The mass exoduses that followed the Cuban Revolution

By: Maureen McCollum, Omar Granados

Episodio 3: traducción al español

Rodosvaldo Pozo was only a teenager when he was sent to prison in Camagüey, Cuba, after being accused of burning sugar cane fields. In the last episode of “Uprooted,” he wouldn’t say whether he really did it.

One day when Pozo was alone in his prison cell, he was approached with a question.

“So I was walking back and forth and (the) sergeant came in the cell and said, ‘Hey, Sr. Pozo, you want to go to the United States?’” Pozo said. “I told him, ‘Come on man, don’t play with me.’ He said, ‘Yes or no?’”

Pozo only had moments to decide whether to leave Cuban prison and head to the U.S.

“I said, ‘Well, if it’s true, yes.’ They told me, ‘Put your clothes on.’ And I went outside and there was a bus,” Pozo said. “They told me, ‘go.’ So I went inside, and I said, ‘Look at that. It’s for real what they’re doing.’ And from there, they take me to Mariel.”

As he left that Camagüey prison cell and boarded a mysterious bus at age 22, change was brewing hundreds of miles to the west at the Port of Mariel, Cuba.

In 1980, President Fidel Castro opened the country’s doors, allowing thousands of citizens to leave Cuba from the Port of Mariel for the U.S. every day.

After the revolution, it was hard for people to leave Cuba. It’s an island, and travel was a privilege reserved for the elite, like government officials, athletes and musicians.

So when Castro gave citizens an opportunity to leave, people did. There was a growing population of Cubans who weren’t happy with the state of things in their country, and it would lead to drastic attempts to get themselves and others out.

From April through October 1980, 125,000 Cubans left their homeland for the U.S. And 15,000 of these Cubans ended up in Wisconsin, including Pozo — who had been facing decades in prison.

