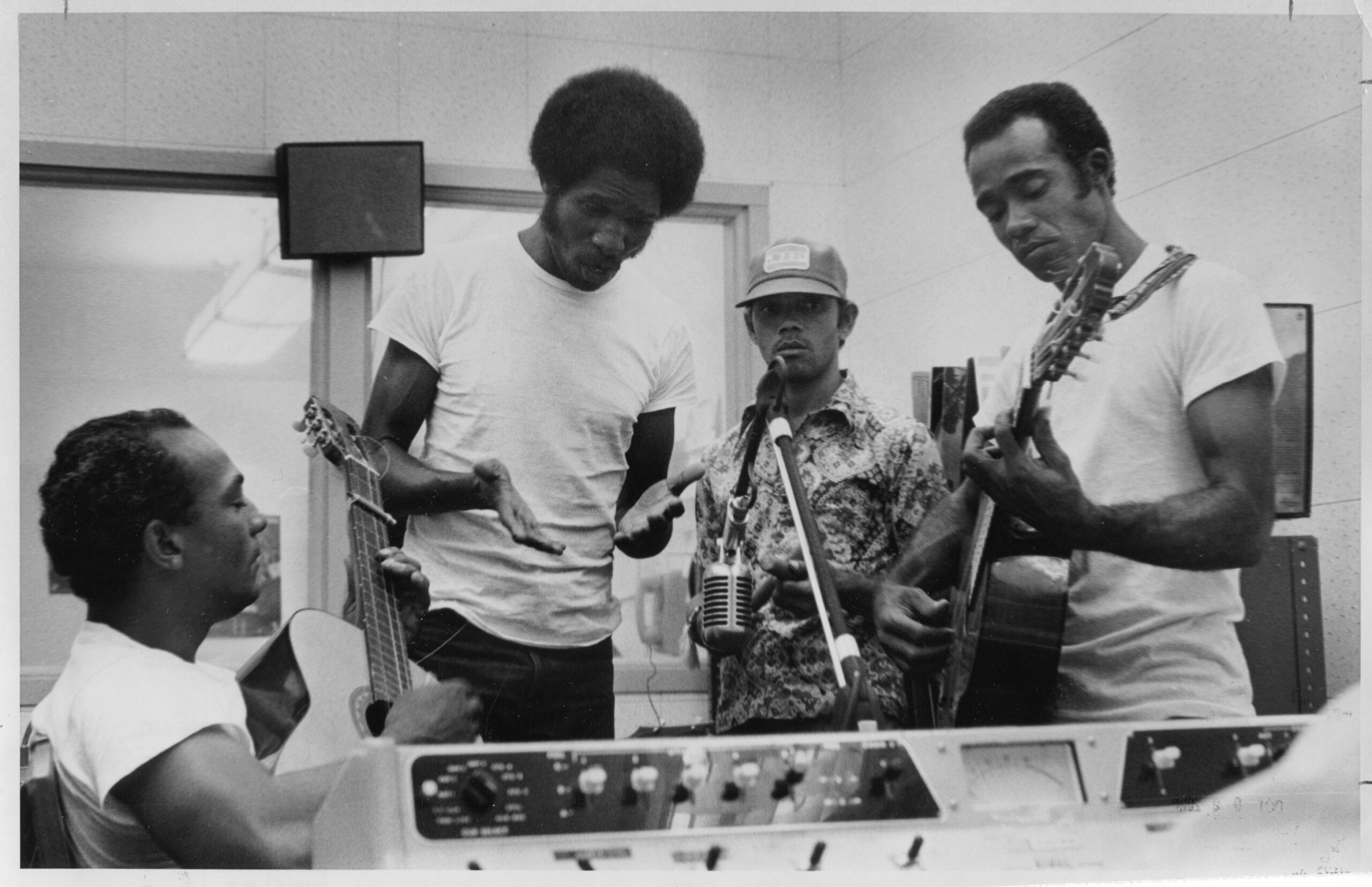

In between going to mass, taking classes and playing baseball, there was also music.

Dancing and listening to music was exactly what Osvaldo Durruthy, who now lives in Madison, wanted to do to pass the time at Fort McCoy.

“I’m good at dancing. Dancing was my life,” he said.

He heard a band was forming. So he auditioned as a dancer, taught himself bongos and earned a spot with the band.

“We all got together, started playing music. And that was when I ended up going to different places,” Durruthy said. “That was my way out of the environment (at) Fort McCoy. I just want(ed) to get away.”

The band played for people at Fort McCoy and even toured around the Midwest while they were still living in the barracks.

There was hope that efforts like this tour could help the Cubans find sponsors. These folks were basically ambassadors of Cuban culture in Wisconsin, Granados said.

“They’re trying to improve the image of Cuban people and the stereotype of the criminals at Fort McCoy. It was not only music, but they would also go to high schools to play baseball with high school students. And it was good press for the refugees,” he added.

Not only did Fort McCoy have house bands with people like Durruthy, but musicians came to the base to entertain the refugees, like Eddie Palmieri. Palmieri is a renowned pianist famous for playing salsa and Latin jazz.

“We all got together, started playing music. And that was when I ended up going to different places.”

Osvaldo Durruthy

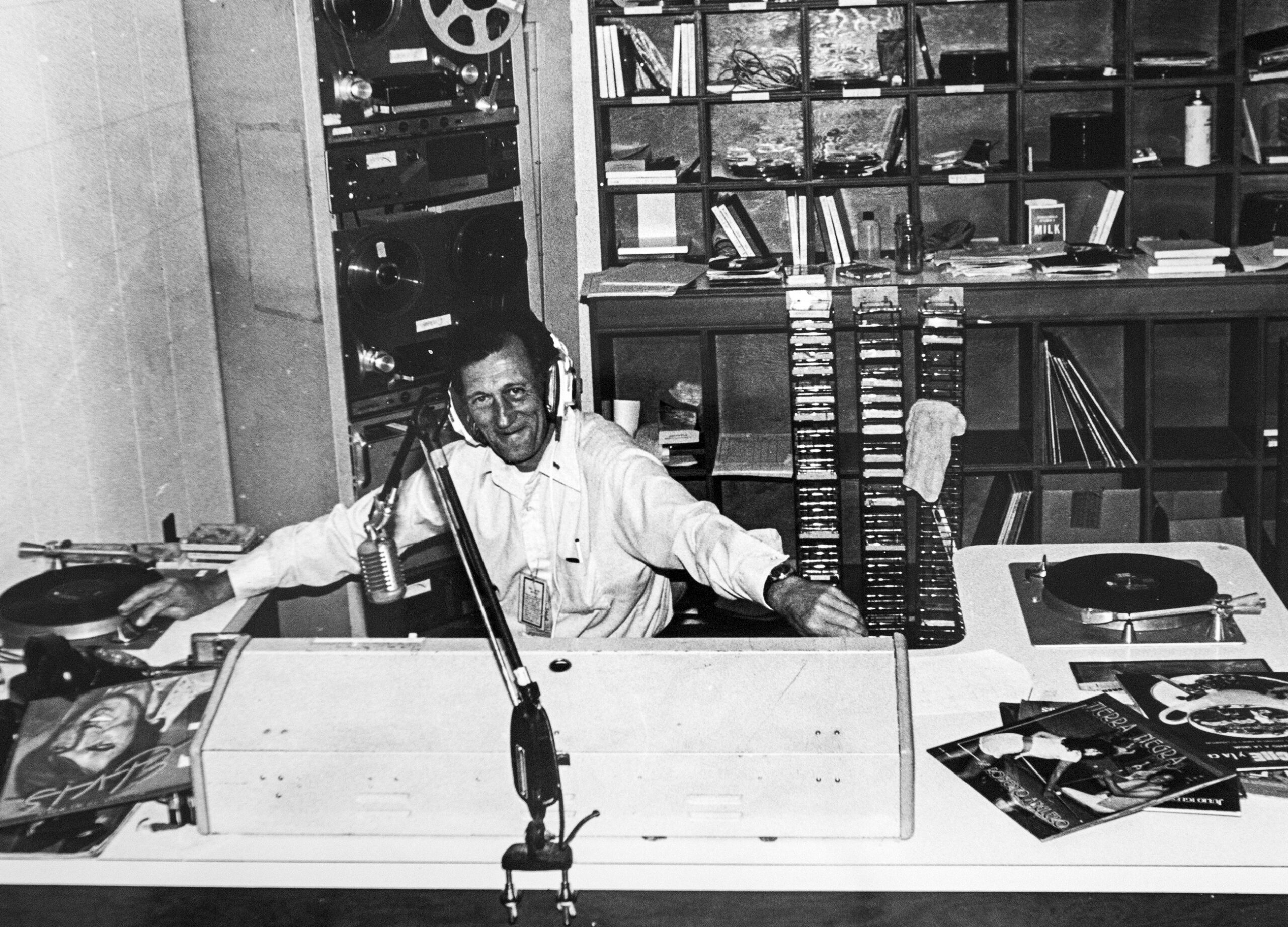

Cuban music was also broadcast throughout Fort McCoy on a radio station set up on the base. DJs at WRPC spun records as a way to help the refugees feel connected to home. It billed itself as “The Voice of Liberty.” The station was run by the 13th U.S. Army Psychological Operations Battalion, or PSYOPS. It was even profiled on NPR’s “All Things Considered” in September 1980.