Brewing discontent

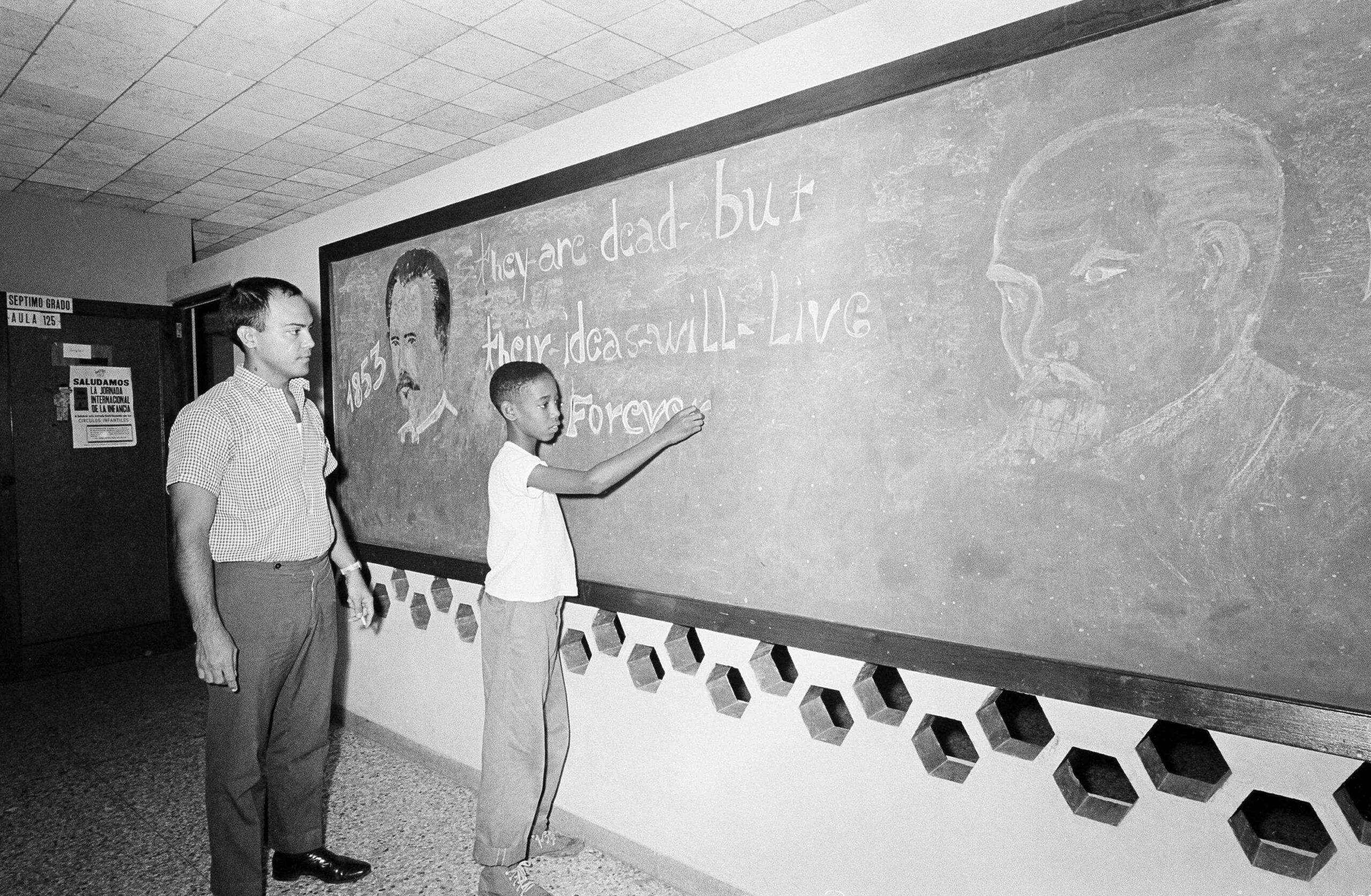

The Cuban revolution promised people a better life: free health care, schools and subsidized housing for everyone. And it was able to reach some of those goals.

Michael Bustamante is an associate professor of history and the Emilio Bacardí Moreau Chair in Cuban and Cuban-American Studies at the University of Miami and author of the book “Cuban Memory Wars Retrospective Politics in Revolution and Exile.”

Bustamante said that throughout the 1970s and 80s, socialism worked for most Cubans.

“Cubans who had been educated under the socialist system in the 60s and through the 70s began to sort of see the fruits of their labor. People of color, people from rural areas gained professional training and saw upward mobility,” Bustamante said. “There’s a fair amount of data to substantiate that.”

“But that doesn’t mean that there wasn’t frustration,” he added.

Even with the government providing new opportunities and free and subsidized food and housing, many still weren’t entirely satisfied. Consumer options for people were restricted. Goods were rationed and sometimes there were shortages. Some people turned to the black market or petty theft to get what they needed.

The black market in Cuba at that time included everyday goods like toilet paper, rice and children’s notebooks for school, said Omar Granados, an associate professor of Spanish and Latin American studies at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse and co-host of “Uprooted.”

“If you work at a hospital, you may steal aspirin from work and then sell it on the black market. And to the Cuban government, that’s people taking goods from the state — hurting the revolution,” he said.

Any type of economic crime that deviates from the economic success of socialism was dangerous to the state and its projects, Granados added. Economic crimes during that time were seen as more serious than violent crimes such as domestic violence.

With Cuba’s economy running 100 percent on state ownership, stealing goods was equivalent to stealing from the revolution.

This is what got Ernesto Rodriguez, who now lives in La Crosse, in trouble. He spent 11 months in prison for taking a bike after his dad’s funeral, and ended up returning to prison for another five years because he took food from a state-run store and sold it on the black market.

“If you want to survive in Cuba, you had to steal or you had to do business (on the) black market,” Rodriguez said. “Yeah, I was stealing — and I never steal from my friend’s house. I steal from the government because they’re the ones who have everything.”

In 1969, Castro announced the Revolutionary Offensive, which in part eliminated and criminalized economic exchanges that weren’t sanctioned by the government. Lillian Guerra, an author and professor of Cuban and Caribbean history at the University of Florida, said the change was significant.

“That means that you cannot paint somebody’s nails in your house or what used to be your own little nail salon, because the nail salon has been nationalized. It’s now a criminal offense that carries a great deal of weight for painting somebody’s nails in your house and charging the money for it,” Guerra explained. “Even bartering one service for another is a criminal act, because if you’re going to be building communism, the government has to control all forms of economic exchanges.”

“Anything that inhibits government control of economic exchanges — whether they’re trade or they’re bartering of one good for another — anything that does that will limit the ability of the state to march forward towards this perfect communist utopia in which we’ll have total egalitarianism,” she continued.

One way the state controlled the culture and the economy was by having eyes on the ground.

“Everywhere across the island, people are persecuted and prosecuted,” Guerra said. “That means their neighbors are denouncing them to the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution or to the local police for doing things that they’ve done for generations.”

People in Cuba were pressured into hard labor and voluntary work for the revolution, Granados said, like construction for a new hospital or picking potatoes. Anyone who started an enterprise that was not owned by the Cuban government was considered an enemy against the system, Guerra said. And if someone committed a crime, that work could become more strenuous.