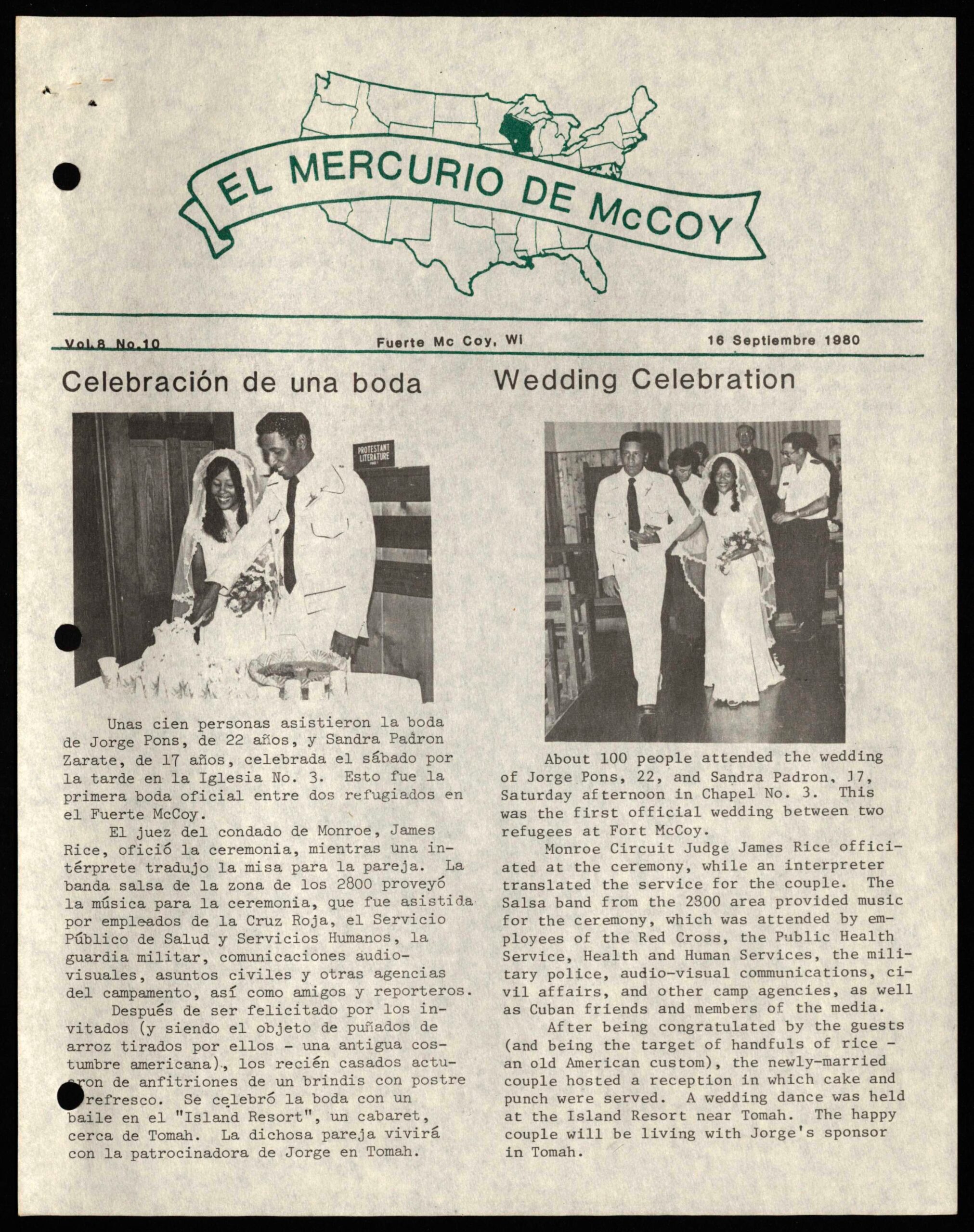

El Mercurio de McCoy

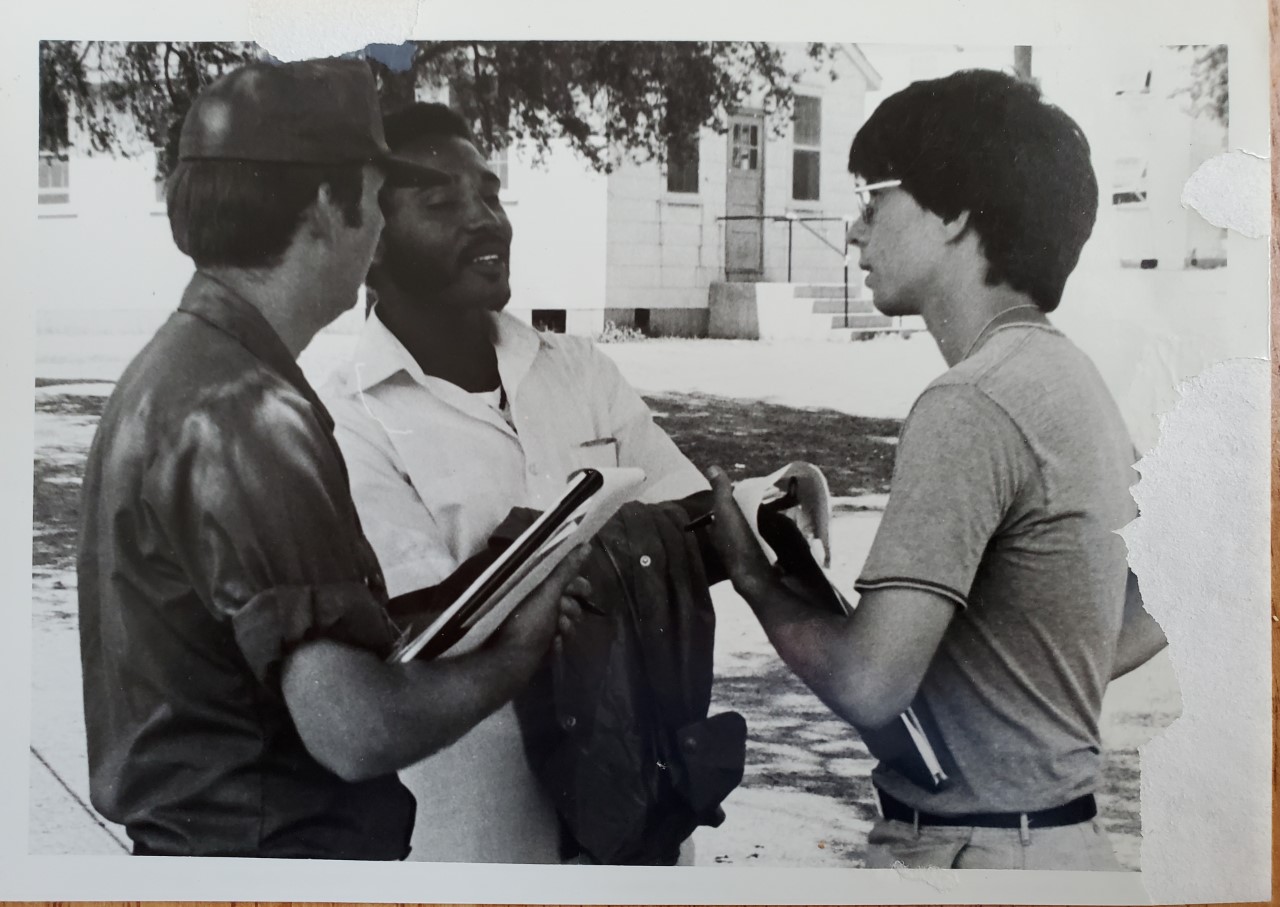

In the summer of 1980, two lifelong friends from La Crosse, Wisconsin, Will Ferguson and Adolf Gundersen, needed jobs. It was either babysit or take on an exciting opportunity working with Cuban refugees at Fort McCoy. The UW-Madison Spanish majors had just wrapped up a semester abroad in Spain, so they were excited to keep using their language skills — and chose Fort McCoy.

As they waited to be interviewed for jobs at the camp, Gundersen said he wondered how he was going to be vetted, to make sure he could actually do the work.

“Turns out they didn’t. They just had no one qualified to vet us. They had nobody capable of speaking good enough Spanish to submit us to any kind of examination. So I don’t recall being asked other than in English, ‘Do you speak Spanish?’ And then you said, ‘Yes,’” Gundersen said. “Then you swore an oath to the Constitution, which we readily did. And then we were off to be sorted into the different kinds of work that we did. We were sort of herded into a big room.”

Ferguson and Gundersen were hired as interpreters and media liaisons, connecting local and national reporters with Fort McCoy staff and refugees.

They also worked on El Mercurio de McCoy, an internal newspaper overseen by PSYOPS.

Ferguson explained what they were trying to do with the paper: “We were trying to answer some of the questions that the Cubans had — simply, ‘What’s going on here? What’s happening in the world?’ As well as, ‘What’s happening in the camp?’” Ferguson said. “It seemed really important to try to get that right, telling them what are the most important stories nationwide, worldwide, and then what’s happening here.”

Gundersen said he remembers cutting up press clippings for El Mercurio.

“But there was also the non-press related content of El Mercurio, which I would say was sort of like civics education and other kinds of things … This is what life in America is going to be like,” Gundersen said. “So there was day-to-day news and then there was also cultural education.”

El Mercurio also included sports scores, resettlement updates and English lessons.

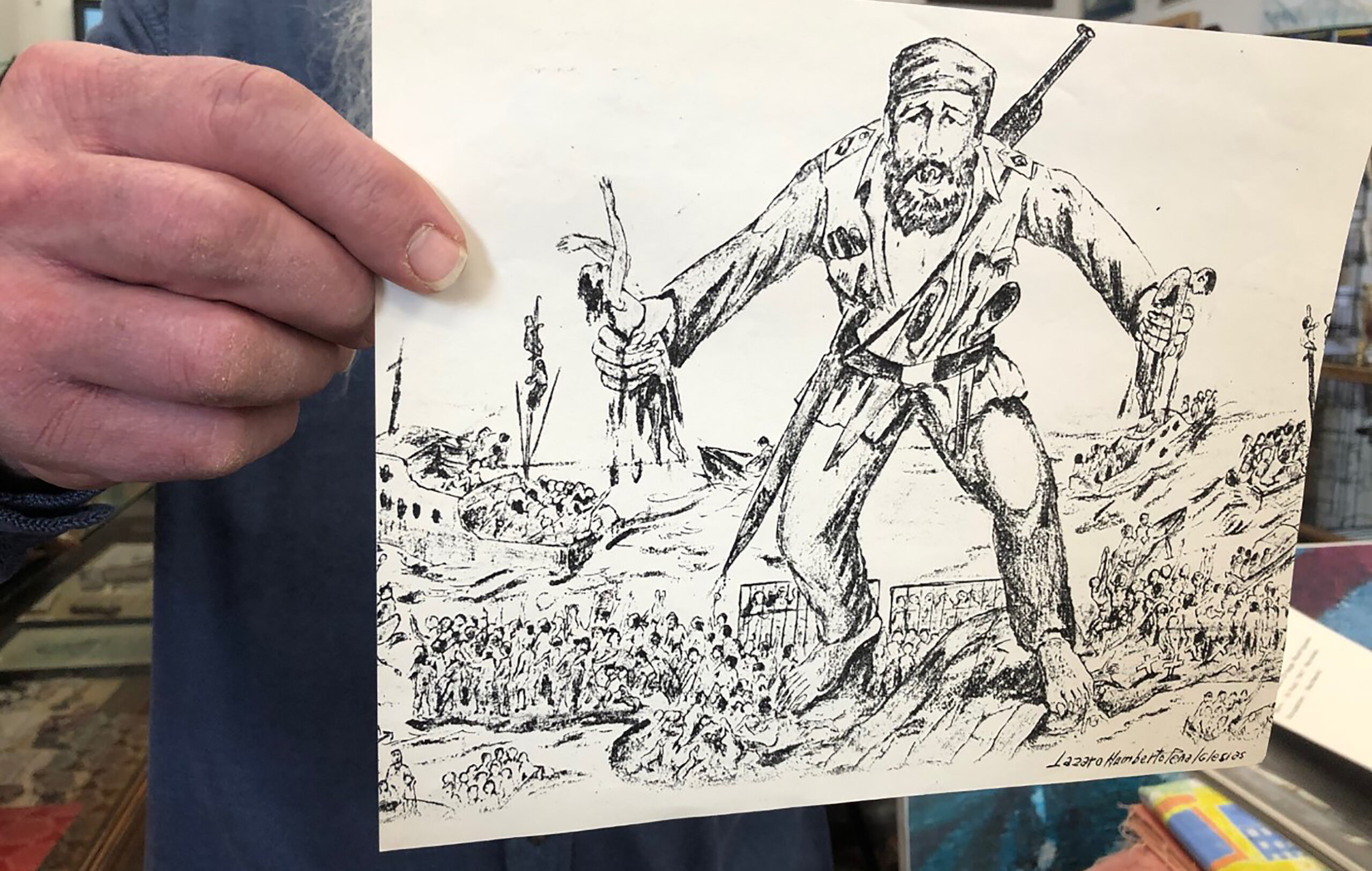

The paper featured several profiles on the Cuban refugees themselves. These were a way to get refugees sponsored, according to Granados. Readers would see stories about the refugees’ talents and their pasts in Cuba. Any kind of criminal history was framed through the injustice of living under Fidel Castro’s government at the time, Granados said. These stories from El Mercurio were in juxtaposition to those from the outside press, which focused heavily on the negative, usually criminal aspects of the refugees.

The articles also showed the meaningful connections being built among the refugees, military staff and volunteers at Fort McCoy — close, interracial relationships that were not as strong in society outside the camp, said Granados.

Every El Mercurio article was written in English and Spanish. And while the newspaper tried to represent the refugees in a kinder, more accurate way, it fell into stereotypes.

Granados shares one example of the newspaper, asking refugees to practice English vocabulary centered on hard labor.

“We see a lot of activities where refugees are supposed to practice the names of tools, you know, how to say hammer, how to say drill. But we don’t see anything about how to say university,” he said.

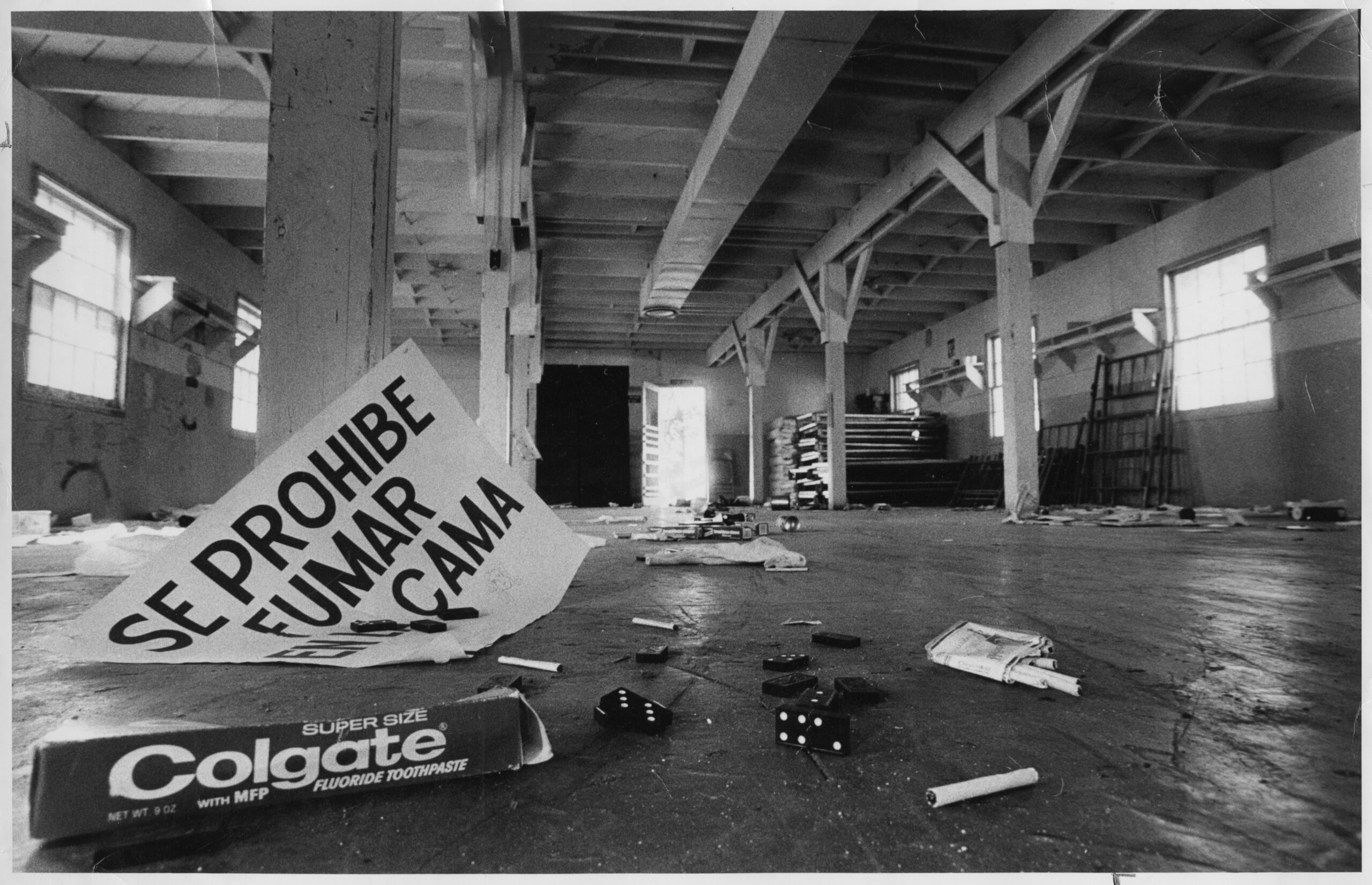

El Mercurio also reminded people to stay out of trouble and pick up their trash. There were cartoons drawn by refugees discouraging people from jumping the fence — something that happened as people desperately wanted to get out of Fort McCoy.