“Men — largely men — would be caught doing something illegal, as minimal as selling cigarettes — selling rations that people don’t use. There was a cigarette ration. If you don’t smoke, what do you do with your cigarettes? You committed this economic crime. So now you have to go do backbreaking labor for the state, for a minimum wage because you’re not a revolutionary. That would then further deepen their alienation and their distance from the state,” Guerra explained.

Then, people just stopped showing up for work, according to Granados.

In the early 1970s, a new law was created, Guerra said, one that was essentially against laziness. It was applied to people who refused to go along with Cuba’s government-owned economy.

People like Pozo, who said he didn’t want to cut sugar cane for communists.

“Everywhere across the island, people are persecuted and prosecuted.”

Lillian Guerra, author and professor of Cuban and Caribbean history at the University of Florida.

The Sovietization of Cuba’s economy and culture

Throughout the 1970s, Cuba was becoming more dependent on the Soviet Union for food, staple goods and appliances — not to mention billions of dollars in aid that were dedicated to social services, according to Granados. This was in the midst of a trade embargo with the U.S.

Many state-run businesses of the revolutionary government were modeled off the Soviet Union and the socialist Eastern Bloc, Granados said. This included how the economy functioned and strict censorship rules.

There was also a Sovietization of culture, Granados said. He grew up in Havana, Cuba, and said he remembers “a child playing chess, watching Russian cartoons and going to the ballad to see Russian ballerinas that I would never even dream of seeing now, as an adult.”

Guerra explained why the Cuban government would want to limit the type of culture or entertainment that its residents had access to: “You cannot have economic, ideological or cultural autonomy from the state as a citizen. If you do that, you threaten the state. So the logic is that you have to have a state control the press and the state has to control the economy. And it should control the culture.”

But despite the government limiting culture, music and books, many Cubans remained connected to Western and American culture, Granados said. For example, some people in Cuba still found ways to listen to music by The Beatles, though the band’s music was banned for a time on Cuban radio, according to the Associated Press.

Granados said his first experience hearing The Beatles was in the 1990s.

“I went to a big celebration that they were having in a public park in Havana to unveil a statue of John Lennon. I didn’t even know that much about John Lennon at the time,” Granados recalled. “I had gone to the event to see my favorite singer, Silvio Rodríguez, who was playing a song by John Lennon, only to find out that Fidel Castro himself was unveiling the statue. And this was the year 2000.”

This is an example of the connection to Western and American culture Cubans have always had. And it wasn’t just with music, but with literature and material goods.

These government-imposed limitations were among the reasons some Cubans wanted to leave the island.

“You have to have a state control the press and the state has to control the economy. And it should control the culture.”

Guerra said.

Migrations: From the Golden Exile to Mariel

The path was narrow for people to leave Cuba after the revolution, but there were moments when people could emigrate from the country. It started with the Golden Exile.

The Golden Exile was the first major emigration after the Cuban Revolution, lasting from 1959 until 1962. It was mostly middle and upper class, white Cubans who were supporters of ex-president Fulgencio Batista, or people who quickly decided they did not want to be a part of revolutionary Cuba.

In 1965, the Camarioca Boatlift took place. Castro said Cubans with relatives in the U.S could leave the island. Nearly 3,000 people boarded boats and moved to the U.S. Castro viewed this situation as a way to get rid of those who were not buying into the revolution.

The Freedom Flights occurred from 1965 to 1973. During this time, Cubans had an opportunity to emigrate to the U.S., hopping on flights from Havana to Miami, Florida. Once they arrived in the U.S., they were eligible to work and receive a green card after a year through the Cuban Adjustment Act of 1966.

Las visitas de la comunidad

In 1979, Bustamante, with University of Miami, said Cuban Americans were given an opportunity to visit their homeland through las visitas de la comunidad, or “the visits of the community.”

For the first time in years, the Cubans who had left after the revolution — and built new lives and accumulated wealth in places like Miami and New Jersey, which is the second largest Cuban-American settlement in the U.S. — were eager to go back to Cuba to visit their homes and families, Granados said.

Bustamante said calling the trips “community visits” was a big change in perception.

“It was sort of this new euphemism to refer to those who had left the country. Prior to the late 1970s, (those people) had been really referred to in Cuba by a lot more insulting terms — worms, apátridas, literally people without a country,” Bustamante said. “The decision to leave the island in the 60s and early 70s was tantamount to national betrayal as far as Cuban revolutionaries were concerned. So, the change in the lexicon to suddenly calling these folks ‘the community’ but also not calling them exiles — which is how most identified themselves — I think is significant.”