Purses, paint and protest

John Satory owns Satori Arts Gallery in downtown La Crosse. Satory also worked at Fort McCoy in 1980 in the Army Medical Corps’s dental clinic.

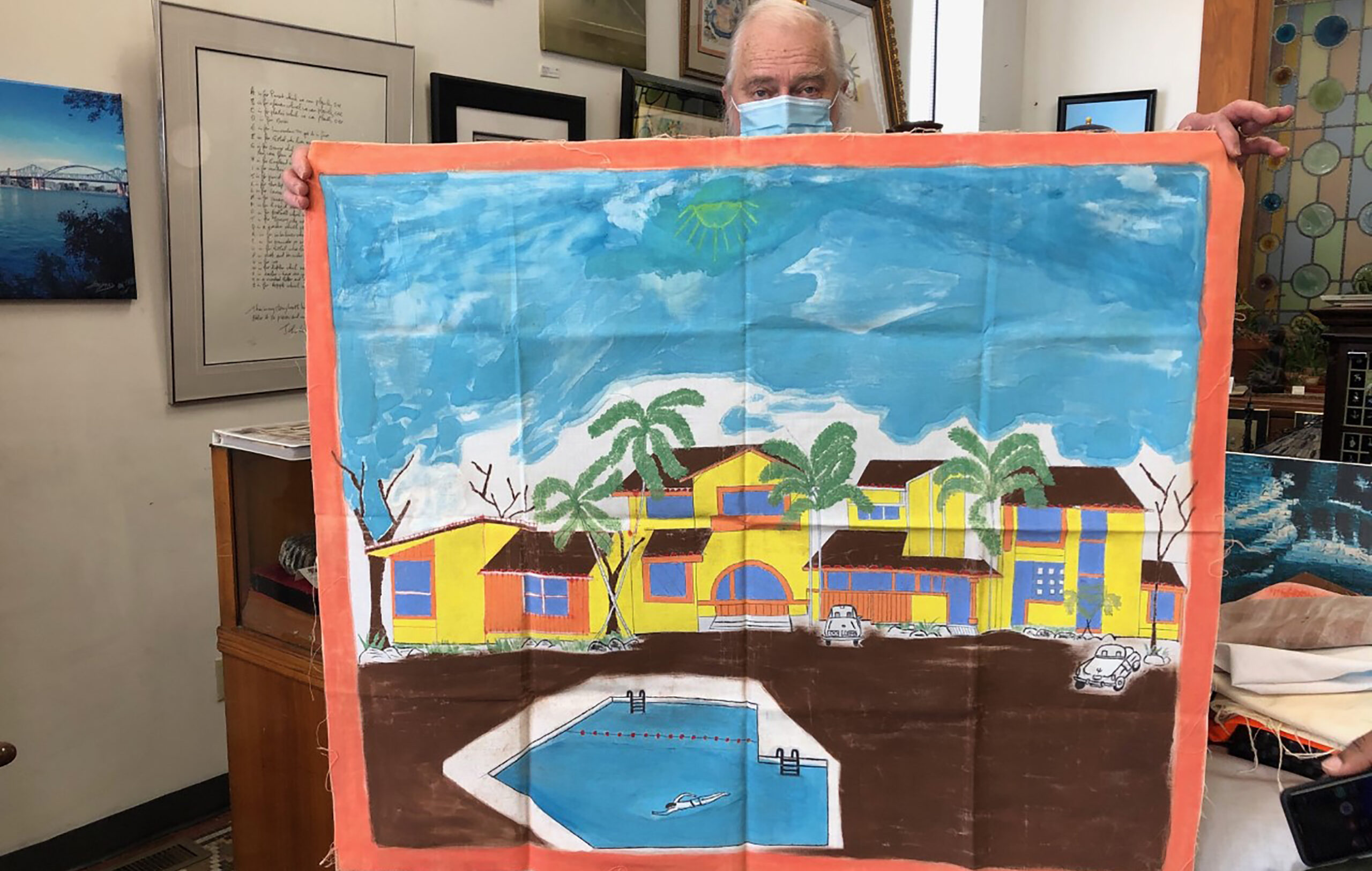

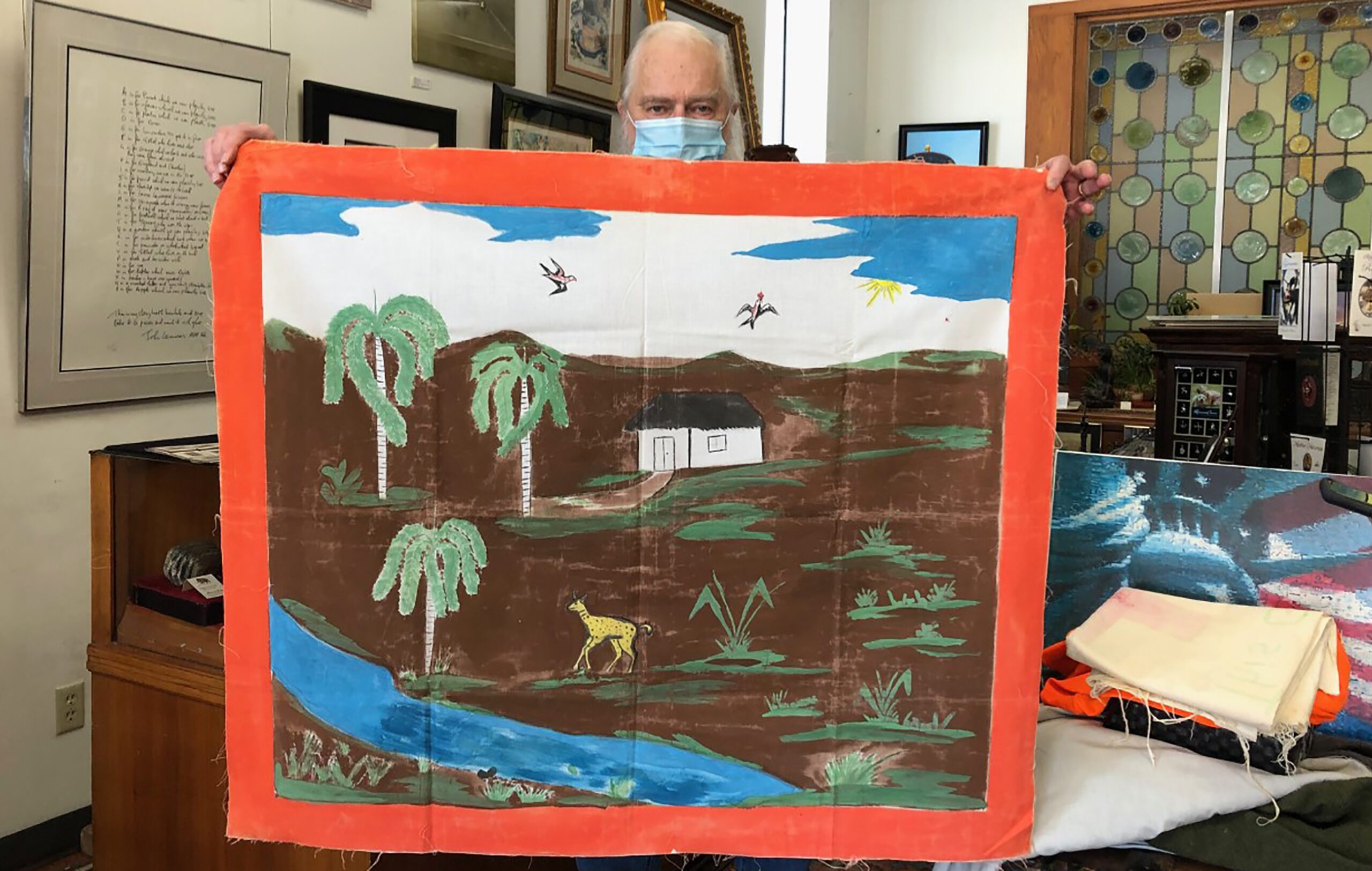

Satory has art created by the Mariel refugees — purses made from box straps and a hat made from cardboard. Some of these artifacts were featured on the TV show, “American Pickers.”

Satory would bring art supplies, like colored pencils and paint, to refugees he’d built relationships with through the dental clinic.

“A lot of times they would want to come to the clinic because there was a Coke machine there, they could talk to people and they had a little more freedom. Maybe get some candy or something else,” Satory said. “I would commission them. I would say, ‘Could you draw me a picture?’ or they might even have some pictures. So we would either trade or buy or commission for them to do it. It was always great colors, a lot of bright colors.”

Some of the most impressive pieces are the paintings that Cuban artists did on bedsheets.

Creating art that was critical of the government or depicted religious figures was a vehicle for refugees to process the trauma of displacement and cultural separation, Granados said. It was a way to openly criticize the government, something they weren’t able to freely express back in Cuba.

Black market and violence

A black market developed at the base — cigarettes, magazines, Cola-Cola cans, medical products, bedsheets, Army blankets, clothing — which the refugees could obtain from camp personnel by offering voluntary labor in camp maintenance tasks, or simply stealing from camp warehouses, Granados said. Cubans at the base could also receive money from relatives, which helped them purchase goods on the black market, as well as make collect calls from telephone cubicles that existed in each barrack area.

U.S authorities saw these activities as disruptive, but most of the time were not aware of them.

And that lack of awareness didn’t stop with the trading of goods.

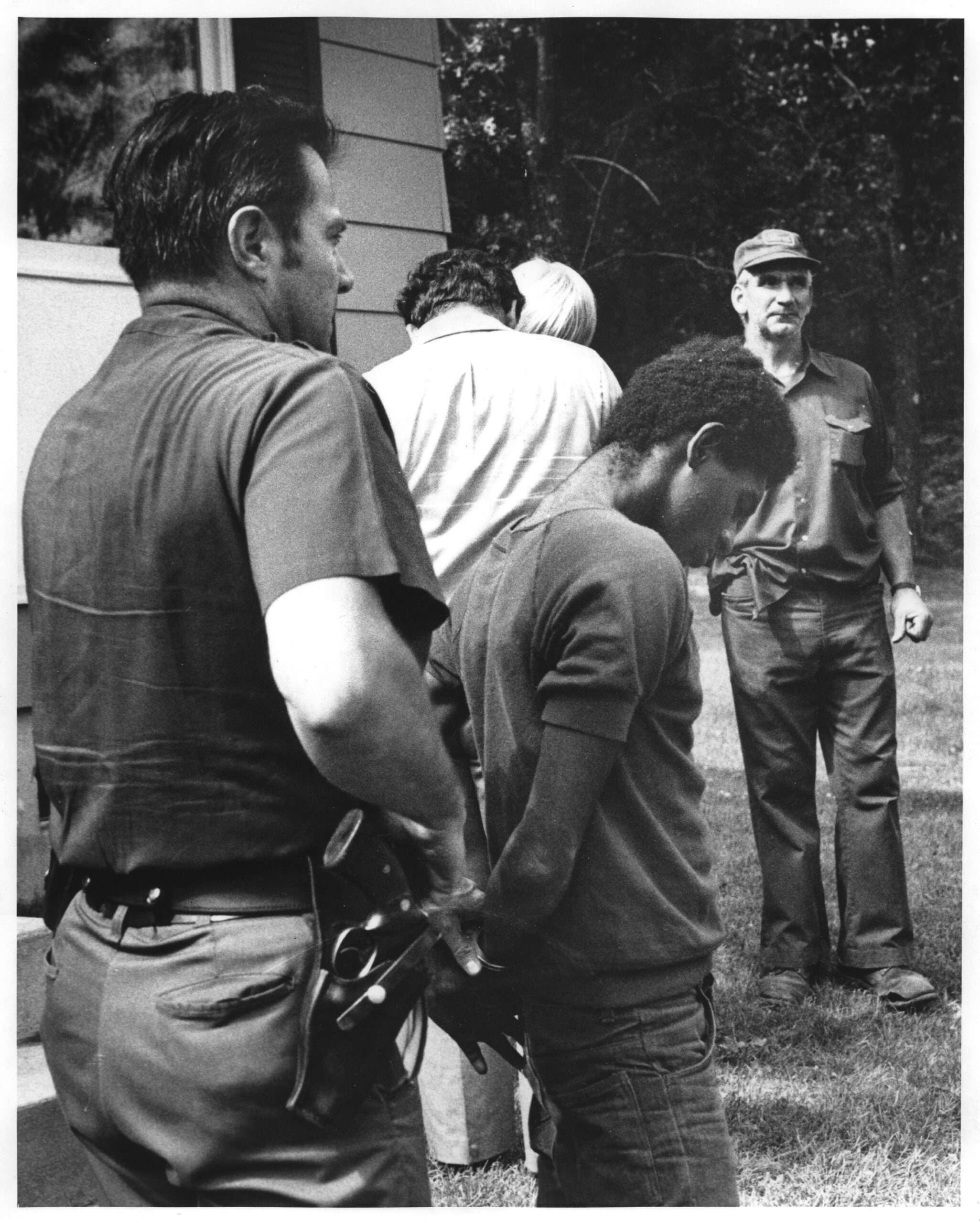

The refugees were on edge, to put it simply. They faced racism, homophobia and sexism in the camp, and some carried with them history between people who had been enemies in Cuban prison.