Bustamante, who’s an expert on las visitas de la comunidad, said up to this point, Cuban Americans who left after the revolution didn’t have a way to return home. So these visits were a big deal.

“Over the course of a year, 100,000 Cuban exiles, Cuban Americans, go back to their home country that some haven’t seen in the better part of 20 years. People are going back to see a country that they had left behind. Going back to reconnect with family that perhaps they had been able to keep in touch with. Perhaps they hadn’t been. It’s really sort of a clash of cultures and a clash of two worlds,” Bustamante said.

And the Cuban American visitors brought a lot of stuff with them to the island — gifts like appliances and clothes. Bustamante said this was eye-opening for the Cubans receiving the gifts, since it contradicted an image of what life was like for working class people living in a capitalist Western society.

“There are contemporaneous interviews with some Mariel refugees who when they’re asked, ‘Why did you come?’ Some will point to the fact that, ‘My opinion changed about my country when my aunt came back to visit and brought me stuff and told me these stories about what life was like in the United States,’” Bustamante said.

Granados gave some examples of this “stuff” he witnessed when growing up in Cuba: “So if you went to school, for example, or you were playing with your friends and somebody had a Walkman or a video game, it was mind-blowing, you know, that that person either had family in the United States or was the son or daughter of a famous musician or athlete that could travel, perhaps a diplomat.”

But people weren’t dreaming about leaving Cuba just because of stuff. Some had been mesmerized by the idea of the American Dream for decades, said Granados.

Plus, Bustamante argued that Cubans saw people coming and going freely during las visitas de la comunidad in 1979, and that left a mark on them.

“Cubans have grown up hearing that those who left are the enemies of the revolution,” Bustamante said. “Then all of a sudden, 100,000 people come back who you have been told — in school, in your workplace or in the media — are the enemies of the revolution. And they come back and they’re welcomed, to a certain degree, and they’re bringing all this stuff. Then, they can get on a plane and go back. So I think that was probably a shock to the system for Cubans.”

Las visitas de la comunidad were just one of many events that led to the Mariel Boatlift in 1980.

There were many Cubans who were already dissatisfied with the state of their lives and their country. They saw people they know living in a very different world than the one they lived in. And they couldn’t unsee it.

Then, in April 1980, it all came to a head.

An interactive timeline by Amanda Moreno. Cuban Heritage Collection, University of Miami Libraries, Coral Gables, Florida

A breach at the Peruvian embassy

On March 8, 1980, Fidel Castro gave a speech mentioning the 1965 Camarioca Boatlift.

The boatlift was a catalyst for the Freedom Flights, and Castro said in the speech these kinds of movements were necessary “to get rid of the non-revolutionaries, the people who just will not be swayed, the people who are doubters, the anti-socialists, the anti-socials, those who are immune to political…indoctrination,” Guerra said.

Napoleon Vilaboa, a Cuban spy who lived in Florida, allegedly gave Castro the idea to orchestrate another boatlift in 1980. The “Father of the Freedom Flotilla” was even prominent on Miami radio waves, encouraging people to pick up their relatives. According to Mirta Ojito, author of “Finding Manana: A Memoir of a Cuban Exodus,” the Cuban government initially thought only 22,000 Cubans would leave for the U.S. Instead, almost 125,000 left.

“I don’t think that this high political elite had any clue the degree of discontentment there was: the anger, the outrage, the — what I would think is a major causative factor — political exhaustion on the part of young people and anger over their inability to express that anywhere,” Guerra said.

On April 1, 1980, less than a month after Castro gave that speech, six people rammed a bus through the gates of the Peruvian embassy in Havana. It was one of many embassy breaches that occurred in Cuba that year. These people were seeking asylum from the Peruvian government, thinking it was their only way out of Cuba.

After the breach, Cuban guards opened fire and one guard was killed in the aftermath.

On April 4, 1980, the Peruvian government granted the six Cubans asylum.

The next day, Castro removed the embassy’s military protection.

“Fidel, in retribution for the death of the guard and the unwillingness of the Peruvian ambassador to return these folks, takes away the Cuban guards,” said Guerra. “Literally within minutes, according to Ambassador Ernesto Pinto Bazurco, a Black Cuban man walks through the gates. (Pinto Bazurco) was astounded because one of the pillars, supposed pillars, of revolutionary support was Black people.”

Within 24 hours, more than 10,000 people walked through the gates of the Peruvian embassy. They quickly packed into an area that was roughly the size of a football field.