Fights were common among some refugees. There are letters from teenagers at Fort McCoy who feared for their safety because of the thefts, stabbings and sexual assaults.

And it wasn’t just the Cuban refugees committing crimes.

In a La Crosse Tribune articlefrom 1980, Fort McCoy commander Colonel William Moran said, “I was convinced and still am that an awful lot of things the Cubans got blamed for were not the Cubans.”

He went on to say that some exiles were involved in things like larceny and break-ins, but so were some of the 1,000 people he hired to work there.

Although only a small percentage of the refugees at Fort McCoy were dangerous, that group was wreaking havoc on camp life.

Satory remembers having to keep an eye on people as he rode the bus around the camp, making sure members of “gangs, or like almost like a mafia type thing” weren’t taking advantage of the vulnerable.

“If you didn’t keep track of who got on and who got off, they were forcing people to get off where they weren’t supposed to be. And they were like forcing women into prostitution and things like that,” he said.

Satory said it was a problem that sometimes kept him up at night.

“You’re worried about the people. There were a lot of problems there that were happening that you didn’t really want to see happen. And the government was also keeping some of those stories quiet. There would be a stabbing or something like that. You knew what happened, but it never got out,” Satory said. “I would be at the hospital and ambulances are coming in and unloading people and it’s like, ‘Nothing happened here.’”

Satory also said there were sometimes issues with the military police.

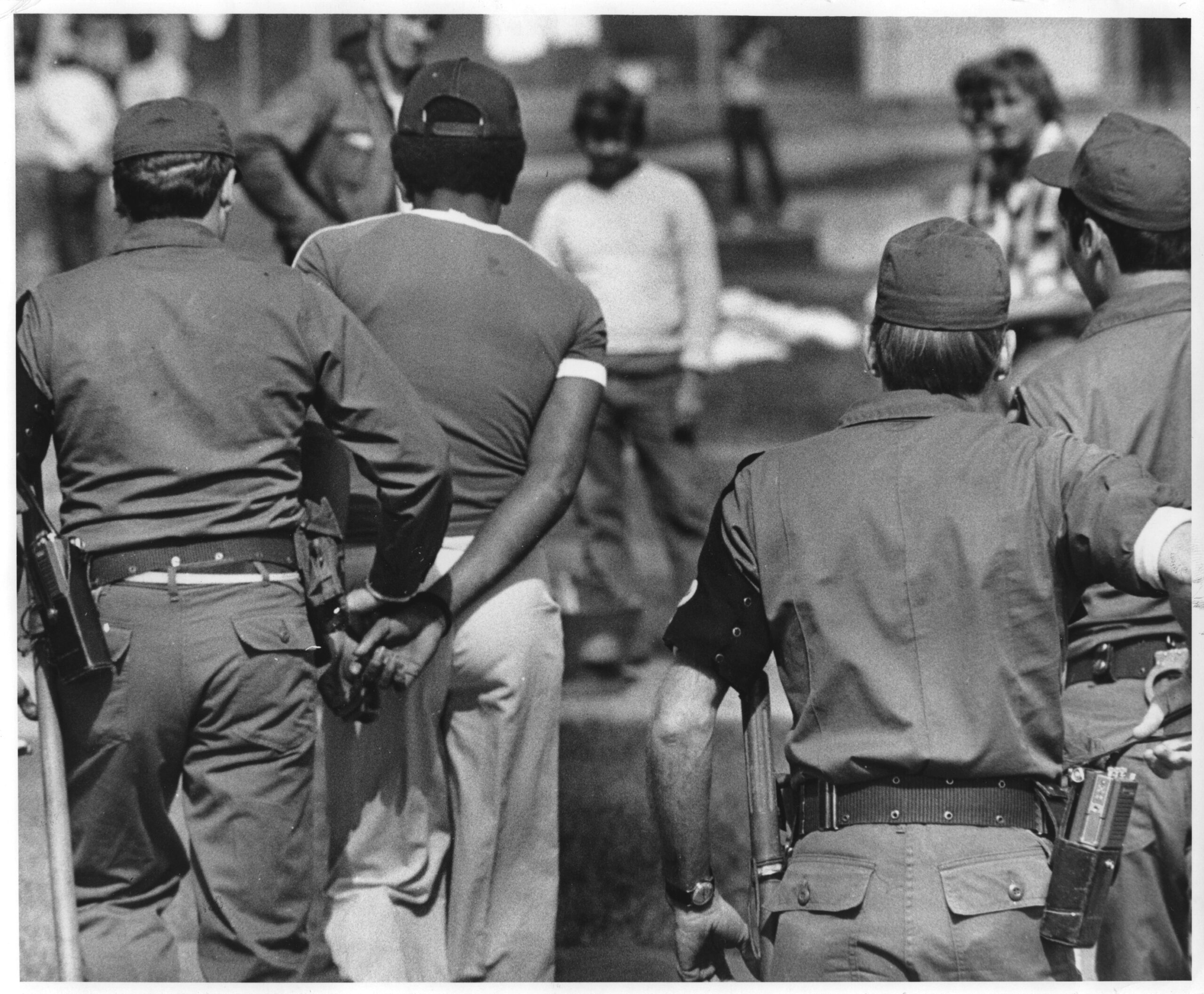

The military police had jurisdiction inside Fort McCoy. They were also in charge of the perimeter, so as refugees jumped the fence to escape, the military police, along with U.S. Marshals, would bring them back.

Armando Rodriguez was one of these refugees who tried to escape when he was 17 years old.

“We started getting crazy, like being there so long,” he said. “So I just crossed the fence, tried to leave, but they catch me. I went back and never tried no more.”

A 1980 editorial from the La Crosse Tribune mentions how some people faced harsh discipline if they were caught escaping. The article lays out abuses and mismanagement at the camp, reported by Detroit Free Press staff.

There’s also a story that made the local newspapers about two minors who escaped. It was part of a well-orchestrated plan to protect them from abuse inside the camp. A judge even intervened.

The situation grew so dire inside Fort McCoy, some people began hurting themselves.

Satory told a disturbing story of what he witnessed in the dental clinic: “We did have a problem with people taking pencils and pushing (them) up into their teeth — bleeding gums and all that. That was a chance to get out and maybe sell things or have soda pop or whatever.”

There were a number of motivations that people could have had for doing something like that, Granados said, particularly the minors escaping from a threat of internal gangs. Maybe they thought they would be sent to a hospital in town — they could have been involved in trading in the black market, so it could get them access to products. Granados added that a lot of people just wanted to get out of Fort McCoy.

FEMA and security

A number of federal agencies were running things at Fort McCoy, but it was the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, that was overseeing the entire resettlement operation across the country.

“Uprooted” reached out to FEMA with a number of questions, but the agency did not have anyone available for comment.

FEMA was only about a year old in 1980, and resettling the Mariel refugees was one of its first big missions. In some ways, the organization was still learning how to respond to emergencies and human migration crises, said Granados.

Federal officials are policing the situation inside Fort McCoy, but FEMA also started leaning on Cubans to police one another. That’s because FEMA and military police didn’t understand the cultural codes taking place or the dynamics that were brought from Cuba into Fort McCoy, Granados added. And there was a language barrier, so U.S. officials started relying on members of the Cuban Self-Governing Executive Committee to police the barracks, known as “los jefes.”

These jefes were referred to as Warhawks. That’s because they wore donated purple jackets with UW-Whitewater’s warhawk mascot on the back, according to Jillian Marie Jacklin, a lecturer at UW-Green Bay.

The jefes enjoyed certain flexibility moving through the camp areas and received extra supplies in lieu of payment, Granados said. They also worked to support orderly distribution of food and supplies and monitored cultural events and sports competitions.

More importantly, jefes would keep FEMA and camp officials informed about any escapes, rioting attempts or people suspected of being Cuban agents. They also worked closely with unaccompanied minors.

Jefes were allowed to carry weapons like knives or sticks, which contributed tosituations sometimes getting out of hand, said Granados. A report from the La Crosse Tribune in August 1980 says some jefes were accused of abusing minors.

People didn’t feel safe or protected by FEMA. They sometimes felt preyed upon by the jefes, and one another. They had to protect themselves. Some refugees took knives from the dining facility. Other people made their own.

Security forces were trying to curb violence on a day-to-day basis. But in the big picture, government officials were trying to avoid big riots that took place at other Cuban refugee resettlement centers, like the one at Fort Chaffee in Arkansas in early June 1980.

People there were growing frustrated with waiting to get out, so up to 3,000 Mariel refugees rioted, shouting “Libertad!” People set buildings on fire and jumped the fence surrounding Fort Chaffee. Police outside the base opened fire on those who left the camp. Dozens were injured.

While Fort McCoy didn’t have a riot on the same scale as Fort Chaffee, there were a few small ones. A two-day disturbance was the result of an unfounded rumor that Cuban refugees were being sold to sponsors. Another smaller riot took place as a group waited to be transferred to federal prison.Teenagers, who were frustrated with not being placed with foster families, also rioted after a trip to a bowling alley was canceled.

Media coverage

People outside of Fort McCoy read about some of these incidents inside the camp. Newspaper readers were kept up-to-date on the numbers of people arriving on any given day, read profiles on the refugees themselves as well as local resident reactions.

When Jacklin was getting her doctorate in history at UW-Madison, she published a paper examining media coverage of the Mariel refugees, specifically diving into local newspapers in La Crosse, Sparta and Tomah.

She wanted to see how people were talking about the refugees in the communities near Fort McCoy. She said many of the news articles focused on crime and how communities felt “unsafe.”

There was also a lot of reporting on fights inside Fort McCoy — people jumping the fence to get out, robberies and home break-ins in communities close to the base.

Some articles reported on threats aimed at the refugees.

“You’ll find articles that talk about, perhaps rather than shooting turkeys, shooting Cuban refugees to keep the area safer. Majorly racist, xenophobic sort of commentary by local residents about how much they didn’t want Fort McCoy to serve as a detention center. There is a lot of racial prejudice and also different levels of homophobia,” Jacklin said.

Local news stories not only looked at violence and crime, Jacklin found, they also looked at the refugees’ impact on the economy in the midst of a national recession. The typical immigration narrative “they’re taking our jobs” was circulating about the Cuban refugees, she said.

Jacklin also found there was very little reporting on perspectives from the Cuban refugees themselves.

“People (in journalism) will say, like, fair and balanced. That’s not very fair and balanced to only talk about criminality. Where are the voices of the refugees themselves? How can we tell positive stories?” she said.

This coverage was particularly problematic for Black Cubans, Granados said. Since many Black Cubans did not have family in the U.S., they needed sponsors to get out. And locals were becoming more nervous about sponsoring the remaining refugees, so it became more difficult to find people willing to take in the refugees.

Leaving Fort McCoy

As the resettlement efforts at Fort McCoy gained momentum, people started getting out. Some were reunited with family across the U.S. Others found local sponsors in Wisconsin — but then quickly left for bigger cities, like Chicago, or returned to south Florida.

But some people stayed in Wisconsin, like Rodosvaldo Pozo. He was sponsored in September 1980. One of the Fort McCoy kitchen workers paired him up with a family who lived nearby in Sparta. They were a young couple who had three kids.

Even though they don’t talk much today, Pozo said he still loves them.

“Where are the voices of the refugees themselves? How can we tell positive stories?”

Jillian Marie Jacklin

And then there was Ernesto Rodriguez. While spending his time in the kitchen at Fort McCoy, he met his sponsor family’s sons, Joe and Brian Brandstetter, Sparta residents who worked in the kitchen.

One day, a couple of refugees got in a knife fight in a kitchen and Joe was caught in the middle. Ernesto tried to stop the fight and ultimately pulled Joe from the middle of it, saving him. This solidified his friendship with the Brandstetter brothers and eventually led to Ernesto putting down his roots in the upper Midwest.

But not everyone at Fort McCoy found sponsors by the time the camp closed in fall 1980.

As winter approached, the government consolidated all the unsponsored adult Cuban refugees across the country into one camp: Fort Chaffee in Arkansas. This included about3,200 Cubans from Fort McCoy. The group was mostly single, Black men.

Osvaldo Durruthy was one of the Cubans who never found a sponsor in Wisconsin and was sent south.

On Nov. 3, 1980, the last Cuban refugees left Fort McCoy. That day, the 90 remaining unaccompanied minors were sent to live at Wyalusing State Park near Prairie du Chien.

Almost 15,000 Cubans passed through the gates of Fort McCoy in the summer and fall of 1980.

And just like that, they were gone.

On the next episode of “Uprooted,” the Cuban Wisconsinites get out of Fort McCoy and begin their new lives. They need to find jobs, learn a new language, and some of them start families.

Editor’s note: WPR’s Alyssa Allemand contributed to this report.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.