The Cuban government had to act fast. The embassy breach was quickly turning into a humanitarian crisis, since people didn’t bring food or water.

Latin American countries began stepping in, saying they would welcome some refugees.

On April 14, 1980, American President Jimmy Carter’s administration announced the U.S. would take in 3,500 of the Peruvian embassy’s asylum seekers as part of the Refugee Act of 1980. Around this time, there was some optimism within the Carter administration that the relationship between the U.S. and Cuba could improve.

On April 20, 1980, Castro opened the doors to his country and told exiles in the U.S. that they could pick up their relatives at the Port of Mariel.

The Mariel Boatlift

At the Port of Mariel, a flotilla emerged quickly. Hundreds of boats arrived at the shores of Mariel to pick people up. Thousands of people began leaving Cuba every day.

By October 1980, a total of 124,776 Cubans had emigrated from Cuba to the U.S.

What started as a way to get anti-government sentiment out of the country had become a mass exodus.

But even so, the Cuban government used this moment to send some people it viewed as troublemakers away, including those in psychiatric hospitals and prisons.

Ernesto Rodriguez and Rodosvaldo Pozo were both in prison as the boatlift got underway.

Pozo was in Kilo 7 prison for allegedly burning sugar cane fields at this time. Suddenly, he was given a choice to leave Cuba for the U.S. He told his family he was leaving.

“Well, you know, you always think about your family, especially when you live with your mama,” Pozo said. “In Cuba, I had to do 26 years for something they accused of me, they never (saw) me doing it, you know? My mama (came) and see me in May. And she told me, ‘I heard (a) rumor that people going to the United States, are you leaving?’ I told my mom no, but my brother was with (her). My mom went to the bathroom and I told my brother, ‘Man I got to leave. I don’t got no choice.’ And then I told l my mom.’”

Pozo felt like he had to go. Otherwise, he’d be stuck in prison under the communist government, which he did not agree with.

Rodriguez was in prison — for the second time — for taking food from a state-run store to sell on the black market.

“I was in prison when I heard there were 200 boats in Mariel,” Rodriguez said. “I hear Castro was opening the door because Jimmy Carter said, ‘You can send those people, the family can come.’”

Rodriguez didn’t have family in the U.S.

“But Fidel say, ‘OK, you want everybody? OK.’ He take a lot of people from prison — crazy people, murder people — to America,” he said.

When prison officials asked Rodriguez if he wanted to leave Cuba for the U.S., he had to make a split-second decision on whether to go.

“I go, because I don’t want to be (in prison) for 40 years,” Rodriguez said.

He said he was then sent to another cell for two days and transferred to a small room, where he slept on the floor for two weeks while waiting to board a boat.

After deciding to leave Cuba — to leave their families, their friends, the only home they’d ever known — the time came for the exiles to make their way to the Port of Mariel.

But Rodriguez said on the bus journey to the port, he didn’t receive a fond farewell from his fellow Cubans.

“Before we get in Havana, people was throwing rocks and eggs, (shouting), ‘Get out! You don’t like the government, get out of here! We don’t want you here!’” Rodriguez remembered.

Just as it had done in the past, Castro’s propaganda machine was disparaging the people that wanted to leave Mariel, calling them scum or escoria or undesirables.

Lillian Guerra said the Committees of the Defense of the Revolution had a 100,000-person meeting that sparked mob-type rallies that could last days to weeks.

“They would surround your home and they would spray paint the front of your house with government-supplied spray paint and they (wrote) ‘traitor.’ They’d write ‘gusano,’ which means worm. They’d write homosexual, antisocial, lumpin, and they’d throw eggs at it,” she said.

“They chant for hours. Sometimes they cut off your electricity and your water. They would terrify you and that would be the case until you were actually allowed to leave. So the depth of the traumas associated with the Mariel Boatlift go far back,” Guerra added.

For the Cubans who decided to leave, this was their goodbye to the only home they’d known.

Once the exiles made it to the Port of Mariel, people like Rodriguez and Pozo saw hundreds of boats waiting to take them across the Florida Straits to the U.S.

“I stayed there one night,” Rodriguez recalled. “The next morning about 8 a.m., they put me in the line and say, ‘You see the boat over there, get in it.’”

They had no idea what they were in for.

In the next episode of “Uprooted,” the Cubans experience a treacherous boat ride. They eventually land in Florida, where their welcome to the U.S. isn’t much better than their farewell in Cuba.

Editor’s note: WPR’s Alyssa Allemand contributed to this report.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.